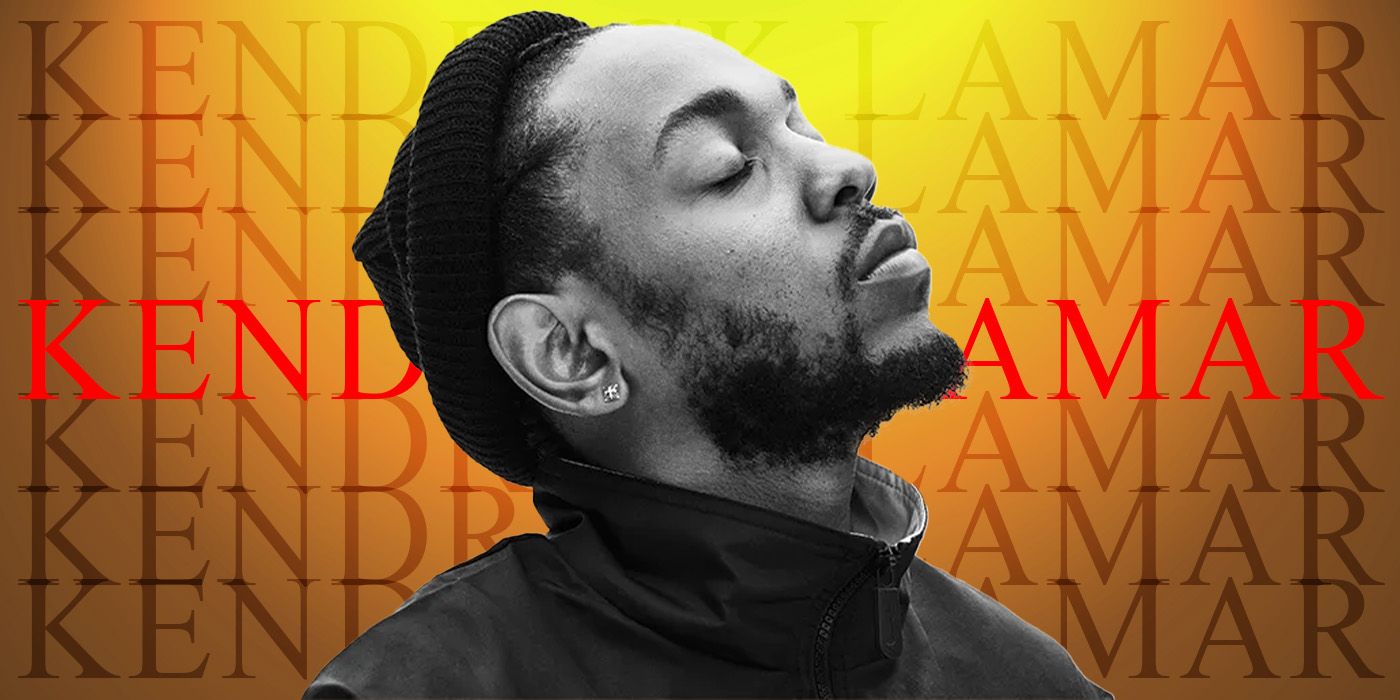

Rap is the perfect playground for wordplay, metaphor and airing one’s beefs. Few rappers weave these elements into their work better than Kendrick Lamar. The Compton rapper has had an incredible year, which started with his performance at the Superbowl halftime show. The performance, which featured his now famous diss track “Not Like Us,” was a great opportunity for Lamar to show off his flawless catalog to the world and flex his writing and performance skills.

As an artist, Lamar is multi-talented and among his fans he’s famous for weaving deeper meaning, historical context and personal struggle into his music. All of these factors are present in this list, which includes some of the rapper’s best and most complex lyrics.

10

“Everybody gon’ respect the shooter / But the one in front of the gun lives forever.”

“Money Trees” (2012)

Martyrdom is laid bare in only a few words on Kendrick Lamar’s “Money Trees”. The meaning behind the lyrics is quite straightforward, but in a cultural climate dominated by police violence, the emphasis on the eternal life one gains when they become a victim is more resonant than ever.

Among the benefits of carrying out a gang-affiliated murder is the clout and status gained within one’s community. The irony in this scenario is that the unwilling participant is the one who gains the most status. Conversely, the person seeking validation will always be second place to the victim.

9

“Hereditary, uh, all of my cousins, uh / Dyin’ of thirst, uh, dyin’ of thirst, uh, dyin’ of thirst, uh”

“Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst” (2012)

“Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst” is as multilayered and story-oriented as one would expect from Lamar’s work. Throughout the song, Lamar ruminates on the idea of being forgotten and yearning for his voice, and the voices of the characters he is speaking through, to be heard. Referencing heritability in this sense evokes the cyclical nature of struggle for Lamar, his family and community.

Lamar isn’t isolated in his struggles or ideology. His upbringing, environment and community all contributed, and thus, the people around him yearn for the same recognition and sense of fulfillment. Lamar’s empathy for those around him has always been a key hallmark of his work. It’s clear from his lyrics that the pressure of representing his community isn’t taken lightly, and that, despite where he has ended up, he certainly hasn’t forgotten where he came from.

8

“No, you not a colleague, you a f*****’ colonizer”

“Not Like Us” (2024)

Cultural appropriation is obviously a hot button topic that brings out a lot of strong opinions and it’s one of many elements mentioned in “Not Like Us.” Cultural appropriation is not as simple as a person taking on a trait or aesthetic that was originated by another culture. The additional layer that many people often overlook is that the trait or aesthetic being imitated is usually something the originating culture is shamed and degraded for. When an outsider garners praise for something others are shamed for, it highlights the obvious prejudice that the originating culture faces.

The culture of rap as it’s known today owes a lot to lower-income Black communities. For many rappers, their upbringings were challenging, and participating in crime or gang activity was a necessity to survive in their own communities. These circumstances resulted in negative stereotypes associated with criminality for many. So, when Drake moves through the rap scene as if he is a peer to those around him, the former child-star gives the impression that he is encroaching on territory that does not belong to him and attempting to dominate it.

7

“King Kunta, everybody wanna cut the legs off him”

“King Kunta” (2015)

Lamar’s 2015 track “King Kunta” references the character Kunta Kinte from the groundbreaking TV miniseries Roots. In the miniseries, Kunta (LeVar Burton) refuses to take on a slave name and is punished mercilessly for it. Kunta’s moral purity and refusal to forfeit his identity to slavers elevates him as a king in the eyes of Lamar.

The ironic dichotomy of “King Kunta” as a title is, of course, that within the narrative of Roots, Kunta was on the lowest possible rung of the social hierarchy. Labeling him a King cuts a striking contrast with his status. When comparing himself to Kunta, Lamar reaffirms that he is confident about being true to himself and his community. And although it may make him morally superior, it also makes him a target for people who want to knock him down a peg or two.

6

“And that goes for Jermaine Cole, Big K.R.I.T., Wale / Pusha T, Meek Millz, A$AP Rocky, Drake / Big Sean, Jay Electron’, Tyler, Mac Miller”

“Control” by Big Sean (2013)

Kendrick Lamar’s feature verse on “Control” may be better known as the verse that launched a thousand rap beefs. The lyrics don’t necessarily have a deeper or hidden meaning, but casual listeners of Lamar’s work may not be aware of how utterly gargantuan the impact of this verse was on the rap industry when it was released.

Not many of the other artists mentioned in the verse made direct and immediate replies. The most responses to the verse came from a range of New York rappers who took issue with Lamar calling himself the “King of New York” on the verse. The New York line was a direct quote from one of Lamar’s idols, Kurupt, which flew directly over the heads of the East Coast rappers who replied to “Control “despite not having earned themselves a mention. Meanwhile, others were flattered by the mention, as it implies they are at the top of their game and are competing with the best. Artist Flying Lotus said it best: “Anyone who felt they needed to write a response to Kendrick’s ‘Control’ verse already lost.”

5

“You killed my cousin back in ’94, f*** yo’ truce”

“m.A.A.d city” (2012)

In 1992, in response to the execution of Henry Peco by the LAPD, the Bloods and the Crips agreed on a truce. It was an unprecedented moment in gang culture and is credited as a factor in the reduction of area crime rates in the 90s and 2000s. On the track “m.A.A.d city“, Lamar refers to the truce, and, while performing in character, suggests he would disregard it in the name of personal revenge.

This is a clear reference to the truce between the two gangs. But it is also a reference to the smaller interpersonal challenges that can cause something as monumental as a gang truce to crumble. Oftentimes, for a truce to succeed, both parties need to be the bigger person and let things go in the name of the greater good. But for many individuals, that is a near impossible task. In the narrative that Lamar is forging through this lyric, he is referencing how a personal beef, for example, a cousin being killed by a rival gang, can topple years of peace.

4

“F*** who you know—where you from, my n****?”

“m.A.A.d city” (2012)

Communities within low socioeconomic areas are typically fiercely loyal, and operate within their own sets of rules, ethics, and standards. For anyone even remotely versed in the history of segregation and oppression of Black people in America, the reason for this is obvious. These communities are mistreated, left behind, underfunded, and as a result, they must rely on each other to thrive.

All of this historical context comes into play when Lamar says, “F*** who you know—where you from.” The idea of mutual connections or good reputation means nothing in the grand scheme of things. When push comes to shove, the most important thing for Lamar and people within his community is where you came from and what that tells others about who you are and what you stand for.

3

“AK’s, AR’s, “Ayy, y’all, duck” / That’s what mama said when we was eatin’ that free lunch”

“m.A.A.d city” (2012)

Lamar’s wit, love of innuendo and ability to combine these factors with an evocative and emotive message are all on full display in these lines on “m.A.A.d city“. Lamar talks about gun violence, and references semi-automatic weapons, like AK47s and AR15s. He then transitions to the alliterative statement “Ayy, y’all, duck”.

The wordplay is smart and witty. But after the quick chuckle, Lamar brings listeners crashing back down to earth when he reveals that discussions of guns and outbreaks of gunfire were things that his own mother had to tell him when the family was eating at a government-funded free lunch program. The lyric is the whole package, representing Lamar’s humor, sharp use of innuendo and honest representations of life amid gang violence.

2

“What you want you? A house or a car? / Forty acres and a mule, a piano, a guitar? / Anythin’, see, my name is Uncle Sam, I’m your dog”

“Wesley’s Theory” (2015)

The 2015 track “Wesley’s Theory” explores the pitfalls of the ways in which Black Americans are encouraged to participate in American consumerism. Throughout the track, Lamar muses about the way the country is happy to treat minority groups poorly while still accepting their tax dollars. The song’s title, “Wesley’s Theory“, is likely a reference to Wesley Snipes, the actor and star of Blade who was imprisoned for tax evasion.

It is a colloquially known truth that many wealthy people evade taxes and participate in white collar crime. For that reason, it seems obvious to many why Black actor Wesley Snipes is one of the few high-profile people who have actually been convicted of tax evasion. Throughout “Wesley’s Theory“, Lamar circles around the idea that, for black Americans, capitalism and the pursuit of wealth and material goods is a sheep in wolf’s clothing. Despite being bolstered as a part of the American dream, taxation and economic investment don’t yield the same benefits for Black Americans as they do for other groups.

1

“It’s nasty when you set us up then roll the dice, then bet us up / You overnight the big rifles, then tell Fox to be scared of us”

“XXX.” (2017)

This lyric on “XXX.” shares DNA with messaging of “Wesley’s Theory“. Large institutions, from government to news outlets like Fox News, are quick to portray minority groups, gangs and people in poorer communities as dangerous enemies. These groups simultaneously do little to keep guns out of people’s hands, and often contribute to many of the factors that negatively impact minority groups and lower socio-economic communities.

This same idea is explored in “Wesley’s Theory” and in much of Lamar’s other work. A history of segregation, economic discrimination and prejudice has disadvantaged Black Americans. Arguably, government and mainstream media put little effort into remedying these long-standing injustices. In this narrative, Black Americans are set up to fail, and when they do, they are villainized, imprisoned for profit and further disadvantaged.

Discover more from imd369

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.