Adding a phosphate group to a protein—a process called phosphorylation—is a key way cells control important activities like –

- sending signals,

- breaking down food for energy (metabolism),

- cell growth, and

- programmed cell death (apoptosis).

The process happens after the protein is made. Special enzymes called protein kinases add a phosphate group to specific parts of the protein, typically to the amino acids serine, threonine, or tyrosine.

Another group of enzymes, called phosphatases, can remove these phosphate groups.

To check if a protein is phosphorylated, scientists often use a method called Western blotting. While the basic steps of a Western blot are the same, detecting phosphorylated proteins can require some special attention to get the best results.

One important step is to buy phospho-specific antibodies. However, choose the ones that are designed to detect only the phosphorylated version of your protein. These antibodies help make sure you’re seeing the correct signal in your experiment.

1. Know when your protein gets phosphorylated

Proteins are not always phosphorylated—they often become phosphorylated only under certain conditions.

| For example, it might occur when cells are exposed to a specific signal, during disease, or after treatment with certain chemicals. |

To figure out when your protein of interest is phosphorylated, it’s important to read scientific studies about it. This will help you know what conditions to use in your experiments to detect its phosphorylated form.

If your cells need a specific treatment to trigger phosphorylation, it’s a good idea to test different treatment levels and times. Doing a time-course experiment can show you how long the phosphorylation lasts, so you can choose the best time to collect your samples.

| Example: Western blotting was used to detect phosphorylated MEK1 (at position Thr386) in HeLa cells, both untreated and treated with Calyculin A. The blot was then stripped and re-used to check GAPDH levels as a loading control. Another example showed detection of phosphorylated TDP43 (at positions Ser409/Ser410) in untreated HeLa cells and those treated with ethacrynic acid (150 µM for 5 hours), with GAPDH used again as a control. |

2. Protect your phosphorylated proteins

When you break open cells to collect protein (a step called lysis), natural enzymes called phosphatases are released.

These enzymes can quickly remove phosphate groups from your proteins, which would mess up your experiment. To stop this from happening –

- Always add phosphatase inhibitors to your lysis buffer.

- Also, include protease inhibitors to stop other enzymes from breaking down your proteins.

- Once the proteins are collected, quickly mix them with SDS sample buffer. These help stop enzyme activity and keep your proteins in good shape for storage.

3. Choose the right blocking solution

Blocking is a key step in Western blotting. It stops antibodies from sticking to the membrane in the wrong places.

Usually, people use 5% non-fat milk for blocking because it’s cheap and easy to find. But milk contains casein, a phosphorylated protein that can be mistakenly detected by anti-phospho antibodies, causing high background signals.

If you’re getting high background with milk, try using BSA (bovine serum albumin) instead, which doesn’t have phosphoproteins.

4. Don’t use phosphate-based buffers

Some buffers, like PBS (phosphate-buffered saline), contain phosphate, which can interfere with anti-phospho antibodies and reduce their ability to detect your target protein. To avoid this –

- Use Tris-based buffers like TBST (Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20) for Western blot steps.

- If you must use PBS in some parts of your experiment, be sure to wash the membrane well with TBST before adding antibodies.

5. Use antibodies that specifically detect phosphorylated proteins

Make sure the antibodies you use are made to recognize only the phosphorylated form of the protein, not the regular (non-phosphorylated) version.

If the antibody isn’t specific, it may detect both forms, making your results unclear or misleading.

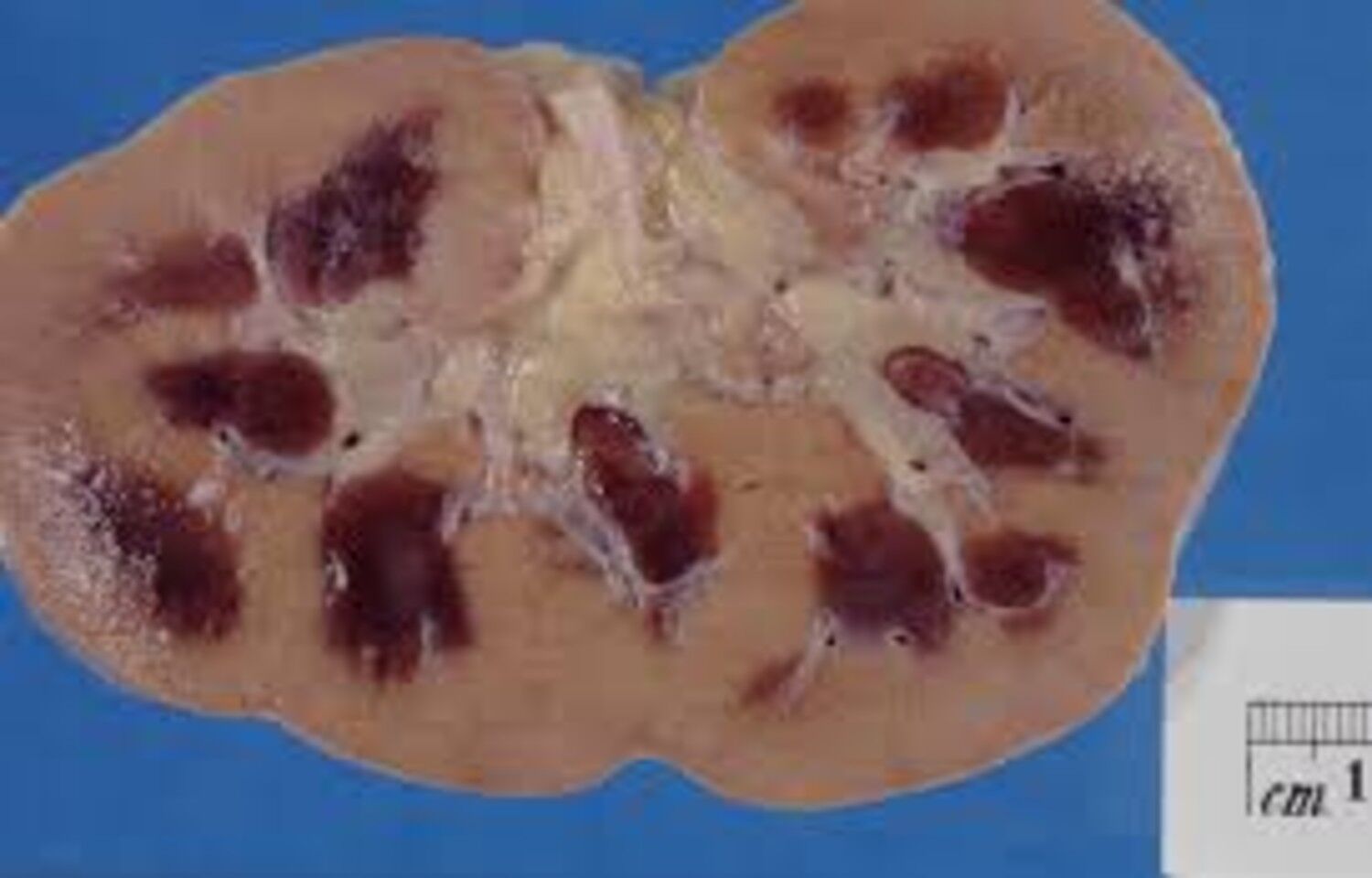

It is especially important in research involving complex samples, such as those from infectious disease models like Mouse Malaria Plasmodium Lactate Dehydrogenase, where precise detection of modified proteins is critical for understanding disease mechanisms.

6. Check total protein levels

The amount of phosphorylated protein you detect can change for many reasons—like how cells are treated or if you accidentally load different amounts of protein in each sample.

To help with this, also check for the total amount of the protein (phosphorylated + non-phosphorylated). It acts as a control and helps you figure out what percentage of the protein is actually phosphorylated.

When doing this, use PVDF membranes instead of nitrocellulose—they’re stronger and better for stripping and reusing the membrane.

| Example: Western blot showed levels of phosphorylated mTOR (Ser2448) in untreated and rapamycin-treated cells. Then the membrane was stripped and tested again to check for total mTOR and another protein, RICTOR. |

7. Use proper controls

Always include control samples in your experiment:

- A positive control where you expect the protein to be phosphorylated.

- A negative control where the protein should not be phosphorylated.

You can also treat your samples with phosphatases (enzymes that remove phosphate groups).

If the band disappears after treatment, it confirms that your original band was truly the phosphorylated protein.

| Example: In one test, cells treated with a phosphatase inhibitor showed more phospho-Cofilin, while cells treated with phosphatase had no detectable phospho-Cofilin. |

8. How to detect phosphoproteins present in small amounts

Phosphorylated proteins often make up only a tiny part of the total protein. This makes them harder to detect. Here’s how to improve the signal:

- Load more protein onto the gel by using less lysis buffer when preparing your samples.

- Use a high-sensitivity detection method (like enhanced chemiluminescence).

- Enrich your sample by pulling out the phosphoprotein first using immunoprecipitation before Western blotting.

- Make sure the cells were properly treated to stimulate phosphorylation (refer back to Tip #1).

9. Use fluorescent detection to measure both forms at once

Stripping and reusing membranes to measure both total and phosphorylated proteins can damage the sample.

Instead, use fluorescent Western blotting, which lets you detect both at the same time—without stripping.

To do this:

Use two different antibodies (each from a different species) –

- one for the phosphorylated form and

- One for the total protein.

Use fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies to detect each one.

The method gives cleaner results and more accurate comparisons.

Image by Google DeepMind from Unsplash

The editorial staff of Medical News Bulletin had no role in the preparation of this post. The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the advertiser and do not reflect those of Medical News Bulletin. Medical News Bulletin does not accept liability for any loss or damages caused by the use of any products or services, nor do we endorse any products, services, or links in our Sponsored Articles.