Emergency physicians, along with physician assistants and nurse practitioners, are increasingly using generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools for fast access to medical information. This spans from general-purpose large language models (LLMs) like Google’s Gemini, Anthropic’s Claude, and OpenAI’s ChatGPT, to domain-specific platforms like OpenEvidence, which is grounded in evidence-based, peer-reviewed literature.1,2

General purpose AI tools tend to excel at providing background information, patient-friendly discharge instructions, and supporting research brainstorming. In contrast, clinician-specific tools like OpenEvidence are better suited for patient-specific queries that require accuracy, citations, and guideline-concordance, all of which are grounded in attributable sources.

Although the quality and nature of outputs can vary greatly between different LLMs that power AI tools, the value and safety of AI is not intrinsic to the models themselves. Rather, it is about the quality and nature of the interaction between the AI and the human. This interaction is the “prompt:” that blank space where a human poses a question to the AI.

Poorly constructed prompts can lead to irrelevant, nonsensical, and nonactionable answers. They can also increase the likelihood of factually incorrect information, termed “hallucinations.”3 Hallucinations are more common when incomplete information is given to the AI, leaving the AI to fill in gaps. AI tools can create fake scientific facts claimed to be backed by evidence or even generate references that do not exist. AI models can also inherit or even amplify biases present in the data that feeds them, perpetuating health care disparities.4

How to “prompt” is not yet a skill emergency physicians and APCs are typically taught, but it is a skill that is becoming increasingly important with the growth of general and medical-specific AI.

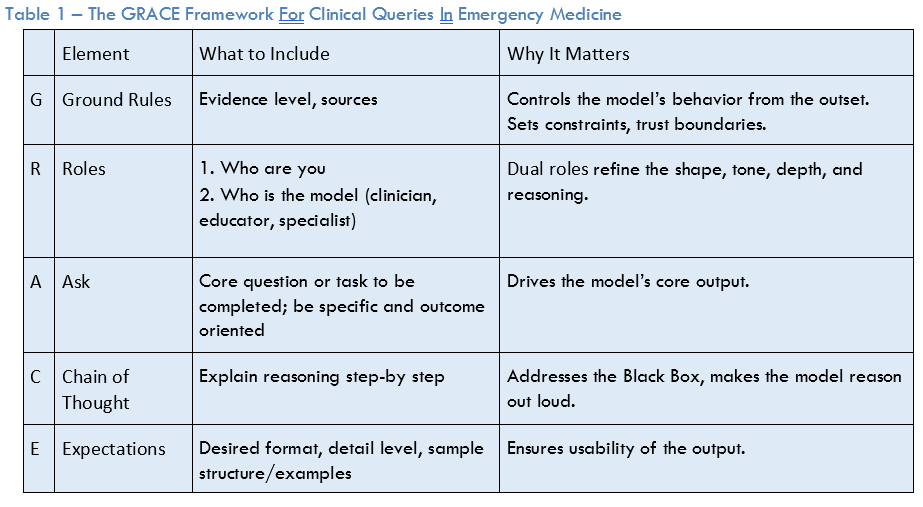

To optimize AI prompting, a systematic approach is needed to ensure reliability, trustworthiness, and consistency in that outputs are clinically relevant, accurate, and actionable.2 One such novel framework for prompt engineering for medical queries is called GRACE (Ground Rules, Roles, Ask, Chain of Thought, Expectations), which is designed for emergency physicians and APCs in acute care.

The GRACE framework (see Table 1) involves first setting ground rules—the “G” in GRACE. These set boundaries, constraints, and evidence standards for the AI’s response. This is important as AI models tend to anchor to terms at the beginning of the prompt and clear ground rules can reduce the likelihood of hallucinations. An example of ground rules may be “source-published, verifiable literature. Provide citations. Do not invent sources.” This is particularly important in queries to chatbots, like ChatGPT. Although it may be obvious that this is desired, explicitly telling the AI sets guardrails on the output and can lower the likelihood of hallucinations or other erroneous output.

Next, is the “R.” Assigning role(s) is a highly effective method for controlling style, tone, and depth of output. The concept of dual roles (user-AI) can enhance this further. For example, “I am an emergency medicine resident, you [i.e., the AI] are an experienced emergency medicine attending.”

The “A” is for the ask. This is the core question or task that the prompt is asking the AI to accomplish. For the ask, the key is to be explicit and focused to define exactly what you want the AI to do. For example, stating that you are looking for treatment recommendations, guidelines, or a differential diagnosis. Or it may involve entering a clinical case scenario into the AI with a specific question.

The “C” is for chain of thought. Asking the AI to “explain your reasoning step-by-step” is a simple, yet powerful method to expose the AI’s reasoning process to the clinician and can improve output performance. Answering not just the “what,” but the “why” gets around the “black box” problem where the user may not understand why the AI has concluded what it has. To see the effect of asking for chain of thought, ask ChatGPT 4 which antibiotic you should use to treat pneumonia in the emergency department. Now, start a new conversation and ask the same question with “show your reasoning step by step” included.

The “E” is for expectations, which help ensure the usability of the response for the question at hand. For a busy emergency physician or other members of the team, a concise bulleted list of differential diagnoses is far more valuable than a dense multi-paragraph response. Example phrases to use include, “provide the bottom line up front” or “be brief and concise.”

Ultimately, the value of AI for clinical queries is contingent upon the quality and nature of the interaction between the clinician and the AI system: effective prompting. This is a skill that 21st-century emergency physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, are likely to require. A structured framework like GRACE can provide a more predictable, reliable, and usable experience while being uniquely grounded in the cognitive workflows of acute care clinicians.

Dr. Fitzgerald is the Interim Director of Generative AI and Workflow Engineering at US Acute Care Solutions and a hospitalist at Martin Luther King, Jr. Hospital in Los Angeles, Calif.

Dr. Fitzgerald is the Interim Director of Generative AI and Workflow Engineering at US Acute Care Solutions and a hospitalist at Martin Luther King, Jr. Hospital in Los Angeles, Calif.

Dr. Caloia is the Chair of National Clinical Governance Board at US Acute Care Solutions and core faculty at the Henry Ford Genesys EM residency program in Grand Blanc, Mich.

Dr. Caloia is the Chair of National Clinical Governance Board at US Acute Care Solutions and core faculty at the Henry Ford Genesys EM residency program in Grand Blanc, Mich.

Dr. Pines is the Chief of Clinical Innovation at US Acute Care Solutions and a Clinical Professor of Emergency Medicine at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

- Kachman MM, Brennan I, Oskvarek JJ, et al. How artificial intelligence could transform emergency care. Am J Emerg Med. 2024; 81:40-46.

- Patil R, Heston TF, Bhuse V. Prompt engineering in healthcare. Electronics. 2024;13(15):2961.

- Grimes K. How to Use Generative AI and Prompt Engineering for Clinicians [webinar]. BMJ Future Health; 2024.

- Piliuk K, Tomforde S. Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine: a systematic literature review. Int J Med Inform. 2023; 180:105274.