October 09, 2025

3 min read

Key takeaways:

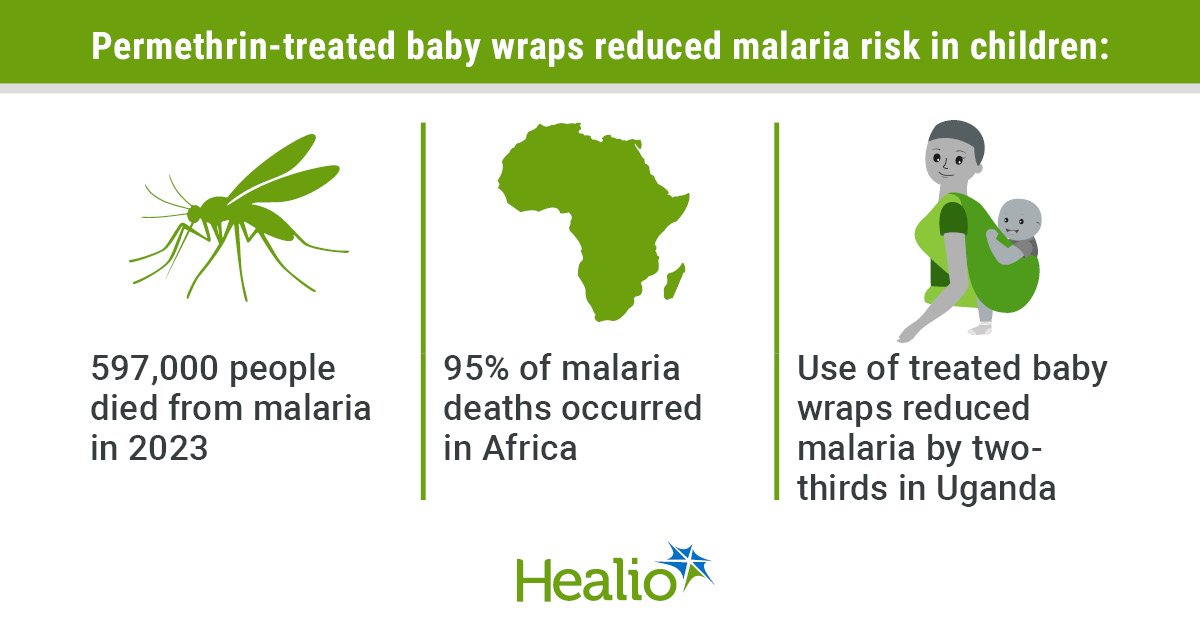

- Researchers integrated malaria prevention into daily life by adapting cultural practices of baby wrap use.

- Use of treated baby wraps was associated with a two-thirds reduction in malaria cases.

Permethrin-treated baby wraps, used alongside bed nets, significantly reduced malaria cases among children aged 6 to 18 months in Uganda, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

WHO’s 2024 World Malaria Report estimated there were 597,000 malaria deaths in 2023, with approximately 95% of them occurring in the WHO Africa Region, where children aged younger than 5 years accounted for around three out of every four deaths.

Data derived from Boyce RM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2025;doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2501628.

In the new study, researchers incorporated the lesu, a wrap used to carry children from infancy to 2 years of age in Western Uganda, into malaria prevention efforts for this vulnerable population.

“Trying to get everyone in malaria-endemic areas to wear treated clothing is probably too ambitious, but targeting young kids, who are the most vulnerable, seemed viable,” Ross M. Boyce, MD, MSc, associate professor of medicine and assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine, told Healio. “From there, it’s a pretty easy leap to the wraps which are widely, if not almost universally, used.”

The double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial included 400 mother-child pairs, with the mothers all aged 18 years or older and the children aged 6 months to 18 months.

The intervention group, composed of 200 mother-child pairs, received bed nets and baby wraps treated in a 0.5% permethrin solution. The baby wraps were re-treated every 4 weeks. The control group, made up of the other 200 mother-child pairs, received bed nets and baby wraps that underwent a “sham” treatment by being soaked in water.

Boyce and colleagues followed the participants for 24 weeks between June 2022 and April 2024, checking in with them every 2 weeks at trial clinics where children with malaria symptoms were given a diagnostic test and treatment. No participants were lost to follow-up and 99.9% of planned clinical visits were attended.

Participants reported using bed nets to provide protection at night — the lesu was used during the day — more than 99% of nights.

Overall, the researchers reported a clinical malaria incidence of 2.14 cases per 100 person-weeks (95% CI, 1.73-2.62) in the control group compared with was 0.73 cases per 100 person weeks (95% CI, 0.51-1.02) in the intervention group, a reduction of nearly two-thirds.

“Quite frankly, the magnitude of the effect — namely a nearly two-thirds reduction in malaria — was substantially larger than we anticipated, especially with all participants receiving new bed nets,” Boyce said. “I did not think that transmission at times when children were not under a net would be so important.”

The researchers also monitored the groups for adverse effects from the treated wraps. Rash occurred more frequently in the intervention group than in the control group (8.5% vs. 6%), but none of the rashes were severe enough to lead to trial discontinuation.

The researchers noted some study limitations, including its limited generalizability beyond cultures that use baby wraps similarly and an undisguisable odor present in permethrin-treated wraps. Still, participant surveys showed high confidence in the benefits of treated wraps across both groups, mitigating concerns about the blinding being compromised due to the odor.

Boyce believes the most pressing research moving forward is evaluating the best methods to treat and re-treat baby wraps with permethrin, an insecticide chosen by the researchers “because of its demonstrated efficacy, commercial availability, and established safety record,” they wrote.

“We retreated the wraps every month to make sure that washout was not an issue,” Boyce said. “Now we have to tackle the wash-out issue because frequent retreatment is likely to be very difficult to achieve at scale. The technology to do that is well established. There’s a number of commercial products, clothing for example, that have Environmental Protection Agency approvals for up to 50 washes per year.”

Factory permethrin treatment may last longer in Uganda, because drying machines are not commonly used there, according to Boyce.

Boyce believes implementing permethrin-treated wraps may complement existing malaria prevention strategies, such as vaccines, because the first of four malaria vaccine doses is typically given to 5- to 6-month-old infants, and the first dose does not confer immediate protection.

“One could envision using the wraps from infancy to approximately 2 years of age — culturally, this is how they are used now — which could help bridge kids such that they emerge out of the wraps with full vaccine-induced immunity,” Boyce said.

Even though U.S. foreign aid cuts have impacted global malaria elimination efforts, Boyce thinks local production of treated wraps at a low cost is possible in countries with the manufacturing capacity. He is more concerned that the cuts are impacting access to basic equipment such as diagnostic tests, medications and bed nets.

“Progress against malaria had been backsliding in many of the high-burden countries in sub-Saharan Africa even before these cuts,” Boyce said. “With some of the hits malaria-control programs are taking, we could see the bottom fall out once existing supplies are used up.”

For more information:

Ross M. Boyce, MD, MSc, can be reached at roboyce@med.unc.edu.