What was it?

Multicenter, randomized, open-label trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of intravenous rehydration in children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and gastroenteritis, comparing low-volume rehydration (World Health Organization [WHO] standard) with higher-volume rehydration protocols.

The Devil in the Details!

- 272 children analyzed across 4 countries in Africa

- Three arms: WHO standard (low-volume, 100 mL/kg over 12 hours), moderate-volume (150 mL/kg), and high-volume (200 mL/kg) rehydration with Ringer’s lactate or half-strength Darrow’s solution.

- Children aged 6 months to 12 years with SAM (mid-upper arm circumference <11.5 cm or weight-for-height Z-score <-3) and acute gastroenteritis with dehydration.

- Primary outcome: Proportion of children with correction of dehydration at 4 hours (clinical assessment).

- Secondary outcomes: Time to full rehydration, mortality, adverse events (e.g., fluid overload, electrolyte imbalances).

- Open-label design due to logistical constraints in blinding fluid volumes.

The Results!

- Correction of dehydration at 4 hours: 60% in WHO standard, 68% in moderate-volume, and 72% in high-volume arms (p=0.35, not statistically significant).

- Participants were followed for 28 days.

- A nasogastric tube was used for oral rehydration in 126 of 135 participants

- (93%) in the oral group

- (65%) in the intravenous groups.

- Intravenous boluses were administered at admission in 12 participants

- (9%) in the oral group

- (10%) in the rapid intravenous group

- none in the slow intravenous group.

- At 96 hours, death occurred in

- (8%) in the oral group

- (7%) in the intravenous groups (5 in the rapid group and 4 in the slow group)

- At 28 days, death occurred in

- (12%) in the oral group

- (10%) in the intravenous groups

- Serious adverse events occurred in

- (23%) in the oral group

- (21%) in the rapid intravenous group

- (15%) in the slow intravenous group.

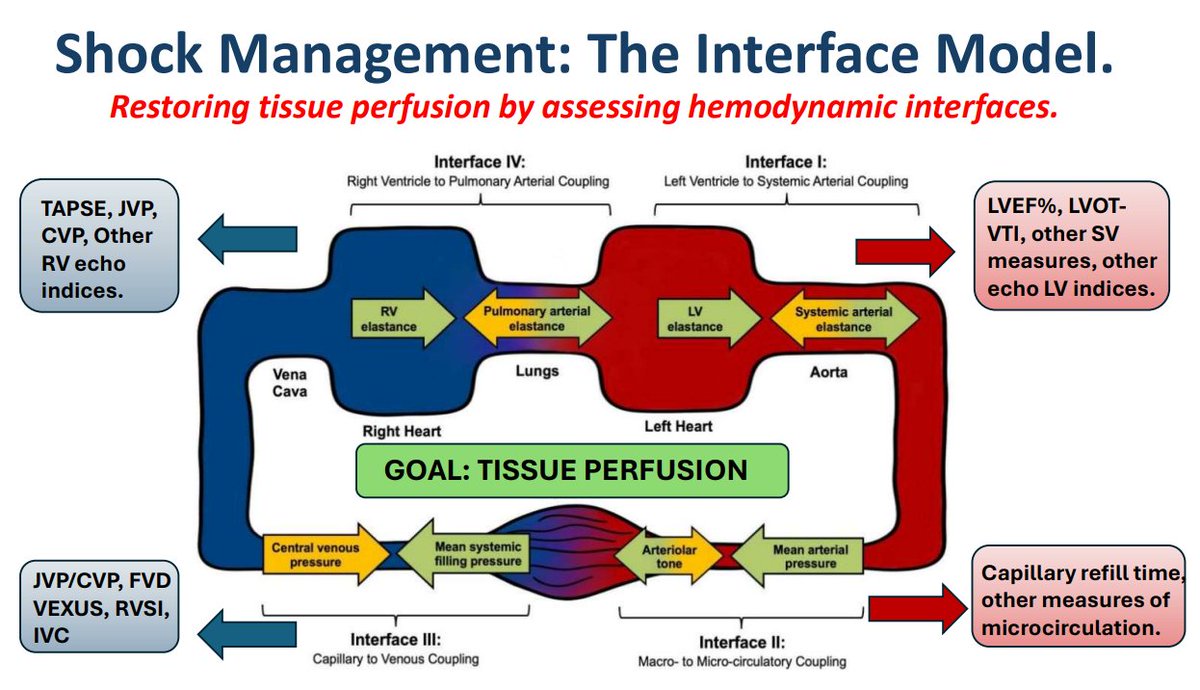

- No evidence of pulmonary edema, heart failure, or fluid overload was noted.

- Median time to full rehydration: 6 hours (WHO), 5 hours (moderate), and 4.5 hours (high) (p=0.12).

- Mortality: 12% (WHO), 10% (moderate), 8% (high) (p=0.67).

They concluded

The authors concluded that higher-volume intravenous rehydration in children with SAM and gastroenteritis may lead to faster correction of dehydration compared to WHO standard, without significantly increased risk of fluid overload, but larger trials are needed to confirm efficacy and safety.

Gripe Point Summary!

Detailed gripes below, but in short:

- Open-label design introduces bias in clinical assessments.

- Small sample size limits power for mortality and safety outcomes.

- Clinical dehydration assessment lacks objectivity.

- Heterogeneity in fluid types (Ringer’s vs. half-strength Darrow’s) confounds results.

- Limited generalizability to non-specialized settings.

- Short follow-up period misses long-term outcomes.

- High baseline mortality reflects population severity, complicating interpretation.

- No adjustment for multiple comparisons in secondary outcomes.

Our Summary

In children with SAM and gastroenteritis, higher-volume intravenous rehydration (150–200 mL/kg) showed a trend toward faster dehydration correction compared to WHO standard (100 mL/kg), with no significant increase in serious adverse events. However, the open-label design, small sample size, and lack of objective outcome measures limit confidence. This trial suggests potential for revising WHO guidelines but calls for larger, blinded studies.

Who’s worked on this before?

Further gripes

- Open-label design: Unblinded clinicians assessing dehydration status could bias results, especially for subjective clinical signs (e.g., skin turgor, sunken eyes).

- Small sample size: 122 patients across three arms (roughly 40 per arm) underpowered to detect differences in mortality or rare adverse events like pulmonary edema.

- Subjective primary outcome: Clinical assessment of dehydration lacks standardization and precision compared to objective measures (e.g., weight gain, urine output).

- Fluid type variability: Use of Ringer’s lactate or half-strength Darrow’s solution introduces heterogeneity, as electrolyte composition differs, potentially affecting outcomes.

- Limited generalizability: Conducted in specialized hospitals with trained staff; results may not apply to resource-poor settings where SAM is prevalent.

- Short follow-up: Outcomes assessed up to 48 hours; long-term effects (e.g., renal function, nutritional recovery) unknown.

- High baseline mortality: 8–12% mortality reflects severe illness but complicates interpretation of intervention effects.

- No statistical adjustment: Multiple secondary outcomes (e.g., time to rehydration, adverse events) analyzed without correction for multiple comparisons, increasing risk of false positives.

- Exclusion criteria: Excluded children with shock or severe electrolyte imbalances, limiting applicability to the sickest patients.

- Fluid overload trend: 10% incidence in high-volume arm raises safety concerns, despite not reaching statistical significance.

- No data on non-pharmacological factors: Nutritional support or antibiotic use not standardized, potentially confounding outcomes.

- Feasibility concerns: Higher-volume protocols require close monitoring, which may be impractical in low-resource settings.

CCN’s Reflection

This trial tackles a critical question in managing SAM with gastroenteritis, challenging WHO’s conservative rehydration guidelines. The trend toward faster rehydration with higher volumes is intriguing, but the open-label design and small sample size undermine confidence. The lack of objective outcome measures and high baseline mortality further muddy the waters. While the study hints at a need to rethink fluid strategies, it’s far from a game-changer. We need larger, blinded, multicenter trials with standardized protocols and longer follow-up to settle this debate. Until then, stick to WHO guidelines unless you’re in a well-monitored setting ready to watch for fluid overload.

Written by JW