Author: Sonika Raj, MD (Assistant Professor of EM, University of Texas Southwestern) // Reviewed by: Jessica Pelletier, DO, MHPE (Assistant Professor of EM/Assistant Residency Director, University of Missouri-Columbia); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

“This patient doesn’t need to be admitted.”

“I’m not leaving without a prescription for an antibiotic.”

“If you discharge me today, we’re going to have a problem.”

Consider your last few shifts in the Emergency Department (ED). When was the last time you encountered conflict? Have you ever heard any of these statements from a patient or colleague? When you imagine the conflicts embedded in these scenarios, do you feel tense? How might you handle the angry, frustrated, or combative party on the other side of the discussion?

The team-based, high-stakes, complex nature of healthcare often creates interactions burdened by conflict.1 The time and energy required to manage this well can detract from patient care.2 Therefore, it behooves emergency physicians to learn how to manage conflict both effectively and efficiently. This requires one to confront and solve problems using professional, open communication that consistently prioritizes safe and effective patient care.1 Mastering this challenging skill is both crucial to success in medicine and a valuable catalyst for personal and professional growth.

What is conflict, and in what settings do we encounter conflict in the ED?

Conflict arises when two parties differ in their expectations, agendas, interests, personal needs, backgrounds, and/or communication styles.3 It can also be thought of as a breakdown in trust shaped by history between the parties, emotion inherent to the situation, and connected to any external stressors, structure, the parties’ values, and communication.4,5 Another definition of conflict is the perception of “mutual interference.” This often arises in cases of resource scarcity, goal incompatibility, interpersonal differences, and/or differences in communication styles.6

The idea of conflict typically holds a negative connotation.6 However, conflict may be considered positive (i.e., the interactionist view), natural (i.e., the human relations view), or negative (i.e., the traditional view).6 Whatever the lens, conflict must be managed in such a way that attends to both parties’ needs and goals.6 In healthcare, this is particularly important because ineffective conflict management can result in medical errors, litigation, low job satisfaction, poor team cohesion, low productivity, and strain on the system in general.6

In the ED setting, most conflicts may be classified into one of three categories: task content, interpersonal, and process-related.6 Examples of conflicts related to task content are disagreements about the indications for diagnostic testing and inappropriate prescription requests from patients. Conflicts related to interpersonal differences may involve disputes among physicians, nurses, learners, patients, and family members. Examples of process-related conflicts include discussions surrounding disposition decisions, throughput times, consultant recommendations, and resource allocation.

A 2014 multicenter qualitative study, conducted by Chan et al. and involving 61 emergency medicine, internal medicine, and surgery residents and attendings, provided some insight into conflict in the healthcare environment. The goal of the study was to explore how learners should be taught about ED consults.1 Consults create the opportunity for collaboration – and therefore, for conflict when efforts at collaboration fail.1 Consultants are often unaware of how decisions in emergency medicine must often be made with incomplete information in unpredictable circumstances, and how this can create cognitive and emotional burdens that easily lead to conflict.2 When interviewed, all of the participants in this study were able to recall examples of conflict that arose during recent consults, and were able to identify various factors that both mitigated and produced conflict (Table 1).1

Table 1. Conflict-Causing and Conflict-Mitigating Themes

| Factors | Conflict-mitigating Themes | Conflict-producing Themes |

| Historical factors | Good reputation

Good prior experiences |

Bad or unknown reputation

Doubt in other party’s competence (based on prior experiences) |

| Attitudes and values displayed | Empathy

Engagement Professional behavior |

Disengagement |

| Actions taken | Agreeing with plan of care

Collaboration Meeting expectations Provision of expert care adjusting expectations |

Disagreeing with plan of care

Failing to collaborate Failing to meet expectations Poor communication Self-serving behaviors |

| Trust | Presence | Absence |

| Others | External stressors |

Modified from: Chan, Teresa, et al. “Conflict Prevention, Conflict Mitigation, and Manifestations of Conflict during Emergency Department Consultations.” Academic Emergency Medicine, vol. 21, no. 3, Mar. 2014, pp. 308–313, https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12325.

In a similar vein, a 2024 systematic review conducted by Tjan et al. identified that conflicts were common during both ED consults and admissions.3 This study aimed to “synthesize the individual-, team-, and systemic-level factors that contribute to conflict between clinicians within the ED.”3 Individual-level factors included distrust in the ED workup, personality incompatibilities, lack of familiarity, inexperience, and lack of self-confidence.3 Team-level factors included in-group/out-group bias, stereotypes about specialties, patient complexity, disagreements over dispositions, communication errors, and differences in practice styles.3 Systems-level factors included workload, time constraints, ambiguities at the time of handover, power dynamics, and overall environmental culture.3

Lastly, it is important to note that the asymmetry inherent to the doctor-patient relationship can be another setup for conflict, especially when this is coupled with differing perspectives on illness severity, sociocultural barriers, and/or language barriers.7 On top of this, physicians often self-sabotage the physician-patient relationship by adopting an authoritarian stance.7 This rigid approach to patient care, even with the best of intentions behind it, can ruin communication and the chance for collaboration by implicitly dismissing patient concerns and worries.7

What evidence-based approaches to conflict management currently exist?

Currently, there exist four main evidence-based frameworks through which we may understand how to approach conflict management: the Thomas-Kilmann model, the DESC model, the LEEN model, and the assertion model.

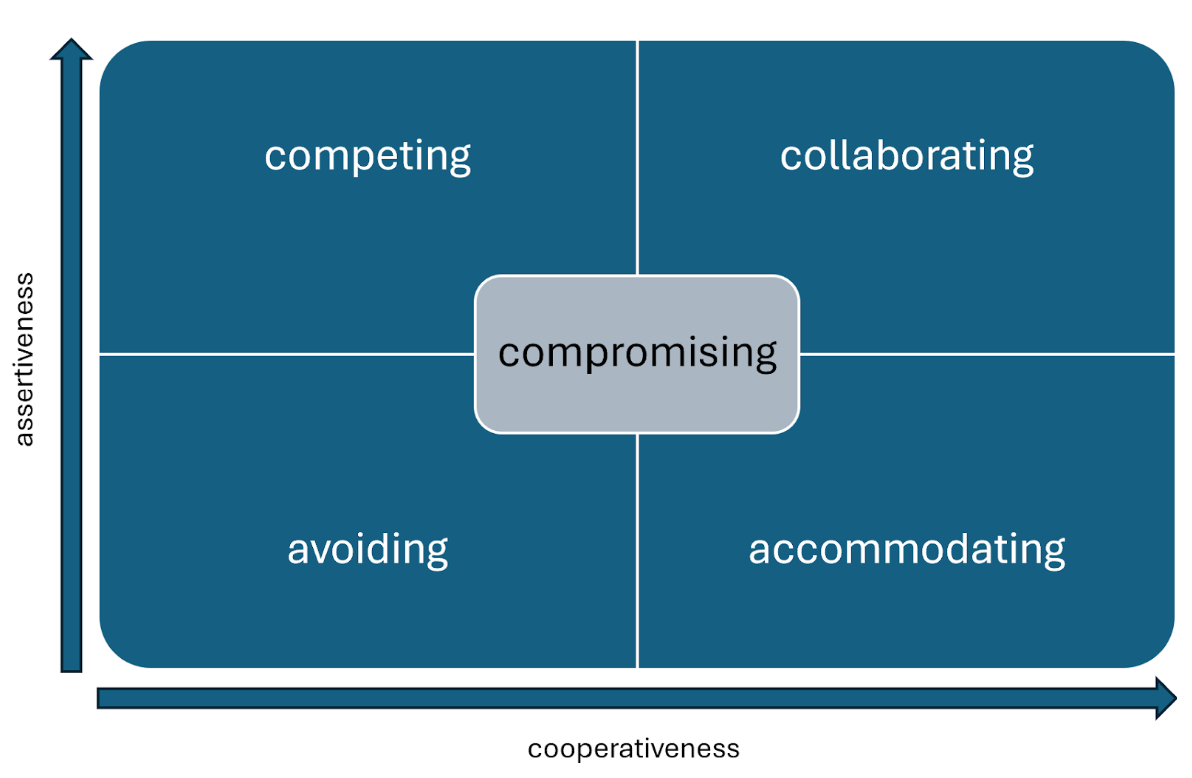

The Thomas-Kilmann model (Figure 1) describes five approaches to conflict management: competing, collaborating, compromising, avoiding, and accommodating.8 These approaches exist on two axes: assertiveness and cooperativeness. Assertiveness is the extent to which one tries to satisfy one’s own concerns, while cooperativeness is the extent to which one tries to satisfy the other party’s concerns. The competitive (i.e., “my way or the highway”) approach may be used when there truly is no room to bargain, but it is one-sided and thus likely to produce resentment and negativity. The collaborative approach seeks to prioritize and preserve the relationship with the other party for further negotiations. The compromising approach is similar to the collaborative approach, but a true middle ground. The avoidant approach ignores the issue altogether, resulting in neither party having their needs met. The accommodating approach results only in the other party having its needs met.

Figure 1. The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

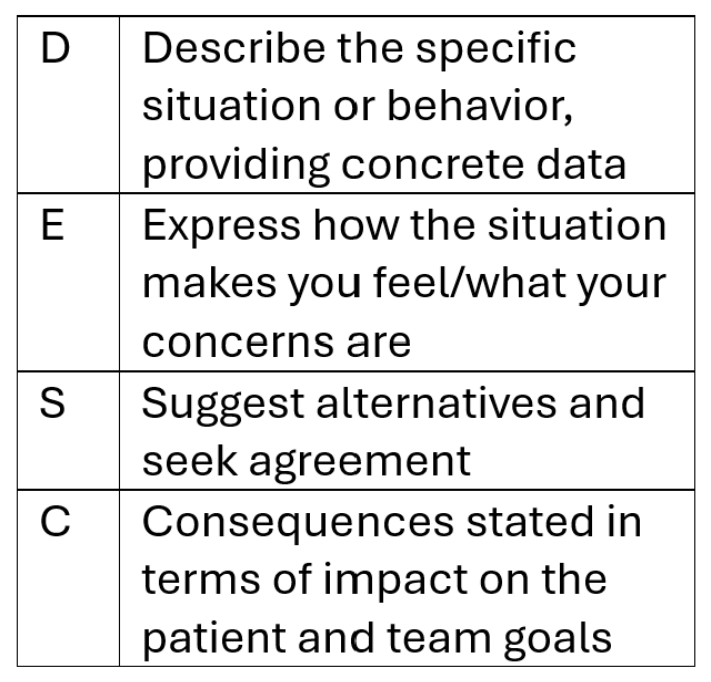

The DESC model (Figure 2), developed by psychologist Sharon Bower and communication expert Gorder Bower, is designed to minimize defensiveness while preserving one’s ability to be assertive.6,9 It is best used in cases of interpersonal conflict and is especially appropriate when a patient’s or team member’s physical or emotional safety is at risk. The four steps of the DESC model are Describe, Express, Suggest, and Consequences. First, the negotiating party describes the issue at hand while taking care to remain objective and fact-based. Next comes an expression of how the situation makes the first party feel. Using “I” statements in this step can help ward off a defensive response. Next, one suggests the desired outcome as well as any acceptable alternatives. Lastly, one states the consequences of that desired outcome as well as the consequences of that outcome not happening. When using this tool, it is important to consider the timing and location of the discussion. Appropriate timing and a private, distraction-free environment can free both parties to focus on the issue and mutually-agreeable solutions rather than being right or avoiding embarrassment.

Figure 2. The DESC tool

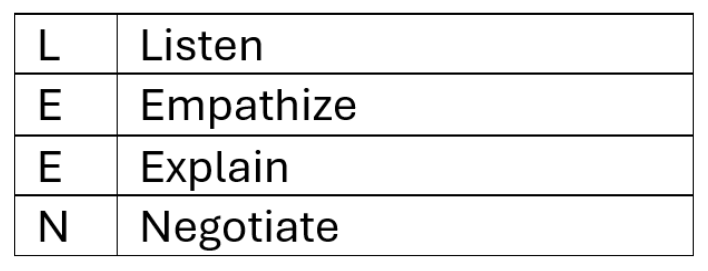

The LEEN model (Figure 3), by contrast, focuses on managing conflict through empathetic listening and negotiation.6 The four steps of this model are Listen, Empathize, Explain, and Negotiate. First, the negotiating party listens to the other party’s concerns. It is important in this step to use active skills such as reflective listening. Next, one makes a concerted attempt to empathize with the other party and his/her point of view. Next comes an explanation of the desired outcome. Lastly, one attempts to negotiate a solution that is agreeable to both parties.

Figure 3. The LEEN model

Modified from: “Conflict Resolution (Slide Presentation).” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Oct. 2011, www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/toolkit/content-calls/conflict-resolution-slides/slides.html.

Lastly, the assertion model (Figure 4) proposes conflict management by delineating one’s priorities respectfully but decisively.6 It is important to be clear about what an assertion is and what it is not. Assertion involves being organized and competent in one’s thoughts and communication to prioritize a common understanding of a problem. It does not involve aggression, confrontation, condescension, or hostility. First, one calls the other party’s attention to the issue at hand. Then, one expresses concern and describes the problem. Next, one proposes an action to address the problem. Lastly, one works with the other party to reach a solution that is acceptable for everyone involved. The keys to utilizing this model well are to focus on the problem rather than the other party and to depersonalize the problem as much as possible to avoid being perceived as judgmental.

Figure 4. The assertion model

Modified from: “Conflict Resolution (Slide Presentation).” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Oct. 2011, www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/toolkit/content-calls/conflict-resolution-slides/slides.html.

What is the two-attempt rule, and what is its relevance in conflict management?

Regardless of the chosen conflict management approach, it is important to keep the two-attempt rule in mind. The two-attempt rule is that one should make a sincere effort to communicate one’s concerns and perspective twice before escalating to a higher authority. This gives the other party two opportunities to engage in a collaborative effort.6

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Mastering the skill of effective and efficient conflict management in healthcare is crucial to maintaining safe patient care, avoiding medical errors/litigation, and optimizing team cohesion and productivity.

- It is important to understand the four evidence-based frameworks for conflict management as well as the optimal contexts in which to use each one.

- The Thomas-Kilmann model, which balances assertiveness and cooperativeness, can be used to address any general conflict.

- The DESC model is optimal in cases of interpersonal conflict.

- The LEEN model relies upon the skills of empathetic listening and negotiation.

- The assertion model, which requires a decisive delineation of one’s goals, is best used when the issue can be depersonalized in an effort to prioritize a common understanding of a problem.

- The two-attempt rule creates an opportunity for collaboration before escalation.

References

- Chan, Teresa, et al. “Conflict Prevention, Conflict Mitigation, and Manifestations of Conflict during Emergency Department Consultations.” Academic Emergency Medicine, vol. 21, no. 3, Mar. 2014, pp. 308–313, https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12325.

- Miner, James R., et al. “Reframing conflict in the Emergency Department as an expected and modifiable source of moral injury.” Academic Emergency Medicine, vol. 31, no. 6, Apr. 2024, pp. 624–625, https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14908.

- Tjan, Timothy Edward, et al. “Conflict in emergency medicine: A systematic review.” Academic Emergency Medicine, vol. 31, no. 6, 28 Feb. 2024, pp. 538–546, https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14874.

- Lewicki RJ, Wiethoff C. Trust, trust development and trust repair. In: M Deutsch, P Coleman, editors. The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory & Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2000, pp 86–107.

- Mayer B. The Dynamics of Conflict Resolution: A Practitioner’s Guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2000.

- “Conflict Resolution (Slide Presentation).” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Oct. 2011, www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/toolkit/content-calls/conflict-resolution-slides/slides.html.

- O’Mara, Karen. “Communication and Conflict Resolution in Emergency Medicine.” Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, vol. 17, no. 2, May 1999, pp. 451–459, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70071-7.

- Kilmann Diagnostics. An Overview of the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) A long-term collaboration by Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann – Kilmann Diagnostics. Kilmann Diagnostics. Published 2025. https://kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki/.

- “Tool: DESC.” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, May 2023, www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/curriculum/mutual/tools/desc.html.