Excerpt from “Lent: Grief and the Renewal of All Things” by Curt Thompson, MD.

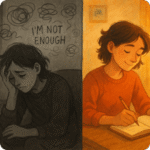

As I have been reflecting on and anticipating this season in the Church calendar, it occurred to me how beautifully and mysteriously our observance of Lent maps on to our day-to-day experiences, as well as the whole of our lives. Not least in terms of how it connects us not only to our sin, but to our grief. And as it turns out, it is to our grief we must go if it is liberation from our sin that we desire.

Just as it was for the first couple on the third page of the Bible, our deepest longings—to be seen, soothed, safe, and secure; to be deeply known and loved such that we can in turn joyfully create and curate beauty and goodness in the world—are ultimately realized in the context of intimate relationships of lovingkindness.

But like the first humans, it is those very relationships that are responsible for the wounds that lead to our coping behavior, our sin.

Therefore, as much as Lent is about confronting our sin, it is also for the purpose of addressing and acquiring comfort for our grief. For indeed, naming our sin requires that we eventually name our griefs as well.

It is in naming them both in a community that responds with mercy—yet not without demands—that we are able to address how our sin (our misdirected desire) has hurt everyone: others, ourselves, and perhaps God not the least.

But naming our sin and grief is not for the sake of having those we have hurt shame us. That is not the business God is in. Rather we name our griefs such that others can remind us of the forgiveness that in Jesus is—as it has always been—waiting for us to receive it. In our receptivity to his love via the love of his body of followers, we can turn and begin to name, perhaps for the first time, what we most truly desire—to be known in order to create beauty and goodness in the world—and thus live into that very vision.

What makes this whole enterprise of naming our griefs so difficult, however, is at least twofold.

First, the memory of our grief is frequently so painful, and therefore something we naturally avoid. The extent of our grief is so vast.

We live with brains that carry with them the memories of trauma and grief that are held in older neural networks. This means that, despite working toward genuine healing, those older networks can be activated when we find ourselves under particularly unpredictable and deeply stressful circumstances.

The challenge for us is when we encounter the right set of wrong circumstances, and those older networks that represent our grief once again temporarily take center stage of our experience. Our minds are aware of this possibility, even after long periods of growth. Hence, at times the anticipation of encountering intimate relationships for the purpose of healing can tend to harken the memory of how intimacy has been the very source of our grief in the first place.

For many of us, then, visiting the rooms where our grief resides can be unsettling at best, frightening at worst. This is why the process often requires a slow, deliberate approach to those rooms in the presence of other fellow pilgrims or friends:

- Friends who are willing to remain with us every step of the way.

- Friends who will be the faithful presence of Jesus when we open the door to the rooms that hold our histories of suffering—suffering that has been foisted upon us, and suffering that we have foisted upon ourselves.

- Friends who will beckon us to pay more attention to the love they are offering to us in the presence of our grief as we are in the very middle of it.

- Friends who help us learn that our grief, though real, is no longer something we need to fear remembering.

- Friends who, like Jesus, will not leave us or forsake us.

Second, the process of encountering our grief is difficult because of just how much of it there is. We wildly underestimate how much grief we carry, and we do so for good reason: to pay attention to it can begin to feel overwhelming.

To do this, we distract ourselves, and there is no end to the things at our disposal to do that very thing. From our devices to our work to our leisure, we have many opportunities that provide the entertainment that will keep us from visiting our souls, and keep us from the rooms where our grief resides. Until, of course, our distractions are no longer able to keep our grief at bay. And this, despite how overwhelming at first glance it might be to come to terms with, reveals how great the acreage is in our minds that it actually occupies.

It is for both of these reasons that Lent is so important.

Lent is not a one day deal. Christmas and Easter are one day deals. Lent, not so.

For indeed we are born into the world in a moment, as was Jesus. And we are told that resurrection will happen in the twinkle of an eye.

But confession? The healing of grief? The learning to fast from our idols long enough to give God time to feed us from the Tree of Life? All of this takes a lifetime, which is a good thing. Because to practice overcoming the memory of shame, and to explore our grief to the depth it exists will take a long, long time.

With Lent, we are given the opportunity to take our time—time that God is more than happy to share with us, for indeed, he is not in a rush. He is too busy wanting to make sure that we leave no stone of shame or grief in our story unturned, such that every square inch of our story that lies beneath it will come to know what it means to be loved. We are loved in such a way that the deep longing that preceded any sin that is concealed there will itself be renewed and recommissioned.

As we begin the Lenten season, looking forward to Easter, may we with comfort and confidence—if even accompanied by the fear of our memories—name our sin, such that we may even more so enter the rooms of our grief, and hear our King and our brothers and sisters alike, as was true for Lazarus, call to what lies there, “Come out!” so that the mourning of our grief may be transformed into the dancing of joy.

Cover photo by mali desha on Unsplash

Curt Thompson, MD

Curt Thompson, MD, is a board certified psychiatrist, author, speaker, and co-host of The Being Known Podcast. He has been in private practice for over 30 years in Falls Church, Virginia, graduated from Wright State University’s Boonshoft School of Medicine, and completed his psychiatric residency at Temple University Hospital. He strives to help patients develop flourishing lives by telling their stories more truly, in order to become more deeply known, for the purpose of creating beauty and goodness in the world. With conviction and humour, he trains clinicians and speaks at workshops, retreats and conferences, integrating neuroscience, human relationships and Christian faith. He and his wife Phyllis are the parents of two adult children and live in Northern Virginia.