October 08, 2025

5 min read

Key takeaways:

- Adults with only one tattoo session had slightly elevated melanoma risk compared with tattoo-free individuals.

- Melanoma occurred less frequently among adults with multiple tattoos.

A population-based study designed to examine the impact tattoos may have on a person’s risk for melanoma revealed a surprising disparate pattern.

Adults who had only one tattoo session exhibited a slightly elevated risk for melanoma — particularly in situ disease — compared with tattoo-free individuals.

Data derived from McCarty RD, et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2025;doi:10.1093/jnci/djaf235.

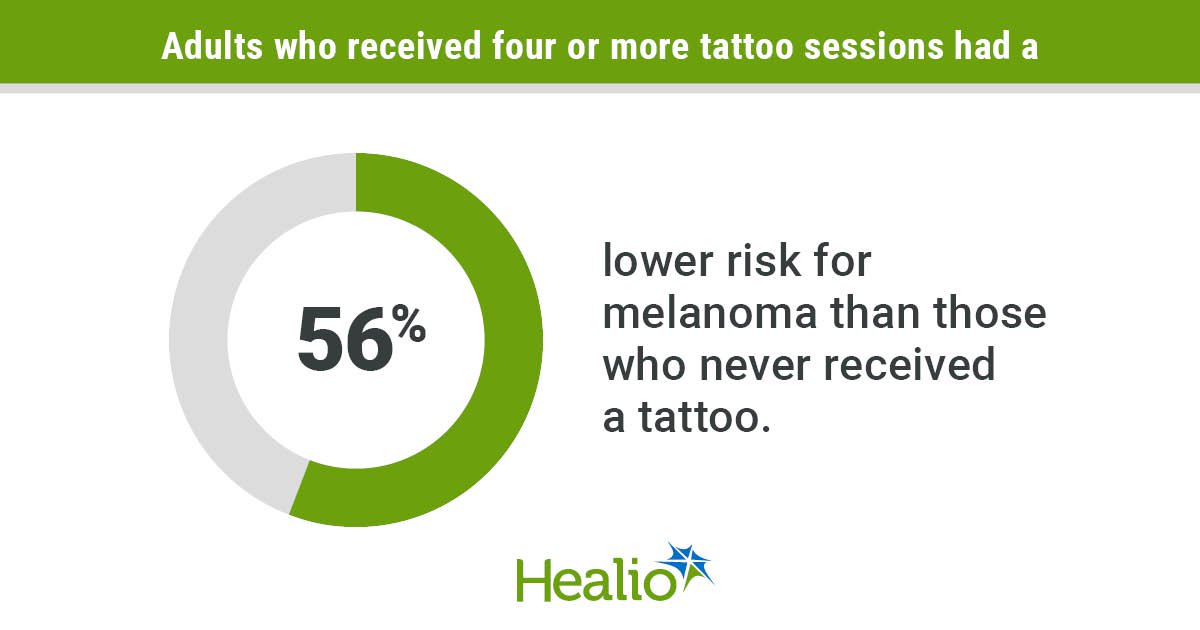

However, people who had multiple tattoos exhibited significantly lower risk for melanoma — both in situ and invasive disease — than those who had never been tattooed.

Jennifer A. Doherty

“We are not sure why we are seeing this small increase in risk with one tattoo session but a very clear decreasing risk with additional tattoo sessions,” Jennifer A. Doherty, MS, PhD, co-leader of the cancer control and population sciences program at Huntsman Cancer Institute and professor of population health sciences at The University of Utah, told Healio. “More research absolutely needs to be done.”

Not just art

Nearly one-third of U.S. adults have a tattoo and about one in five have more than one, according to a Pew Research Center survey released in 2023.

Nearly half of adults aged 30 to 49 years have at least one tattoo compared with 13% of those aged 65 years or older, survey results showed.

However, few studies have examined potential health risks associated with this trend.

Tattoo ink — both the pigments themselves and the carrier solution — can contain carcinogens that are retained in the lymph nodes, and new carcinogens can form as the ink breaks down.

Tattoos also can trigger inflammatory responses. It is well known that tattoos can “light up immunologically” even years after placement, Doherty said.

Prior research suggests tattoo exposure may elevate risk for certain types of lymphoma. However, associations between tattoos and melanoma risk have not been studied on a population level.

Doherty and colleagues hypothesized that individuals with more tattoos would have higher melanoma risk — partly based on the suspected mechanisms through carcinogens in inks and inflammation and partly based on growing evidence that suggests individuals with tattoos tend to take more risks, Doherty said. For example, statewide data in Utah showed people with tattoos were more likely to report that they smoke cigarettes or binge drink, and that they have poorer health compared with non-tattooed individuals, she said. They also were less likely to receive flu or COVID-19 vaccinations.

“This made us wonder about sun hygiene. It is possible that some people with tattoos have increased sun exposure because of risk-taking tendencies or may desire their tattoos to be visible,” Doherty said.

At the same time, tattoo artists recommend using sunscreen to protect tattoos from fading.

Prior data from three studies on sun protective behaviors among tattooed individuals is mixed, with some reporting tattooing being associated with history of sunburns, tanning bed use and never use of sunscreen, and others reporting both heavier sun exposure and greater use of sun protection.

Surprising patterns

The researchers used the Utah Cancer Registry to identify all adults ages 19 to 79 years diagnosed with in situ or invasive melanoma between Jan. 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, in Utah.

Investigators invited these adults to complete a survey based on the Utah Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey, with extra questions about tattooing. They added the same three questions specific to tattoos to the Utah BRFSS, and used BRFSS respondents who were similar to the tattooed cases with regard to age, sex and race and ethnicity to establish a cohort of frequency-matched controls.

The analysis included 1,167 people with melanoma (invasive, n = 601; in situ, n = 566) who responded to telephone surveys and 5,835 controls.

Researchers determined 12% of those with melanoma and 15% of controls had at least one tattoo.

Results showed no association between ever being tattooed and melanoma risk (overall, OR = 0.92; 95% CI, 0.74-1.13; invasive melanoma, OR = 0.81; 95% CI, 0.6-1.09).

However, patterns differed considerably by the amount of tattoo exposure.

Those who reported only one tattoo session exhibited increased overall risk for melanoma compared with those who never received a tattoo (OR = 1.53; 95% CI, 1.16-2). The risk for invasive melanoma did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.25; 95% CI, 0.85-1.83).

Results showed significantly lower melanoma risk among individuals who received four or more tattoo sessions (overall, OR = 0.44; 95% CI, 0.27-0.67; invasive, OR = 0.43; 95% CI, 0.24-0.8). Researchers observed the same pattern among adults who reported having three or more large tattoos, defined as bigger than their palm (overall, OR = 0.26; 95% CI, 0.1-0.54; invasive, OR = 0.23; 95% CI, 0.07-0.75).

Receipt of a first tattoo prior to age 20 was associated with reduced risk for invasive melanoma compared with no tattoo history (OR = 0.48; 95% CI. 0.29-0.82).

‘Cautious’ interpretation

Study limitations — particularly a lack of data about sun exposure behaviors among controls — require “cautious” interpretation of the findings, Doherty said.

Limits on the number of questions that could be added to the BRFSS prevented researchers from collecting data in the control group about risk factors such as indoor tanning, sun-protective behaviors and sunburn history, hair and eye color, or family history of melanoma. Investigators also could not ask controls questions about tattoo sun exposure.

In contrast, the telephone surveys administered to melanoma survivors allowed researchers to glean information about their behaviors and risk factors.

When Doherty and colleagues surveyed adults with melanoma, they observed a strong association between tattoo history and increased tanning bed use, an established risk factor for melanoma.

“We were worried that would be a confounder that would explain increased melanoma risk among tattooed individuals had we observed it,” Doherty said. “However, if we were to accept that assumption that tattooing is associated with increased tanning bed use among people with and without melanoma, then — had we controlled for that in our analysis — we would have seen an even further decreased melanoma risk with tattooing.”

‘Tip of the iceberg’

It is not implausible that there is “a real association” between tattooing and lower melanoma risk, Doherty said.

“One idea is that tattoos stimulate an immune response, sparking immune cells to identify and clear nascent tumor cells,” Doherty said.

Another theory is that ink on the skin absorbs UV radiation, resulting in decreased backscattered radiation exposure.

However, no mechanistic studies have been conducted to investigate those possibilities.

The lowered risk also could be tied to increased sun protection behaviors among people with multiple tattoos, Doherty said.

Data on tattooing along with detailed data on melanoma risk factors — including sun exposure and sunscreen use — are “urgently needed” to understand associations between tattoo exposures and melanoma risk after accounting for sun safety behaviors, Doherty said.

“The prevalence of tattooing is increasing dramatically and the decision about whether to get one is very personal,” Doherty said. “When we started this most recent study, we wanted to provide information that could help people make a benefit-harm calculus. The results we have so far don’t provide enough information — much more research is needed — but at least it’s the tip of the iceberg.”

For more information:

Jennifer A. Doherty, MS, PhD, can be reached at jen.doherty@utah.edu.