Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. For more information see out Terms and Conditions.

In today’s blog post we’re going to answer 3 questions:

- What are the mechanical factors associated with Plantar Heel Pain (PHP)?

- Why are they important?

- How can we address them in rehab?

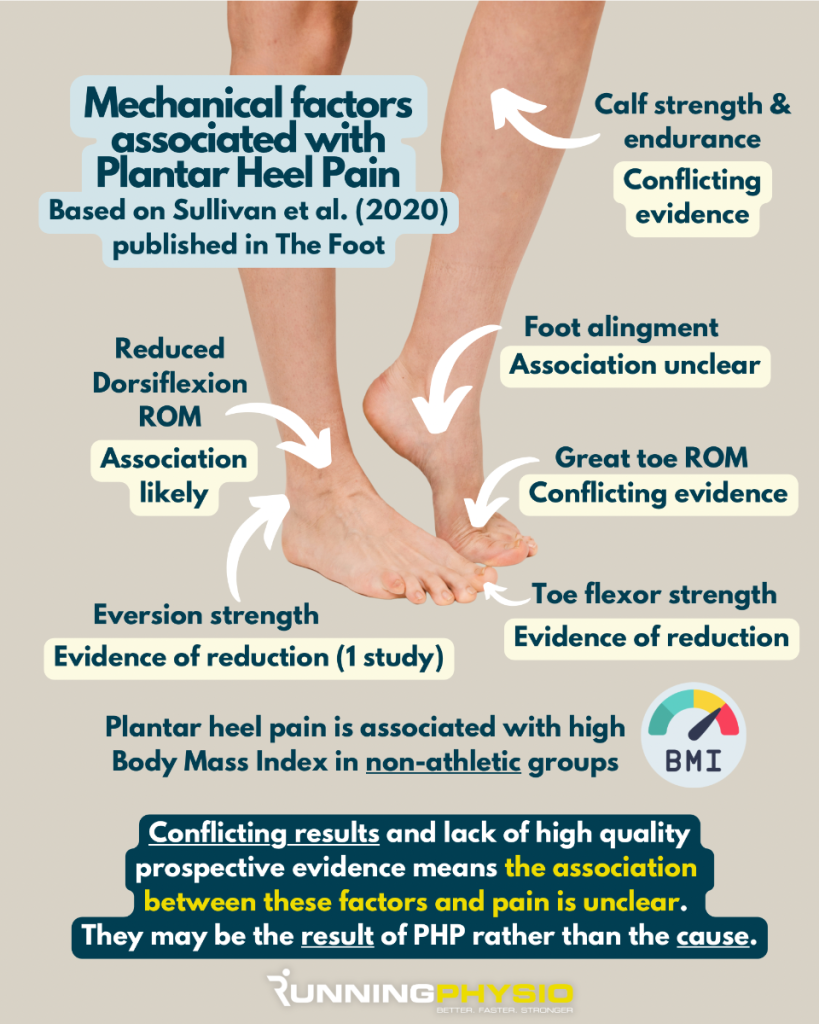

First up, let’s look at the mechanical factors in PHP. There’s a nice paper on this from Sullivan et al. (2020) which I’ve summarised for you in the graphic below:

As you can see from the graphic the evidence here is mixed, I suspect this is largely down to individual variation and the populations studied.

These are still areas that are important to assess as each can influence the load on the plantar fascia and therefore be implicating in PHP. For example reduced ankle dorsiflexion due to joint restriction or calf tightness:

“Lack of ankle dorsiflexion during the stance phase of the gait cycle could potentially lead to a compensatory increase in midfoot dorsiflexion motion (41), essentially lowering the arch further and increasing tensile load on the plantar fascia… it is feasible that increased tensile load on the gastrocnemius-soleus complex due to inflexibility could transmit directly to the plantar fascia.” Sullivan et al. (2020)

Reference 41: M.A. Karas, D.J. Hoy Compensatory midfoot dorsiflexion in the individual with heel cord tightness: implications for orthotic device designs J Prosthet Orthot, 14 (2002), pp. 82-93

It seems that association is likely with reduced ankle dorsiflexion and decreased toe flexor strength, and PHP has been connected with high BMI in non-athletic groups.

Sullivan et al. (2020) note that the association between heel pain and foot alignment is unclear, plus there is limited evidence to suggest heel pain is associated with running mileage or weight-bearing at work.

Important to note that ‘limited evidence’ doesn’t mean there isn’t an association, just that there currently isn’t much evidence that conclusively shows what that relationship is.

I think we’ve covered the first 2 questions, so it’s on to question 3…

How can we address these factors in rehab?

As with most conditions, good treatment starts with a good assessment! In patients with PHP, I would typically include the following:

- Strength testing – calf, ankle inversion and eversion, plus great toe flexion

- Range of movement – especially ankle dorsiflexion and great toe extension

- Static and dynamic foot posture – particularly during goal activities and aggravating factors

- Activity levels and pain – explore daily activities and sport

- Footwear options and symptom response – aim to identify the best option for the patient to help reduce symptoms

- General health and previous medical history – discuss relevant comorbidities (which may include weight management)

I’m sure there are other options that we could add to this list, including psychosocial factors, but what I’ve included above should help you identify which mechanical factors may be relevant to the individual you’re seeing.

An individualised approach is key as PHP can affect a broad range of different people and populations.

I’ve seen it in sedentary people, athletes and ultra-endurance runners!

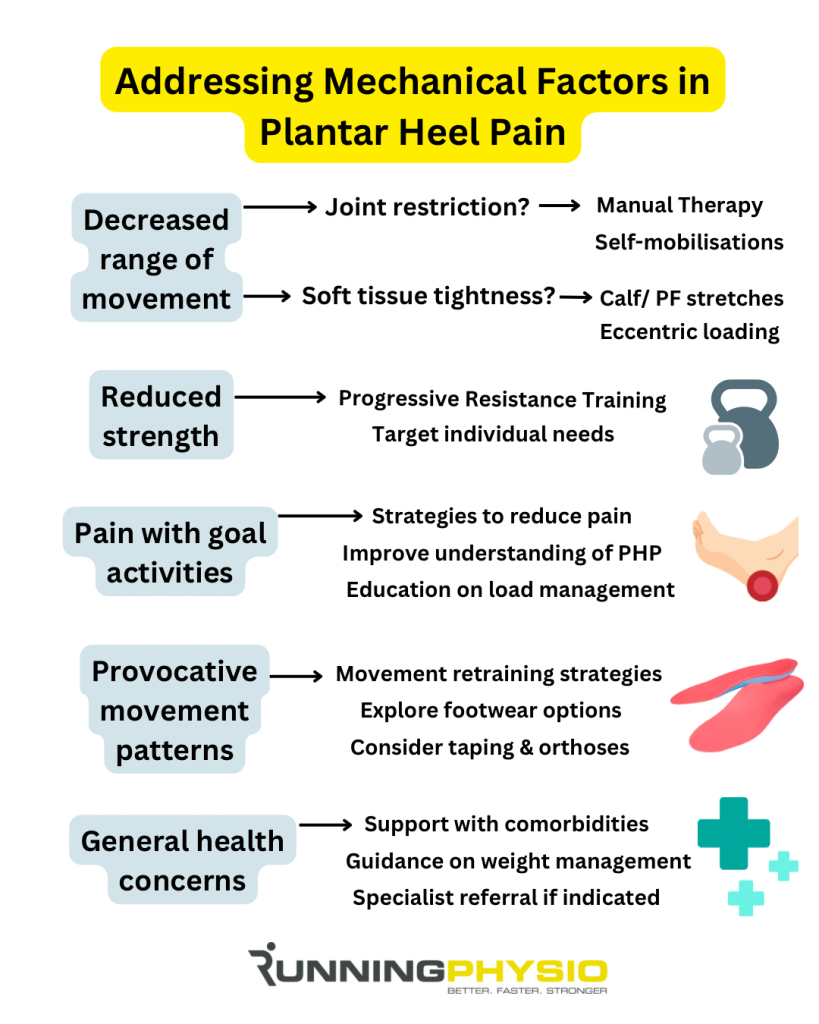

Here are some suggestions on how we may address key factors that we find in our assessment:

Many of these are in line with the recent guidelines we discussed in last week’s blog post (insert link here). Other treatment options, such as shockwav,e can be considered, especially if the approaches above haven’t been effective.

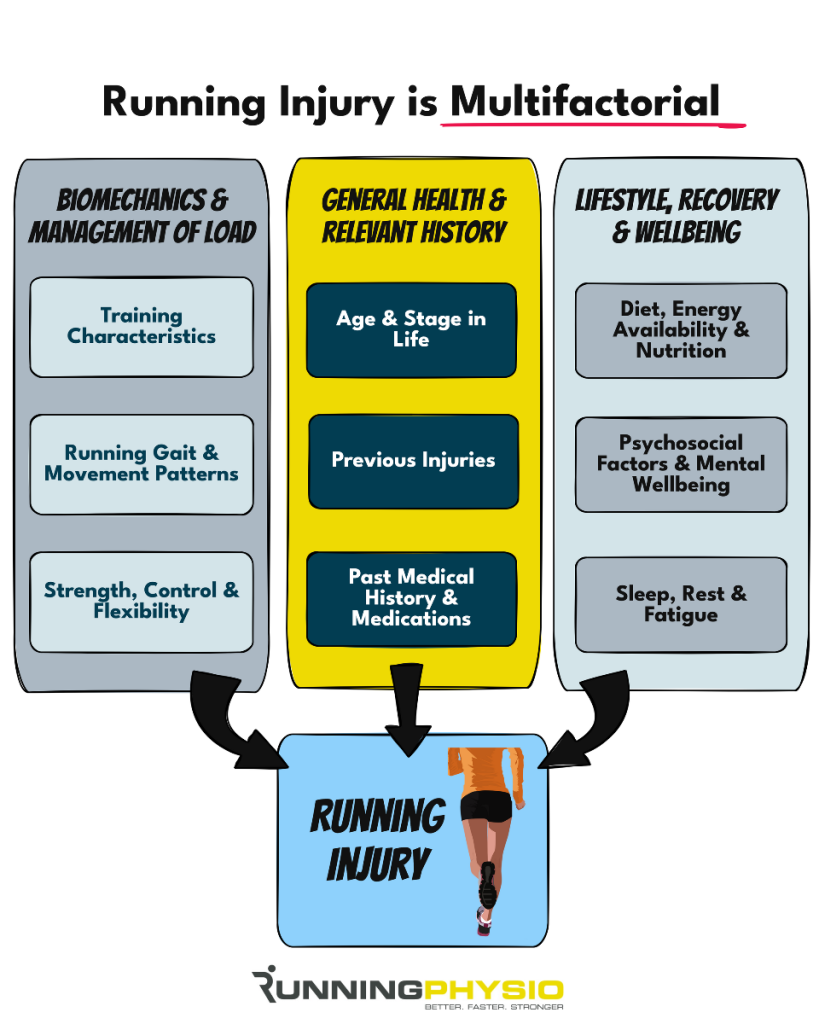

A final point to add is that we’ve focused on mechanical factors here. That term, ‘mechanical’, always makes me feel like we’re discussing machines! We’re not, we always treat a person rather than a pathology, with biomechanics and loading being one part of a much bigger picture!