[ad_1]

October 13, 2025

5 min read

Key takeaways:

- 22% of patients with inpatient care for more than a year had an IDD.

- Long-stay patients with IDD had more outpatient psychiatry and ED visits.

- 5.3% of patients with IDD were in units specialized for their care.

More than one in five patients occupying a psychiatric inpatient bed in Ontario for a year or longer had an intellectual or developmental disability, according to data published in The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry.

These patients may need more support from the hospital and community to facilitate their transition from care, Avra Selick, PhD, scientist, Azrieli Adult Neurodevelopmental Centre, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, and colleagues wrote.

Data derived from Selick A, et al. Can J Psychiatry. 2025;doi:10.1177/07067437251380731.

“We know from prior work our team has done that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs) are more likely to be hospitalized and stay in the hospital longer,” Selick told Healio.

Avra Selick

However, Selick said that she and her colleagues did not have total numbers for occupied psychiatric hospital beds in Ontario, which stakeholders could use in system planning and in efforts to transition these patients out of these hospitals.

“Most people underestimate the true number of individuals with IDD who have been in the hospital for a long time,” she said. “Therefore, we often don’t have enough resources or the right resources to support them in hospital and support their transition to the community.”

This lack of data prompted the study, Selick said.

Current occupancy

The population-based, cross-sectional study found 4,687 adults in non-forensic psychiatric inpatient beds in Ontario across general hospitals and provincial and specialty psychiatric facilities as of Sept. 30, 2023.

“Most people aren’t aware of just how many patients with IDD are currently in hospitals and have sometimes been there for a very long time,” Selick said.

This cohort included 19.9% with an IDD, including intellectual disability, autism, other pervasive developmental disorders, fetal alcohol syndrome and various chromosomal disorders. Also, 1,466 of the full cohort had been in the hospital for a year or longer, and 322 (22%) had an IDD.

“On average, the patients in both of these groups — with and without an IDD — had been there for 5 years, some of them for over 20 years,” Selick said.

The overall median length of stay was 3 years, with a mean of 4.7 years for the group with IDD and 5 years for the group with no IDD.

Patients with IDD in the long-stay group had a mean age of 44.3 years, compared with 47.6 years among those with no IDD, and 64.3% were male, compared with 50.1% among those with no IDD. The long-stay IDD group included 125 (38.8%) with autism as well.

Percentages of patients diagnosed with a psychotic disorder in the 2 years before admission in the long-stay group included 73.3% of those with an IDD and 54% of those with no IDD.

With mean numbers of outpatient psychiatry visits including three for the IDD group and one for the group with no IDD and median numbers of ED visits including five for the IDD group and three for the group with no IDD, the researchers said both groups were likely to have used health care services in the 2 years before admission.

The researchers also noted that admission due to a threat to others or inability in self-care was more likely among the IDD group and that admission due to a threat to self was more likely among the group with no IDD.

Among the group with IDD, 5.3% were in specialized units for patients with IDD, 41% were in acute units, 32.3% were in longer-term units and 6.5% were in geriatric units.

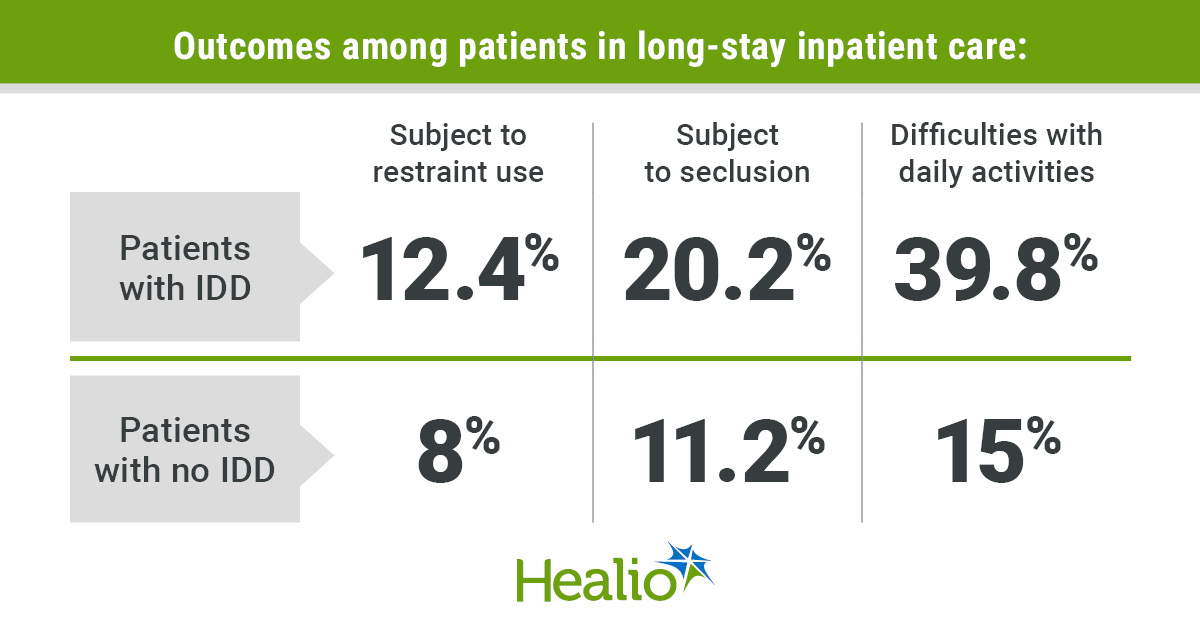

Percentages of patients subjected to restraint use included 12.4% of the IDD group and 8% of the group with no IDD. Percentages of patients subjected to seclusion included 20.2% of the IDD group and 11.2% of the group with no IDD.

Compared with the group with no IDD, the group with IDD also was more likely to have difficulties with daily activities (39.8% vs. 15%), severe cognitive impairment (29.5% vs. 9.6%) and fewer social contacts who could support discharge (59.3% vs. 48.6%).

Impact on patients

Considering these findings, Selick and colleagues said that policies and practices to support long-stay patients are not designed for patients with IDD, who also require community and social services support to transition successfully from inpatient care.

“A hospital is not a home. No one should be living in the hospital for decades,” Selick said. “Also, it is extremely costly to keep people in hospital. Ethically and financially, the current situation cannot and should not be sustained.”

Further, the researchers noted that securing support may be difficult for these patients, who may be staying in the hospital even though they no longer need care because they would lack that support once they leave.

“Patients with IDD have important differences from other patients and therefore often require different supports to ensure they receive appropriate care in hospital, to help them transition successfully into the community and to prevent unnecessary hospitalizations in the first place,” Selick said.

Care for long-stay patients often focuses on transitions to long-term care, she continued, although such facilities may not be a good fit for patients with IDD who typically are younger and need support from the disability sector.

“Though there are fantastic individuals working hard to support this population, hospitals and communities do not consistently have access to the resources and skilled professionals necessary to support people with IDD and their families,” Selick said.

There is a need to build these resources in the health and developmental services sectors, she said, while helping these sectors collaborate in supporting these patients.

Considering the 5.6% of patients with IDD who were in units designed for their needs, the researchers said these long stays may be due to a lack of appropriate care during their inpatient experience.

Appropriate care requires training specific for this population, which many personnel lack, leading to mental health conditions attributed to the patient’s disability or the disability being overlooked.

Inpatient units that do not specialize in patients with IDD also may lack staff from a range of related disciplines such as occupational, speech and language therapy. Environments may not be sensory-friendly as well, with fluorescent lighting, disturbing noises and smells, and difficult roommates.

These inconsistencies in meeting the needs of patients with IDD may in turn drive greater use of medication, restraints and seclusion, additionally making the transition out of the hospital more difficult.

Selick and colleagues recommended increased inpatient and outpatient capacity for treating patients with IDD, with more staff trained in their care, using consultation models when expertise is needed, and increased access to specialized services.

Upstream prevention also may mitigate these burdens, the researchers said, by focusing on patients with high levels of health care utilization and enhancing the community support they can receive before they require long-stay admission.

“This feels like a really big challenge, but solutions are possible,” Selick said.

Selick noted that Ontario Practice Guidance details how long-stay patients with IDD can be transitioned from hospital care successfully, with “great” examples that providers can learn from.

“We know that key to successful transitions is ensuring hospitals have access to skilled providers with expertise in IDD, building partnerships between the health and developmental services sectors, including patients and families in the transition planning process, and ensuring we have the community resources in place necessary for people with IDD to live successfully in the community, including housing, mental health care and primary care,” she said.

The research is continuing, Selick added.

“We are continuing to use health administrative data at [the Institute for Clinical and Evaluative Sciences] to better understand this patient group, including how they end up hospitalized in the first place and their trajectory post discharge,” she said.

[ad_2]

Source link