[ad_1]

Here, Alan Nafiiev, CEO and founder of Receptor.AI, discusses the benefits of using large language models to integrate literature evidence and structural prediction to accelerate binding site identification.

Large language models (LLMs) offer a new way to transform unstructured publications into organised, residue-level data that can directly improve structure-based drug discovery. Instead of relying on slow and error-prone manual curation, LLMs can extract binding-site annotations from the literature, align them with protein structures and refine geometry-based predicted binding pockets into biologically validated pocket models.1-3 Benchmarks across diverse proteins show high accuracy and specificity with perfect recall, demonstrating that text-derived evidence can reliably guide pocket prioritisation. In this role, LLMs complement rather than replace geometric and physics-based methods.

The literature bottleneck

In structure-based drug discovery, many challenges arise from the gap between computational predictions and experimental evidence reported in the literature. For example, docking frequently produces several plausible ligand poses, but only a subset corresponds to true binding modes.2 Residue contacts described in publications can serve as filters, helping to identify which poses are biologically relevant.

Molecular dynamics simulations reveal another difficulty: transient or cryptic pockets often appear, but their functional importance is uncertain.3,4 Reports of modulators or functional assays – if systematically mined – provide a way to distinguish meaningful transient sites from simulation artifacts.

[LLMs] can highlight reports of resistance-associated variants in the literature, drawing researchers’ attention to clinically relevant modifications that should be considered in docking or design studies”

Resistance mutations illustrate a further case. In kinases and other clinical targets, single substitutions can reshape binding pockets and cause therapy failure. These effects are extensively documented in oncology publications, yet they remain underused in modelling workflows. While LLMs cannot directly remodel binding sites, they can highlight reports of resistance-associated variants in the literature, drawing researchers’ attention to clinically relevant modifications that should be considered in docking or design studies.4-6

Even the creation of benchmark datasets, essential for evaluating docking or scoring algorithms, could be accelerated by automating residue-level annotations extracted from the literature. This would replace slow, inconsistent manual curation with scalable, literature-grounded datasets.

LLM-based binding pocket extraction

A persistent challenge in structure-based discovery is deciding which of the many cavities predicted by geometry-based algorithms correspond to real binding sites.4 Tools such as Fpocket,7 which identify concave regions on protein surfaces, often produce more candidates than are biologically relevant. Traditionally, researchers validate these predictions by consulting the literature and collecting residue-level binding information scattered across papers. This manual approach is both slow and inconsistent.

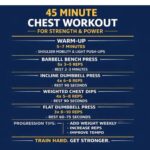

To address this problem, Receptor.AI developed a hybrid workflow8 that integrates geometric prediction with LLM-driven literature mining (Figure 1). The process is as follows: Fpocket first identifies all possible cavities; an LLM then scans publications to extract residues experimentally confirmed to participate in ligand binding. These residues are mapped back onto the protein structure, aligned with Fpocket predictions, and used to merge or filter the geometric pockets. Finally, retained cavities are refined into three-dimensional (3D) volumes by trimming away regions unsupported by residue evidence.

This LLM-guided workflow transforms literature from a passive reference into a structured data source, ensuring that pocket definitions are both geometrically plausible and experimentally validated. It demonstrates how text mining can be integrated directly into structural pipelines, creating a faster and more reliable foundation for downstream tasks such as docking, druggability assessment and ligand design.

Figure 1: Overview of the hybrid workflow. Fpocket predicts candidate pockets; the LLM filters, extracts and validates biologically relevant sites; geometric representations are refined into volumetric grids for downstream use. Credit: Receptor.AI

From text to geometry

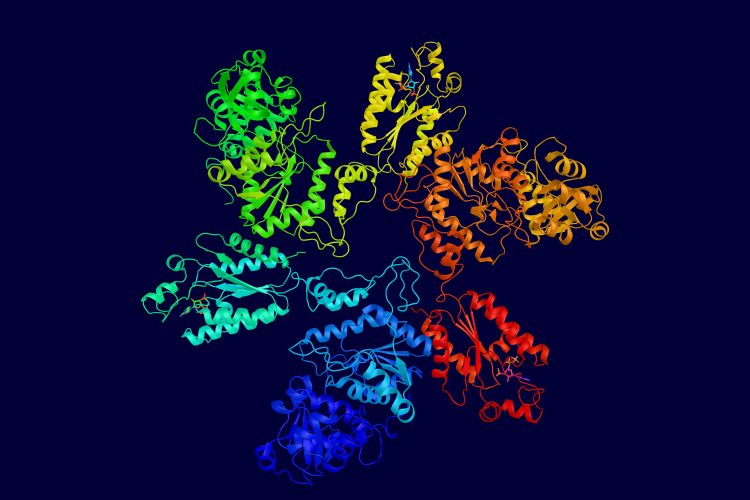

A defining step in the workflow is converting residue lists extracted from papers into spatial pocket models. Residues identified by the LLM are mapped onto the 3D structure and compared against Fpocket predictions. If a literature-derived site overlaps with one or more Fpocket cavities – by residue identity or spatial proximity – these cavities are merged into a single binding region. This is especially important for large active sites that geometry-only methods tend to fragment. For example, kinase ATP-binding clefts are often split into multiple sub pockets by Fpocket; the LLM-guided pipeline recombines them into one continuous catalytic site, consistent with experimental evidence (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Example of pocket merging in a kinase. Panel (a) shows Fpocket’s output for the pseudokinase MLKL (PDB 7MON), where the ATP-binding site is artificially divided into two sub-pockets. Panel (b) shows the unified pocket after LLM-guided merging and refinement, matching the experimentally validated binding site. Credit: Receptor.AI

After merging, pocket geometries are refined further. Fpocket cavities are converted into 3D grids based on alpha spheres, then trimmed using convex hulls defined by the literature-supported residues. This removes stray lobes and solvent-exposed extensions, yielding volumetric models that more accurately reflect true binding environments.

The same principle extends to more complex systems. The GABAA receptor contains two symmetric anaesthetic-binding pockets at distinct subunit interfaces. Fpocket detects cavities at both but cannot establish their functional equivalence. Literature-guided analysis reveals that the anaesthetic etomidate binds in both the A–B and C–D interfaces, ensuring that both are labelled and retained as biologically relevant. More generally, in multimeric proteins or complexes, the contextual awareness provided by LLMs enables correct identification of interface pockets that geometry-only methods may miss or misinterpret.

Conclusion

LLMs now make it possible to convert unstructured publications into structured residue-level annotations and to filter geometrically predicted binding pockets based on these annotations. AI turns what once took days of manual curation into minutes of automated processing.

AI turns what once took days of manual curation into minutes of automated processing”

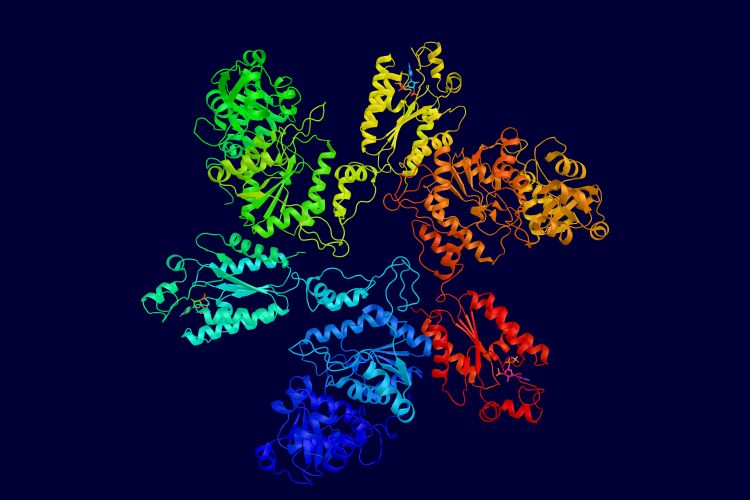

This development comes at a critical moment. The number of protein structures continues to grow rapidly, driven by crystallography, cryo-EM and predictive tools such as AlphaFold. Without scalable annotation, much of this structural information remains underutilised. Literature-aware AI provides a path forward, ensuring that new structures are quickly linked to biologically validated binding sites.

In the broader view, LLMs are emerging as a connective layer between the published record and structural bioinformatics. By enriching computational predictions with experimental evidence, they enable faster and more reliable decision-making and bring the field closer to a future where drug discovery pipelines continuously learn from – and adapt to – the expanding body of biomedical knowledge.

About the author

Alan Nafiiev, PhD, is the CEO and founder of Receptor.AI, a next-generation ‘TechBio’ company advancing a multiplatform ecosystem that features advanced AI-powered platforms for small molecule and peptide design.

Alan Nafiiev, PhD, is the CEO and founder of Receptor.AI, a next-generation ‘TechBio’ company advancing a multiplatform ecosystem that features advanced AI-powered platforms for small molecule and peptide design.

References

- Bhatnagar R, Sardar S, Beheshti M, Podichetty JT. How Can Natural Language Processing Help Model Informed Drug Development?: A Review. JAMIA Open. 2022.

- Gagliardi L, Raffo A, Fugacci U, et al. SHREC 2022: Protein-Ligand Binding Site Recognition. arXiv (Cornell University). 2022.

- Krapp L, Abriata LA, Cortés Rodríguez F, Matteo Dal Peraro. PeSTo: Parameter-Free Geometric Deep Learning for Accurate Prediction Of Protein Binding Interfaces. Nature Comm. 2023;18;14(1).

- Lee J, Zhung W, Seo J, Kim WY. BInD: Bond and Interaction‐Generating Diffusion Model for Multi‐Objective Structure‐Based Drug Design. Advanced Sci. 2025.

- Lu J, Choi K, Eremeev M, et al. Large Language Models and Their Applications in Drug Discovery and Development: A Primer. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2025;18(4).

- Ye G. De Novo Drug Design as GPT Language Modeling: Large Chemistry Models With Supervised and Reinforcement Learning. J. Comp. Mol. Des. 2024;38(1).

- Le Guilloux V, Schmidtke P, Tuffery P. Fpocket: An Open Source Platform for Ligand Pocket Detection. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(1):168.

- LLM-Driven Binding Pocket Prioritization. [Internet] Receptor.AI. Available from: https://www.receptor.ai/news-and-blogs/llm-driven-binding-pocket-prioritization

[ad_2]

Source link