So I read a publication called the Expert Witness Newsletter on Substack. The anonymous author publishes case transcripts from actual malpractice cases and then weighs in with his perspective–quite a good read! He recently documented a case of missed PE in which the doc lost with a $10 million dollar verdict. The case was a little anger producing, but then in a unique circumstance, the jury foreman actually wrote in with additional perspective.

In today’s episode, I interview the anonymous MedMalReviewer and we discuss the case. It will be relevant and informative even if you are outside the USA.

Case taken the the Expert Witness Substack

Link to the Substack Post

A 21-year-old college student went to the ED for cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath.

He had been diagnosed with COVID at an urgent care 3 days earlier.

An EKG was done.

The ED note is shown below:

The patient returned home.

Over the next week he continued to have symptoms.

A week after the ED visit, he had a syncopal episode while running up stairs.

EMS was called but he declined transport to the hospital.

The patient’s friends would later claim that the EMS crew told him he would be fine and pressured him to sign the refusal form.

6 days after the EMS visit, the patient had a cardiac arrest.

EMS obtained ROSC and he was taken to the ED.

The patient was diagnosed with massive pulmonary emboli and admitted to the ICU.

Neurologic function did not return.

He died 5 days after the cardiac arrest.

The patient’s parents filed a lawsuit against the ED physician and hospital.

They did not sue the urgent care nor the EMS service.

Multiple expert witnesses were hired including ED, cardiology, and hematology.

The only written expert report included in the court records was a hematologist for the defense.

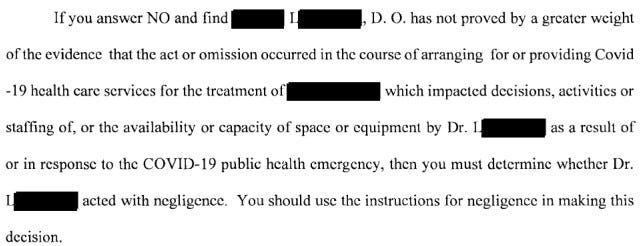

The state in which this happened had a COVID-19 Limited Liability Act that was in force at the time of this case.

The relevant part of the law is shown below.

The defense felt that the Limited Liability Act applied to this case, and asked that the lawsuit be thrown out.

The plaintiff felt that the pandemic did not influence the testing that could have been done, and therefore the law did not apply to this case.

The plaintiff’s attorneys cited the criticisms made by their experts in order to build an argument that the failure to order additional testing after reviewing the EKG met the definition of gross negligence.

Gross negligence has been defined in this state’s law and by their Supreme Court in various ways:

- “the want [lack] of slight care and diligence”

- conduct that is “so flagrant, so deliberate, or so reckless that it is removed from the realm of mere negligence.”

- “reckless indifference to the consequences”

The judge refused to throw the lawsuit out, and decided it would be up to the jury to decide if the Limited Liability Act would apply in this case.

The two sides were unable to reach a settlement before trial.

The jury decided that the Limited Liability Act did not apply in this case.

Therefore, they used an ordinary negligence standard, not gross negligence.

They returned a $10,000,000 verdict against the doctor and hospital.

They assigned 25% of the blame to the deceased patient.

One unique aspect of this case is that this jurisdiction uses a “modified comparative negligence” standard (aka 51% bar rule).

If the patient is determined to have 51% or higher contributory negligence, the plaintiff doesn’t recover anything.

Since the patient in this case was found to be 25% responsible, both the doctor and hospital are responsible for their assigned share of the damages.

Many decades ago, most states had “pure contributory negligence” meaning that if a patient was found to be even 1% responsible, the plaintiff could not recover anything.

Almost all states have now switched to comparative negligence, whereby each defendant is responsible for their percentage of liability, even if the patient was also found to be negligent.

The verdict is currently being appealed.

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

- This case is an undeniable tragedy. I watched a memorial video made by the patient’s mother and it was heart-wrenching. That being said, a medical malpractice lawsuit should not be decided based on emotion. In my opinion, it was reasonable for the doctor to attribute cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath to COVID. The patient did not have any of the usual findings that would suggest PE such as tachycardia, hypoxia, or leg swelling, and did not report any PE risk factors (although may have had a family history of antithrombin III deficiency that was unreported). If there is concern for PE, the appropriate workup starts with risk stratification (Wells, modified Geneva, or clinician gestalt). This patient’s modified Geneva score is zero, and therefore he is low risk for PE. Low risk patients are eligible for PERC. This patient “PERCs out” and therefore there is no indication for d-dimer or CT. The doctor didn’t document this thought process, but the fact remains that he followed the appropriate workup and met the standard of care.

- The key issue in this case was whether the EKG should have triggered further workup despite his PERC-negative status. The doctor described the EKG as “nonspecific ST changes”. When I looked at it I noticed the inverted T waves in chest leads and inferiorly, but did not understand the significance of this pattern. After doing a lot of reading, I now feel that the key learning point from this case is recognizing that simultaneous T-wave inversions in V1 and III is associated with PE. The best articles about this pattern come from Dr. Smith’s ECG blog, where he cites 2 papers by Kosuge and Witting.

- Kosuge wrote the original paper that described this association. They looked at patients with inverted precordial T waves who were ultimately diagnosed with PE or ACS. They found that a negative T wave in both V1 and III is highly suggestive of PE as opposed to ACS. Only 1% of patients with ACS had this finding, versus 88% of PE patients. They only looked at patients who had TWI in precordial leads AND were subsequently diagnosed with ACS or PE (among some other criteria that are beyond the scope of this blog) so this does not necessarily generalize to undifferentiated ED patients, but the fact that it had such strong test characteristics (97% PPV and 95% NPV) means you shouldn’t ignore this.

- Witting did a study that is a better reflection of undifferentiated ED patients, looking at patients that were ultimately diagnosed with PE, ACS, or non-cardiac chest pain. They found >1mm T-wave inversions in both V1 and III in 11.3% of PE patients, 4.5% of ACS patients, and 4.8% of non-cardiac chest pain patients. These results reflect a much greater degree of ambiguity than the Kosuge study and explain why this EKG finding may not raise alarm bells in the real world. However, they found that >2mm TWI in V1, V2, III, aVF were found in 4% of PE cases, but was never found in patients with ACS or non-cardiac chest pain. I was fairly surprised to find this buried in Table 1 because the classical teaching is that there are no EKG findings that are pathognomonic for PE. And yet, this paper suggests that this long-held dogma is incorrect and there may actually be a pathognomonic EKG finding for PE (>2mm TWI in all 4 of these leads). I’m not quite willing to make a claim this bold (after all, only 4 patients met this criteria) but I think it deserves more publicity than it has gotten. Notably, I think the EKG in this case reflects this potentially-pathognomonic finding. The millimeter markings were lost on the court copy and it’s very close to being 2mm in aVF, but I think it’s there.

- Steve Smith’s ECG blog has published tons of real-life cases about this exact same pattern (TWI in V1 and III indicating PE). They’re a bit easier to read than the 2 research papers above. I strongly recommend that you read this case from his blog and look through the links at the bottom… there’s over 20 PE cases that have this pattern. Note that while TWI in V1 and III raises the possibility that there may be a PE, it can also be found in patients who are hypoxic or have other respiratory pathology.

- I’m sure that a few astute readers are familiar with this pattern, but I doubt the majority of doctors are familiar with it’s specific description and association with PE. It was first described in 2006 and is slowly gaining more attention. I think any of us would be very worried about this EKG if it was an elderly patient with acute chest pain and history of coronary artery disease, but in a young man with COVID, I can see how it might not prompt further workup. Furthermore, the patient did not have the more commonly taught EKG findings including sinus tachycardia or S1Q3T3.

- This is the benefit of reviewing med mal cases… it allows us to hammer home rare learning pearls in a way that is absolutely unforgettable. If you read about this topic in a boring journal article, you’ll probably forget it. If you read about it in the context of a dead college student and a doctor who lost a $10,000,000 verdict, it’s unforgettable.

- With the benefit of hindsight, there are 2 other issues that could have raised concern and triggered a bigger workup:

- The timeline didn’t make sense for COVID. The patient described 2 weeks of symptoms of cough and congestion. However, it wasn’t until the last few days that he developed shortness of breath with exertion and chest pain. These new symptoms represent a departure from the expected clinical COVID course. I would expect a healthy young man to be feeling better by that point, not developing new symptoms that are more concerning.

- This patient had gone to an urgent care a few days earlier, and now had come to an ED. Many physicians will do a bigger workup than usual if a patient is a bounceback (although this is extremely context-specific and not the standard of care). The doctor did choose to do a bigger workup than urgent care (CXR and EKG), but no lab testing. ED doctors get criticized for ordering troponins and dimers too often, but it may have saved this patient’s life.

- I’m surprised that the EMS crew wasn’t named in this lawsuit as well. Their note and the signed refusal form provide a vigorous defense, but the testimony from multiple witnesses was that there was pressure to refuse care. It’s impossible to say if this really happened or is self-serving testimony. I’m not arguing that the EMS crew really did put pressure on him to refuse, but the fact that this was exertional syncope should raise more concern than the standard vasovagal or orthostatic syncope that EMS responds to numerous times per day. I think the plaintiff’s attorney realized that the case against the EMS crew would be hard to prove with such good documentation, and that the potential financial benefits were slim.

- I’m worried that the jury was overly harsh on the defendants because they attempted to use the COVID law to avoid liability. There is already a massive public backlash against the way the pandemic was handled, and it’s likely that some jury members harbored hypercritical views about this topic. They may have seen this as their chance to hold authority figures accountable. I wonder if it would be a better defense tactic to only use the COVID laws during pre-trial attempts to have the lawsuit thrown out, but if the judge refuses to dismiss it, purposefully do not use it as an argument in front of the jury. This case happened in a very conservative state. Before everyone gets political in the comment section, I will note that the last lawsuit I published that involved the defense unsuccessfully trying to avoid liability due to COVID laws happened in a very liberal state. If these 2 cases are reflective of a larger trend, it does not seem that these COVID laws actually provided much protection and only gave healthcare workers false reassurance.

Part II – A Discussion with the Jury Foreperson

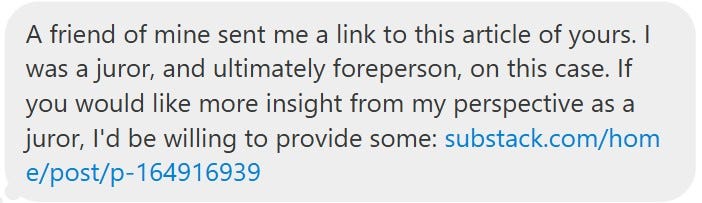

From: The Expert Witness Newsletter

Within a few hours of publishing the Death After ED Visit for COVID case, I received this message in my inbox:

Needless to say, I was really excited to speak with him and get his perspective.

After sending some messages back and forth, it was clear that he knew tons of behind-the-scenes details from the case, in a way that only a jury member would know.

One of the biggest things he pointed out was that the jury did not rule that the ER doctor committed gross negligence.

There was some confusion in the comment section about this.

Because the jury found that the COVID Limited Liability Act did not apply, they used an ordinary negligence standard.

He was kind enough to answer some questions, that were very illuminating.

In the text below, MedMalReviewer questions are in bold, and his answers are in regular text.

MedMalReviewer: Thanks for taking some time to answer these questions! I think it will be really helpful for doctors to hear from a jury member.

I appreciate what you are doing with your blog and I think it’s a good service to the healthcare community. I reached out to you because I believe you sincerely want to report accurate information so that you and your community can draw reasonable conclusions to help in your careers and to serve patients better. I hope that my firsthand knowledge of the trial can help you in this endeavor. Just the fact that you accepted my offer shows a lot of integrity and I appreciate that.

I also understand that you may disagree with some of what I may answer below. It’s possible for two reasonable people to look at the same evidence and draw different conclusions. Once this trial ended, I talked to an ER physician friend of mine and my wife, who is a medical provider, to get their thoughts from the medical professional perspective. I’m the sort of person that likes to understand how things work and to reflect on how I view things. That’s why I’ve stayed so engaged with this case since the trial ended nearly 16 months ago. I even talked with all six attorneys (two for the plaintiff and two each for each defendant) involved in the trial after the trial had ended. I thought they would all like to improve their professional abilities while I also got to get a deeper understanding of the situation from them directly.

For added context, we heard from many medical professional expert witnesses (there were lots of other witnesses too, hospital administration, EMS, family, friends, etc…). The defense brought in a hematologist (which you already talked about on your blog), a pulmonologist, and an ER physician. The plaintiff brought in two ER physicians (but one was actually originally an ER physician expert witness for the defense – they didn’t switch sides, just the defense wasn’t going to use them so the plaintiff made them come anyway since they had a deposition from them).

Finally, I’d like to mention that the patient was a very athletic high school football quarterback before he went to college and stayed very physically active.

I have also attached the jury instructions since it will help answer many of your questions. My answers are in-line with your questions below.

1. Was there any discussion about how an ER doctor is supposed to check for a PE? Specifically in regards to what we call “risk stratification” with Wells, modified Geneva, and PERC score, which are basically just a series of questions you can answer to tell you if there is any risk of PE, without doing blood tests or scans. These things are usually very accurate but it’s clear this patient was a rare exception. A lot of doctors who sent me comments felt that just based on the risk stratification, there was no reason to do any blood tests or scans, but I’m curious how that was presented to the jury.

There was extensive testimony in regards to the PERC score. The doctor testified that he had PERC’d out the patient and they used the doctor’s notes to show that being done indirectly. However, the EKG played a big role to me here. Every expert witness noted the inverted T-waves, but the doctor would not testify to that. He would just testify that “something happening” here, “just kind of goes up,” when asked about it.

Combined with the two week timeline thus far and the waxing and waning of the symptoms, I felt the PERC rule was improperly applied. The pre-test probability (or the gestalt – yes they used that word often at trial) should not have been below 15%. There was also a spot in the lung on the X-ray that expert testimony stated should likely have been noticed by the ER physician, but wasn’t.

2. You mentioned the overreads of the EKG and x-ray were important to the jury. Can you elaborate on how that influenced the jury’s decision?

This was more important to me when it came to the hospital’s negligence. The doctor just noted ST wave changes and nothing on the X-ray. The hospital sent those off for overread which came back with inverted T-waves, consider ischemia on the EKG (just as the computer had reported to the doctor). The X-ray came back with the spot in the lung. The hospital apparently had/has zero process to do anything with those overreads. Literally nothing. I felt the patient should have at least been contacted concerning that X-ray to encourage him to get seen again.

3. Can you clarify what happened when the paramedics came out after he passed out? The records were kind of unclear. It sounds like from your comments that his friends told him not to go? Did they testify to that at trial?

Yeah, he had obviously fainted after running up the stairs. EMS called out. All the vitals checked out fine. The patient knew he had COVID and so was just sort of continuing to power through. From his perspective, he went to urgent care (you have COVID), he went to the ER (you have COVID) and he’s basically just thinking he has to man up and get through this like everyone else he knows that’s had COVID. His friends thought he’d be fine staying home and they testified to that. So I wouldn’t say they told him not to go. This was one of those situations that I picture as the consensus among the patient and his friends that it’d be okay for him not to go. The paramedics wanted to take him, but got their release signed to not take him.

4. Can you tell me what you remember about deciding if the COVID law applied to this case? You mentioned that the jury didn’t necessarily know you were deciding about this at the time, that you were just answering a question. Can you elaborate on that?

In the jury instructions, go to page 38. You’ll see two special interrogatories. These were the first two questions we had to answer. First as it pertains to Dr. L and then as it pertains to the hospital. Ten members of the jury said no as to Dr. L and all twelve said no as to the hospital. As you can see, we were instructed that if we decided no that we would use ordinary negligence. (Editor’s note: the special interrogatory in regards to Dr. L is shown below)

We spent a lot of time discussing these. The defense made the argument that just the fact that he had COVID meant that we should answer yes. I didn’t agree with them on that.

There was lots of testimony (from both sides) that the hospital was properly staffed, they weren’t busy at all at that time (this was Dr. L’s only patient over the course of nearly an hour), all equipment, labs, etc… were available to be used. Our understanding of the interrogatories was that these are the things that would need to be affected to cause us to answer yes. If the hospital is overwhelmed because of too many patients, exhausted staff, not enough resources, experimental treatments, etc… All things that could be caused by the COVID-19 public health emergency. Just the patient merely having Covid didn’t seem to qualify to answer this question yes. Two jurors did think it should be yes for Dr. L, but no juror thought so for the hospital.

5. When the jury decided the doctor would have to pay $4,000,000, how did the jury come up with that number? Did they talk about how much the doctor’s malpractice insurance would pay? Did the jury feel like the doctor would be able to actually pay the $4,000,000 out of his own personal savings?

As you can imagine, placing a dollar value on someone’s life is not easy. We spent a lot of time on this. Jury instruction number 18 told us what we should consider when determining damages: the grief of his parents, the loss of companionship by his parents, and the pain and suffering of the patient. We were not to take into account the ability of anyone to pay the verdict. Ultimately, we were able to get the required nine votes out of the twelve jurors for $10,000,000. We had decided the percentages earlier in our deliberations. So the four million was just the result of that. We also spent a ton of time trying to figure out the percentages of negligence. There were initially 12 different percentages that we had to find agreement on.

6. Was there anything that the ER doctor did or said during the trial that irritated the jury or made him unlikeable? Same question applies to the various experts and the attorneys for each side.

For me, it was a very real problem that he couldn’t admit those were inverted T-waves even at trial. That told me that he felt if he were to admit to such that he was going to lose. If he had said, “yes I identified those as inverted T-waves, but given all the other information and my experience, I thought the PERC rule was appropriate,” it might have changed how I viewed things. I don’t know if it would have changed the verdict, but he felt untrustworthy to me because of this testimony.

The hematologist was very frustrating to me. I felt she talked down to us in a bit of a patronizing way. She also said something that didn’t make logical sense to me. She very specifically said that “PE doesn’t wax and wane” so it was unlikely he had a PE at the ER that day. It was testified by experts on both sides that the body can break down the clots on their own (but heparin would be the fastest resolution), so it logically follows that things can improve then get worse as new clots form, etc… Others also testified it could seem to improve and then get worse for various reasons.

All the other experts were quite trustworthy and I didn’t actually feel like any of them were trying to hide anything or mislead us. ER experts on both sides hurt the defense in this case.

The defense ER expert was Dr. S. I was very impressed with him. He was an excellent witness for the defense. He supported Dr. L’s decision making and consistently said that Dr. L did perform at the standard of care. However, there were a few things that he said that stuck out to me. First, that he would have discussed the EKG findings with the patient. As I mentioned previously, all evidence indicates that these findings weren’t discussed with the patient. During cross-examination it was made clear what he thought about the importance of involving the patient in their care, documenting discussions and rationale for decisions, and communicating considerations for additional testing. All areas that Dr. L seemed to fall short to me. Put another way, part of being a good physician is connecting with your patient and getting them to do what you think they should do. Or, at minimum, being convinced that they fully understand the situation. People skills are just as important as the diagnostic skills.

7. How “close” was the decision? Was everyone on the jury immediately on the plaintiffs side, or did it take a lot of debating back and forth to reach a decision?

I would say that everyone believed that there was no gross negligence on the part of Dr. L. But based on our instructions, definition of negligence, etc… it was pretty clear from the beginning that the plaintiff was going to win. Jury instruction number 29 explains the standard of care to us. We heard from many ER expert witnesses and I was convinced that Dr. L fell below the standard of care.

There were two that felt that the patient was 100% (or at least 50%) responsible because he didn’t go with EMS that day. I think that if we had been asked if the hospital had been grossly negligent, we would have said yes. But for legal reasons that got removed as a question to us.

8. If you had to communicate one big take-home point to ER doctors from this case, what would you say?

I’m going to have to give you two.

First, please don’t think that just telling someone that leaves the ER to follow-up with someone in two days is going to do anything useful (or protect you legally). Patients ignore that because they are told it for everything. You need to find more clear and direct ways to encourage people to seek follow-up if you truly think it’s necessary. For example, in this case, telling the patient that you see something on his EKG (which evidence suggests he was never told about) and you think that needs to be followed-up soon to make sure it’s nothing serious. When that X-ray came back, calling the patient to tell him that there’s something on his X-ray that needs to be looked at. Related, you need to consider how someone is going to receive your words in the complete context of their situation. Essentially, to the patient, he was told twice (by the urgent care and then the ER) to just man up, you have COVID. He learned that there wasn’t anything the doctors were going to do for him so didn’t see a compelling need to go with EMS that day. He already thought he knew what was wrong with him.

Second, I would say that if you end up in trial that you need to be 100% open and honest with the jury. Being an ER doctor is a very hard job and there’s a lot going on. For many, this can be pretty mysterious, but in the end the people on the jury are just people and they should be treated that way. My jury was full of logical thinkers looking to make the right decision. We were able to clearly grasp the concepts presented to us.

9. Do you think Dr L might have won if he had documented some more details about his thinking in regard to PE like “In my opinion, the risk of PE is <15%, therefore he PERC’s out and no d-dimer or CT is necessary” as opposed to him just saying “I see nothing here to suggest pulmonary embolus”.

I honestly can’t say if it would or wouldn’t have changed my final verdict. But it definitely would have been more favorable to Dr. L. I understand that no one likes to do documentation, but when you see dozens of patients in a day, thousands a year, you can’t possibly remember each encounter. In fact, Dr. L clearly testified that he does not remember the patient at all. Which I don’t fault him for. But in that reality, documentation is very, very important. In my view, it’s essential for proper patient care. Much of Dr. L’s testimony boiled down to, “I would have done X because that’s what I always do,” with little evidence to support that claim.

10. Do you think Dr. L might have won if he had documented that he told the patient instructions that were specific to his care like “return if your chest pain gets worse, if your breathing worsens, if you pass out, or if any other new unexpected symptoms arise”?

I think this would have significantly improved his chances of winning and, if true, likely that the patient would still be alive. I viewed the packet of papers of discharge instructions as insufficient since they are often generic and rarely read by patients.

11. In my analysis, I commented that I was worried that some jurors were angry with the healthcare system about how they handled COVID. From your comments it seems that the jurors were rational and logical and wouldn’t have been swayed by simple emotion like this, but I’m curious if there were any comments or sentiment to this effect from anyone on the jury?

I can’t recall one comment from any juror during deliberations being angry or emotional at the healthcare system or its workers for how it handled COVID. We approached this as we were instructed. Applying the facts, which we were the determiner of, to the law.

Personally, I was upset at the hospital for how it deals with overreads (many other jurors had the same sentiment), which appears to be a blatant cash grab with no patient benefit. At least in this setting. I think if that hospital system doesn’t change its ways concerning these that it’s going to end up with a whopper of a punitive verdict from some jury at some point. I think the hospital got lucky here because of some legal minutia.

12. Did any of the plaintiff’s experts try to argue that Dr. L had committed gross negligence? (I see that the jury did not accept this argument, but I’m wondering how hard the plaintiff’s experts argued for it, especially the EM experts)

Obviously, the plaintiffs pushed the gross negligence argument extensively and used the expert witness testimony to provide supporting evidence of that. However, I don’t recall any expert saying gross negligence directly or even implying it. The testimonies were about what was done wrong or how they would have done things differently. Boiling down to many different things that wrap up into a ball that the plaintiffs hoped would be gross negligence in the mind’s of the jury: failure to diagnose PE (via further testing), dismissing of symptoms (just blaming them all on COVID), inadequate action on abnormal findings (i.e. EKG), failure to inform and document, insufficient discharge instructions, reckless use of PERC Rule, lack of follow-up systems (overreads), failure to consider family history (Antithrombin III deficiency).

I’d say that sums up their arguments and the experts were used to support those points. Obviously, those on the jury agreed with some of these things more than others. For example, the ATIII deficiency stuff wasn’t convincing to me. It was essentially an argument about a note from the mom not being delivered to the doctor.

This made me think of something else you haven’t asked about yet. Was the link between COVID and PE discussed? The answer to this question would be yes, extensively. There were even documents that the hospital had produced for their staff making it pretty clear that it was well-established at the time that COVID was a known risk factor for PE.

MedMalReviewer Analysis:

- One thing that surprised me most about this conversation was how important the cardiologist’s EKG overread and final radiology report were to the jury. ER doctors don’t generally pay much attention to the computer report (it’s catastrophically inaccurate and overcalls ischemia constantly) or the cardiology overread (which comes through hours later and is done primarily for billing). It seems the jury thought that the lack of follow-up protocols for these findings demonstrated negligence on the part of the hospital, but less so on the part of the ER doctor. It’s hard for me to think that this single case will cause hospitals to change their protocols, but it’s also hard to ignore the fact that letting ED doctors bill for their own EKGs (as opposed to cardiology) might reduce the hospital’s liability. The hospital was making $8.51 per EKG doing this (Medicare rate), but ended up losing $3,500,000 (plus legal expenses). They’re going to have to bill over 400,000 EKGs to make up for that.

- Something I re-learned from this case was the difference between contributory negligence and comparative negligence. Many decades ago, most states had pure contributory negligence meaning that if a patient was found to be even 1% responsible, the plaintiff could not recover anything. Almost all states have now switched to comparative negligence, whereby each defendant is responsible for their percentage of liability, even if the patient was also found to be negligent. The state in which this case occurred has a bit of a hybrid model called the modified comparative or 51% bar rule. If the patient is determined to have 51% or higher contributory negligence, the plaintiff doesn’t recover anything. Since the patient in this case was found to be 25% responsible, both the doctor and hospital are responsible for their assigned share of the damages.

- A couple of notes about documentation:

- The doctor explicitly mentioned “pulmonary embolus” in his MDM. It was done in the context of a differential of things that he had ruled out based on history and exam. I’ve heard lots of conflicting advise about whether or not it’s good to document a differential for legal defensibility. One of the most common questions I get is “should I document a differential?” I lean slightly more towards documenting a limited differential, but I don’t always do it and I’m slowly realizing there’s not great evidence to support either side of this argument.

- The jury member thinks that documenting more detailed support of his differential might have cast Dr. L in a more favorable light, but it probably would not have changed the verdict. In some ways this feedback suggests that documenting a complicated differential doesn’t really help, because Dr. L likely still would have lost. But on the other hand, it would have cast him in a more favorable light, and even a slight improvement in how the jury views you could become extremely valuable in a close case.

- The only thing that the jury member said could have “significantly” increased his chance of his winning was to discuss and document specific return precautions. The automatic/template advice about return precautions on the discharge papers held basically no weight for this jury. Likewise, generic advice about follow-up held little weight. Instead, telling the patient the specific reasons he needed to follow-up and why it was important seemed to be key. This case suggests that if you are going to choose between documenting a differential and discussing/documenting aftercare (return precautions and follow-up plan), you’re better off focusing on the aftercare. I’m not sure if this advice generalizes to other cases, but it’s worth keeping in mind when deciding where to focus your limited time.

- I spent some time reading through the jury instructions in detail, and thought it was really useful. In particular, instruction 19 had some great definitions of “negligence” and “ordinary care”. These are terms we toss around a lot and their meaning can become a bit nebulous, so it’s good to see how they’re being defined for the jury right before they decide on a case.

- When I first published this case, I had mistakenly thought that EMS may have pressured him into refusing. It turns out that wasn’t the case at all. It was the patient who refused, apparently with some input from his friends. Now that I look back and re-read the EMS documentation in this light, I’m very impressed by it. Their documentation was rock solid and may have prevented them from getting sued. Excellent work by our pre-hospital colleagues.

- I feel some sense of relief that the plaintiff’s expert witnesses did not try to argue that this was gross negligence. I think there were some valid criticisms, but I felt that if they had tried to argue gross negligence it would have been extremely unethical and grounds for public censure.

- One of the ways this case challenges the standard practice of EM is that it points out the downsides of Wells and Geneva. We all know that technically these risk stratification tools can deliver false results a tiny percentage of the time, but it’s so rare that the standard practice of EM is to proceed as if it’s ironclad. We don’t have a robust mental model for “overruling” low risk (<15% PE probability) Wells or Geneva that are also PERC negative. If they’re low risk, they’re low risk, other factors be damned. That approach works the vast vast vast majority of the time, but it didn’t here.

- The standard teaching is that PERC only applies if risk stratification with Wells or Geneva indicated a probability of PE less than 15%. However, I think we’re pretty bad at assigning a percentage of likelihood once we start assessing risk factors outside of those that are explicitly defined by Wells and Geneva. Take for example a patient who has a Wells score of one (1.3% chance of PE), but you also note they just had a cross country road trip and that both of their parents died of unprovoked PEs at a young age. You instinctively know that their risk is elevated, but how much? Does that increase their risk by 5, 10, 25%, or more? Once we start incorporating factors outside of those already accounted for by Wells and Geneva, we really don’t have much concrete data and are making guesses about their risk. The doctor in this case was expected to go beyond Wells and Geneva, and realize that the history and EKG raised the likelihood of PE above 15%. I’m not sure there’s any data that would support assigning a specific percentage for this patient, whether its higher or lower than 15%. Many doctors have had the experience of thinking they had a slam dunk PE case, and yet were proven wrong in the end. We’re actually not very good at guessing which patients are going to have a PE. If you think you’re good at knowing which patients have PEs, it’s because you don’t actually see high volumes of undifferentiated patients. It’s called the great imitator for a reason!

- I was vaguely familiar with the idea that COVID increased the risk of venous thromboembolic disease (VTE), but I did not realize how significant this association was. In the early days of the pandemic, the likelihood of an otherwise healthy outpatient getting a VTE within 30 days of COVID was 0.1-0.2% (absolute risk extrapolated from this paper). For comparison, the odds of a woman on estrogen-containing OCPs developing a VTE within the first 30 days is 0.01-0.03% (source). I choose that comparison because doctors are accustomed to seriously considering the risk of VTE in women on OCPs. It’s drilled into our heads in med school and residency, and it’s even part of PERC. And yet, the odds of VTE in COVID patients during this time period were up to 10x higher than that. The odds of VTE in COVID patients last year (2024) were still elevated, although have come down a lot due to vaccination and repeat infection, estimated at 0.05-0.1%. Still notably higher than women on OCPs. You could make an argument from this data that you need to add a few percentage points of risk (but no one knows how much exactly) to whatever Wells/Geneva is calculating, and that you should never use PERC on a COVID patient. I’m not sure I entirely buy this argument and I definitely don’t think it defines the standard of care, but it’s a good thought exercise.

- One theme I’ve noticed in writing malpractice cases is that it can be really hard to make a diagnosis when there are 2 simultaneous diseases. Even the best doctors in the world, practicing far above the standard of care, can miss these. In this case, it was COVID and pulmonary embolism. Here are some others we’ve covered:

EMCrit Takes…

T-Wave Inversions as a Sign of PE

Are present in right heart strain

Kosuge et al. [10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.10.043] showed, in a case control study between known PE and known ACS patients, Anter0-inferior TWIs (particularly III and V1) were common in PE and incredibly rare in ACS

Witting et al. [10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.07.026] did another case control between PE, ACS, and non-cardiac chest pain patients. A 1-mm T-wave inversion was seen in both III and V1 in 11/97 (0.113) of patients with PE vs. 9/194 (0.046) controls. But really the only finding that had reasonable LR+ was

2-mm T-wave inversions in III, aVF, V1,& V2: Sensitivity (4%), Specificity (100%), LR+ 16, LR- 1.0

Vereckei et al. [10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.05.042 ] derived a novel ECG score which has not been validated, I am not advocating you use it, rather, look at it and see the complexity it would require to get good test characteristics from the ECGs.

Oklahoma Gross Negligence Standard

In Oklahoma, negligence rises to the level of gross negligence when the conduct demonstrates a conscious disregard for the safety of others, exceeding a simple lack of due care. It’s not just carelessness, but rather a willful and reckless disregard for the well-being of others, showing a conscious indifference to potential harm, according to legal resources

Open Evidence’s Take on the ?

Reddit Thread on This Case

Additional New Information

More on EMCrit

You Need an EMCrit Membership to see this content. Login here if you already have one.