October 07, 2025

3 min read

Key takeaways:

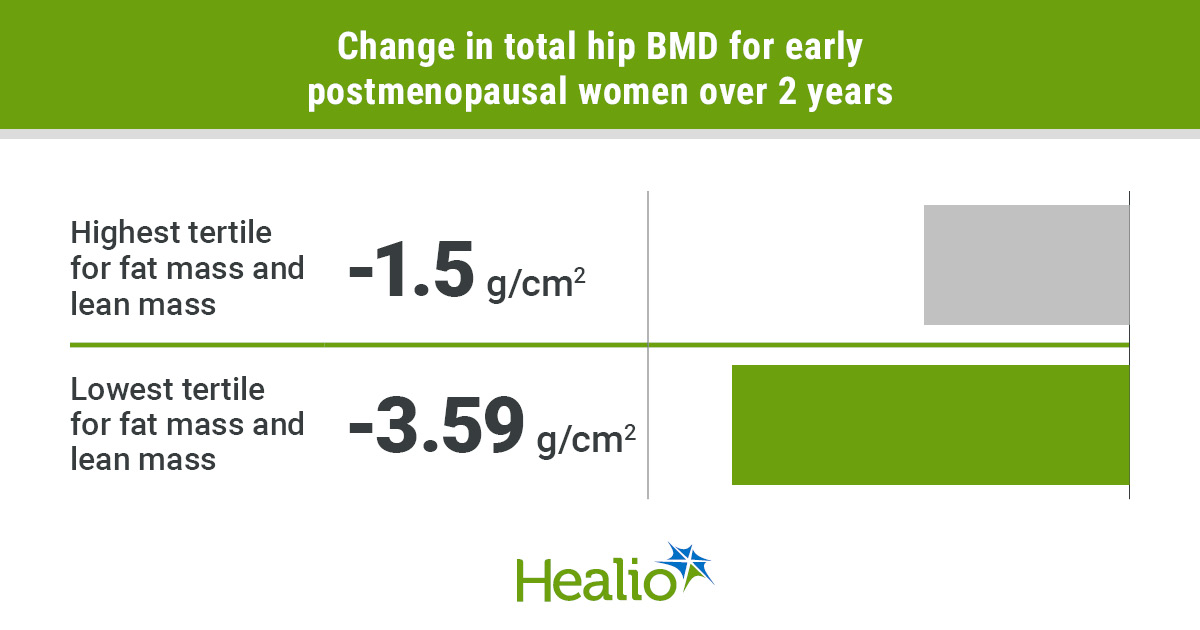

- Higher lean mass during early postmenopause was tied with greater BMD at multiple sites.

- Women in the highest tertile for fat mass and lean mass had less of a decline in bone measures vs. the lowest tertile.

Women who maintain a higher level of lean mass during early postmenopause may have less of a decline in bone mineral density, according to data published in The Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

In an analysis of data from 223 women aged 50 to 60 years in early postmenopause, higher appendicular lean mass over 2 years was tied to higher BMD as assessed by DXA at the total hip and lumbar spine, as well as higher volumetric BMD as assessed by high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT. Additionally, higher BMI and fat mass at baseline were associated with higher total hip BMD.

Data were derived from Geraldi MV, et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2025;doi:10.1093/jbmr/zjaf125.

“We expected lean mass to matter, but the magnitude of the protective association between changes in appendicular lean mass and bone density and microarchitecture over 2 years was notable,” Marina Vilar Geraldi, PhD, postdoctoral researcher, and Mattias Lorentzon, MD, professor of geriatric medicine, both from the Institute of Medicine at University of Gothenburg in Sweden, told Healio. “Also, during this early postmenopausal period, higher fat mass was linked with less BMD loss, underscoring that very low body weight or rapid weight loss can be harmful for bone health.”

Marina Vilar Geraldi

Data were obtained from the ELBOW II trial, a 2-year study conducted in Sweden. Women were enrolled in the study if they had been postmenopausal for 1 to 4 years and had serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels of more than 25 nmol/L at baseline. Follow-up visits were conducted at 1 and 2 years.

Lean mass, fat mass linked to BMD

At baseline, appendicular lean mass, BMI, body weight and fat mass were all linked to higher cortical area, cortical volumetric BMD and total volumetric BMD. Higher weight, BMI and fat mass were also tied to increased total hip BMD at baseline.

Mattias Lorentzon

When time-varying body composition was assessed during the study, higher appendicular lean mass was tied to increased total hip BMD (beta = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.069-0.191; P < .0001), lumbar spine BMD (beta = 0.091; 95% CI, 0.022-0.159; P = .01), total volumetric BMD (beta = 0.058; 95% CI, 0.023-0.094; P = .0015), trabecular bone volume to total volume fraction (beta = 0.048; 95% CI, 0.016-0.08; P = .0038) and cortical area (beta = 0.093; 95% CI, 0.043-0.144; P = .0003). Higher time-varying fat mass during the 2-year study was linked to increased cortical area (beta = 0.056; 95% CI, 0.002-0.11; P = .042).

Researchers grouped women into tertiles based on baseline fat mass and change in appendicular lean mass during the study. The first group included women in the lowest tertile for both baseline fat mass and change in appendicular lean mass (n = 28), the second group included women in the highest tertile for both measures (n = 28) and the third group included all other participants (n = 154).

Women in the highest tertile for both fat mass and lean mass had less of a decline in total hip BMD (mean change, –1.5 g/cm2 vs. –3.59 g/cm2; P = .004), tibia total volumetric BMD (mean change, –0.64 mg/cm3 vs. –3.33 mg/cm3; P < .001), tibia trabecular bone volume to total volume fraction (mean change, 0.26 percentage points vs. –2.05 percentage points; P = .002) and tibia cortical area (mean change, –1.19 mm2 vs. –4.59 mm2; P = .004) than women in the lowest tertile in both measures.

Tips for maintaining lean mass

Geraldi and Lorentzon said postmenopausal women should focus on resistance training and eating adequate amounts of protein to maintain lean mass. They added that special considerations are needed for women who need to lose weight during postmenopause.

“When weight reduction is medically indicated, it should be paired with resistance training and sufficient protein intake to minimize lean loss,” Geraldi and Lorentzon said. “In women with osteopenia or osteoporosis, this requires particularly careful consideration.”

According to Geraldi and Lorentzon, longer-term studies are needed to examine how body composition changes may impact BMD and incident fracture risks, as well as how changes in physical activity, diet and gut microbiota impact bone outcomes.

For more information:

Marina Vilar Geraldi, PhD, can be reached at marina.vilar.geraldi@gu.se.

Mattias Lorentzon, MD, can be reached at mattias.lorentzon@medic.gu.se.