January 02, 2026

5 min read

A 29-year-old woman was referred to Tufts Medical Center for undifferentiated bilateral anterior and intermediate uveitis.

The patient first presented to an outside ophthalmologist with an irregular-appearing pupil and floaters beginning more than a year prior. She was diagnosed with bilateral anterior uveitis. Treatment with topical prednisolone acetate improved the intraocular inflammation, but it would recur immediately following steroid taper. She remained on topical prednisolone twice daily as maintenance therapy.

Overall, she had no notable autoimmune or infectious history. On review of systems, she endorsed diarrhea more than four times a day, which led to 10 pounds of unintentional weight loss over the past 6 months. She denied back pain, joint pain, oral or genital ulcers, shortness of breath, new rashes or urinary changes. She owned a cat and had traveled to Europe within the past year. She had tattoos without acute changes at the initial presentation.

Workup for tuberculosis, syphilis, Lyme, Bartonella and HLA-B27 was negative. Angiotensin-converting enzyme was within normal limits. Due to later development of bilateral vitreous cell and cystoid macular edema of the right eye, the patient was referred to our uveitis clinic for further evaluation. (The patient gave verbal consent for this article.)

Examination

Best corrected vision was 20/20 in both eyes. IOP was 20 mm Hg in the right eye and 18 mm Hg in the left eye by applanation. Pupil exam, confrontation visual fields and extraocular movements were normal bilaterally. Anterior segment exam was notable for rare cell in the right eye and trace cell in the left eye. There were no keratic precipitates or posterior synechiae present. A dilated fundus exam revealed trace anterior cells in both eyes. No haze, snowballs, snowbanks, or signs of retinal vasculitis or choroiditis were present.

Imaging

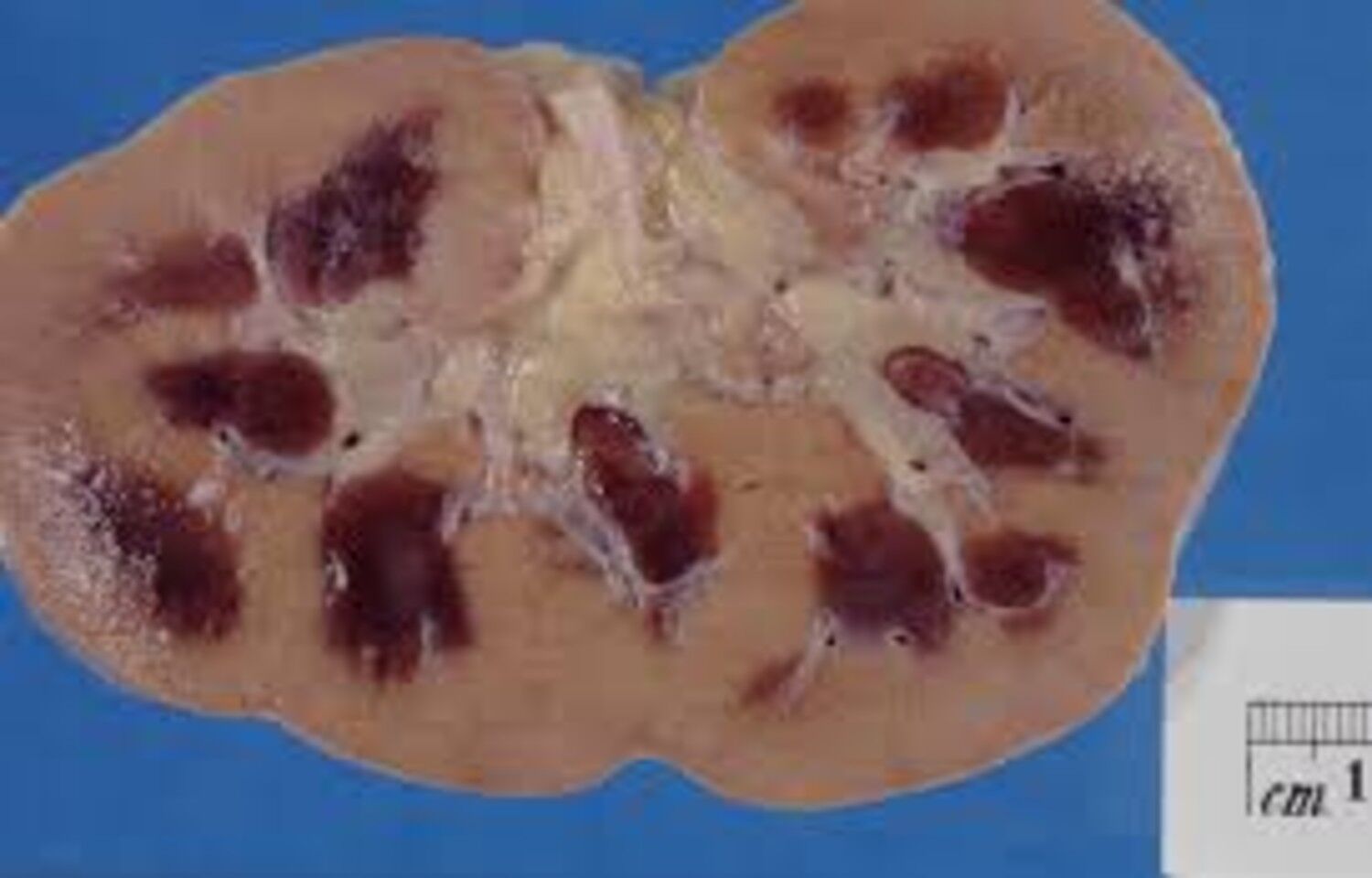

OCT of the macula showed no cystoid macular edema with normal retinal architecture. Fluorescein angiography showed bilateral nonspecific peripheral leakage. Patchy areas of delayed choroidal filling were present in the left eye (Figure 1).

Source: Ke Zeng, MD, and Lianna Valdes, MD

What is your diagnosis?

See answer below.

Undifferentiated bilateral uveitis

The differential for bilateral anterior and intermediate uveitis with retinal vasculitis remained broad for infectious, autoimmune, neoplastic and idiopathic etiologies.

While the preliminary infectious workup that included tuberculosis, syphilis and Lyme was negative, Whipple disease was considered due to uveitis and recent diarrhea with weight loss. However, the patient did not present with polyarthritis and central nervous system effects, which are commonly associated with Whipple disease. Inflammatory causes such as inflammatory bowel disease related to HLA-B27 remained on the differential. Further workup was pursued with gastroenterology.

Other inflammatory causes to rule out were sarcoidosis and tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome — a worthwhile consideration for bilateral anterior uveitis in a younger female patient. Tattoo-associated uveitis was also considered but deemed less likely without tattoo swelling. Neoplastic etiology such as lymphoma was deemed less likely due to the patient being younger and immunocompetent. Notably, up to 50% of uveitis cases are idiopathic, so this was a consideration as well (Maghsoudlou et al.).

Workup and management

Repeat testing for syphilis via treponemal antibodies was negative. Additional lab tests for rheumatoid factor, ANA and Whipple PCR all returned negative. Beta-2 microglobulin, which is elevated in TINU, returned normal. Lysozyme was within normal limits, and a chest X-ray showed no signs of sarcoidosis. Both P-ANCA and C-ANCA were negative.

Gastroenterology workup for infectious causes of diarrhea returned negative. However, there was elevated fecal calprotectin, a nonspecific indicator for stool inflammation, at 220 µg/g (normal 0-120). Biopsies from upper endoscopy and colonoscopy revealed lymphocytosis with preserved intestinal architecture. With an HLA-DQ2 haplotype and elevated levels of deaminated gliadin IgG as well as transglutaminase IgG and IgA, the patient was diagnosed with celiac disease. She subsequently converted to a gluten-free diet.

During the systemic workup, the patient returned with worsening uveitis symptoms. Treatment was switched from topical prednisolone to difluprednate, and an oral prednisone taper was started. One month into the taper, she reported all her tattoos gradually became indurated, swollen and painful (Figure 2). Her intraocular inflammation similarly worsened during this period. The presence of concurrent tattoo inflammation and uveitis led to a presumed diagnosis of tattoo-associated uveitis.

Discussion

Tattoo-associated uveitis is the presence of cutaneous inflammation of tattoos with concurrent intraocular inflammation. Due to a similar granulomatous inflammatory process, differentiating it from sarcoidosis can often be challenging (Ghalibafan et al.). Appropriate lab testing and imaging workup should be first pursued, as tattoo-associated uveitis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Some have theorized whether tattoo-associated uveitis is sarcoidosis localized to the skin and eyes; others have postulated a delayed-hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink (Carvajal Bedoya et al.).

Similar to our case, patients most commonly present with bilateral anterior uveitis. Vitritis and cystoid macular edema are also common findings. Larger tattoos and black ink have been more commonly implicated. A recent systematic review found 89% of patients have skin inflammation that preceded or coincided with ocular inflammation. Symptom onset has been reported to occur between days to years after tattooing (Ghalibafan et al.).

Inflammation is often controlled via steroids or immunosuppression. Although uncommon, excisional removal of small tattoos has demonstrated complete inflammatory resolution in reported cases (Carvajal Bedoya et al.). Laser tattoo removal is generally not recommended due to greater immune system exposure to pigment leading to concern for amplifying the inflammatory response (Izikson et al.).

While tattoo-associated uveitis has been documented in literature as an overall rare entity, incidence is postulated to be rising due to a dramatic increase in tattoo prevalence. In the United States, tattoo prevalence has doubled in 20 years, with around 30% of adults having at least one. We believe inquiring about tattoos is a valuable review of systems question when working up a patient with uveitis, especially a bilateral case.

Celiac disease is often not on the differential for causes of uveitis. Albeit rare, several cases of noninfectious uveitis have been attributed to celiac disease (Krifa et al.; Saleem et al.). A few larger-scale studies have also suggested patients with biopsy-proven celiac disease have an increased risk for developing uveitis (Boustany et al.; Mollazadegan et al.). This remains an area for further investigation.

Tattoo-associated uveitis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Due to concurrent celiac disease, which is a possible cause for uveitis, we are unable to definitively diagnose the patient with tattoo-associated uveitis. However, tattoo association with uveitis is more convincing because her uveitis flared despite adopting a gluten-free diet. It has been reported that celiac disease-related uveitis responds to a gluten-free diet (Krifa et al.).

Clinical course

The patient experienced overall improvement in intraocular inflammation with topical difluprednate, which is currently being tapered. On her most recent visit, there was one cell per high-powered field in the anterior chamber and trace old-appearing cells in the vitreous bilaterally. Two months prior, the patient experienced a steroid response causing elevated IOP, which has remained controlled with timolol-dorzolamide. Upon completion of the oral prednisone taper, she was transitioned to methotrexate with folate supplementation. She has no plans for pregnancy. Rheumatology has offered its assistance with medication management. Her tattoos have become less edematous (Figure 3). After eliminating gluten from her diet, her diarrhea has ceased.

- For more information:

- Lianna Valdes, MD, is with New England Eye Center, Tufts University School of Medicine.

- Ke Zeng, MD, of New England Eye Center, Tufts University School of Medicine, can be reached at ke.zeng@tuftsmedicine.org.

- Edited by James T. Kwan, MD, and Heba Mahjoub, MD, of New England Eye Center, Tufts University School of Medicine. They can be reached at james.kwan.ophthalmology@gmail.com and hmahjoub@tuftsmedicalcenter.org.