By Mike Borella –

One might be forgiven for assuming, based on a cursory reading of the Constitution or perhaps a fleeting bout of logic, that the U.S. patent system exists to promote the progress of science and useful arts. Historically, this meant incentivizing inventors to create tools that reduced human drudgery, increased accuracy, and generally made life less miserable for the species.

However, under the current jurisprudence of the Federal Circuit, patent law lives in a fascinating dystopia – the more an invention is described in terms of its utility to human beings (e.g., saving time, organizing data, reducing errors), the more likely it is to be summarily executed under 35 U.S.C. § 101. Welcome to the usefulness paradox, where the very benefits of an invention are used as evidence against its eligibility.

To understand the absurdity of the current moment, we first look at what the Patent Office used to consider worthy of protection. Let us review a few inventions that, under today’s Section 101 analysis, would likely be categorized as abstract “fundamental practices” or “methods of organizing human activity.”

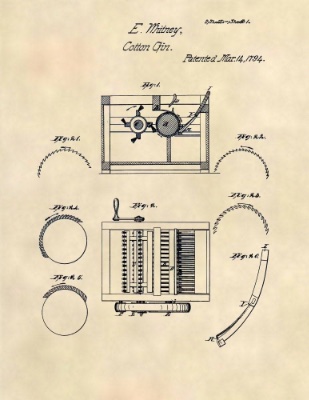

- Eli Whitney’s Cotton Gin (1794). The invention was a machine that separates cotton fibers from their seeds. Today, a § 101 contention would write itself: “The act of separating desirable objects from undesirable objects is an abstract practice performed by humans since the dawn of agriculture. The rollers and brushes are merely generic mechanical components performing their expected functions.”

- Alexander Graham Bell’s Telephone (1876). The claim covers “the method of, and apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically.” Under the modern interpretation of § 101, this invention could be viewed as the abstract concept of human communication over a distance with the electric wire just a generic conduit.

- Thomas Edison’s Light Bulb (1880). Another loser in view of the current law that is drawn to the abstract idea of “generating incandescence by heating a resistive wire through conduction of electricity.” Further, the additional elements of metallic wires, glass, and a closed chamber, were in routine use at the time of the invention.

These inventions defined the modern world. They were patentable because they provided a solution to a physical problem formerly performed by humans (e.g., separating seeds from cotton, sending messages from place to place, and providing illumination in dark environments, respectively). They involved some degree of making a human task more efficient and useful through machinery. In each case, the machinery performed the task differently than humans had previously.

This notion of new and useful machines being patentable was prevalent in the Industrial Age, but has not survived unscathed in today’s Information Age. The Federal Circuit appears to view computer-implemented methods as being fundamentally different from those carried out by other types of non-computer automation. Indeed, a thread running through the last 11 years of § 101 jurisprudence is that if a human could perform a task (no matter how slowly or poorly), a computer doing it differently and better is likely ineligible. The fact that the computer can, in practice, achieve a useful result that a human could not appears to be irrelevant. Let’s consider some examples.

In Yu v. Apple Inc., the invention was a digital camera system that used two separate image sensors and lenses to create a single, higher-quality image. This is a classic hardware-software hybrid invention designed to overcome the physical limitations of single camera lenses. The Federal Circuit found it ineligible. Why? Because photographers have been taking pictures for a long time. The Court reasoned, “[t]he claim is directed to the abstract idea of taking two pictures . . . and using one picture to enhance the other in some way . . . the idea and practice of using multiple pictures to enhance each other has been known by photographers for over a century.” By this logic, the fact that a human could manually overlay two film negatives in a darkroom renders a real-time, digital signal processing invention abstract. The court reduced a complex technical configuration of sensors and lenses to the fundamental human activity of taking photos.

In IBM Corp. v. Zillow Group, Inc., the patent involved a method for displaying search results in a way that contextually adjusted based on user input – an improvement in how humans interact with database systems. The Federal Circuit affirmed invalidity, stating, “[t]he claims . . . do nothing more than improve a user’s experience while using a computer application [and fail to] do anything more than identify, analyze, and present certain data to a user, which is not an improvement specific to computing.”[1] The Court is effectively saying that making a computer easier for a human to use is not a technical improvement to the computer. In doing so it separates user experience from technology, as if the entire purpose of a computer isn’t to be used by and provide utility to humans.

The inanity escalates with Recentive Analytics Inc. v. Fox Corp. The invention was a machine learning method for optimizing event schedules (like TV broadcasts) by analyzing vast arrays of constraints. This replaces a logistical nightmare with an optimized, AI-driven schedule. The Federal Circuit found it ineligible because optimizing a schedule is a human concept, and using AI to do it (differently) is just generic. Notably, “the use of machine learning to achieve this result is merely the application of a generic computer tool.” This holding suggests that if AI is used to solve a problem that a human understands (like scheduling), the AI itself is just a generic tool for an abstract idea. The Court punished the invention for being useful in a domain that humans care about.

The tragic irony of this jurisprudence is that it incentivizes patent practitioners to draft applications that obfuscate the actual benefit of the invention. If you write a patent application today that states that the invention helps the user take better photos, you have handed the examiner a loaded gun. They can cite Yu and say you are merely automating the abstract idea of picture enhancement. If you write, “this invention makes the interface more intuitive,” they can cite IBM and contend that the invention is focused on user experience rather than technical functionality. We have reached a point where the usefulness requirement of § 101 is being used to negate eligibility.

The downside to the public good is palpable. We are effectively telling innovators in consumer electronics, user interface design, and applied AI that their work is not technology, but merely convenience. This outcome ignores the fact that in an information economy, the ability to process, visualize, and interact with data is the technology. If we continue to interpret abstract ideas as anything that a human could theoretically do regardless of time, error rate, or physical capability we are not protecting the public from monopolization of fundamental truths. We are preventing the public from accessing the specific applications that make those truths usable.

[1] Even a casual glance at the detailed claims of the patent in question calls this statement into question.