August 08, 2025

4 min read

Key takeaways:

- About 50% of enrollees with high eRADAR scores had MCI or dementia.

- Only 30% of participants completed their visits.

- The researchers recognized the need for outreach to underrepresented communities.

An electronic screening tool shows promise for detecting cognitive impairment and dementia risk in older adults, but outreach is needed to boost participation to assess its feasibility in a primary care setting, per to a presentation.

The electronic health record Risk of Alzheimer’s and Dementia Assessment Rule (eRADAR)” “is an [electronic health record]-based risk score to identify people who are at high risk of having undiagnosed dementia,” Deborah E. Barnes, PhD, MPH, epidemiologist in the Weill Institute for Neurosciences at the University of California, San Francisco, said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Data were derived from Barnes DE, et al. Evaluating targeted dementia screening of high-risk patients in primary care: Preliminary results from the electronic health record Risk of Alzheimer’s and Dementia Assessment Rule (eRADAR) pragmatic randomized trial. Presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference; July 27-31, 2025; Toronto.

An ongoing clinical trial, whose main purpose is to establish whether eRADAR’s implementation in a primary-care setting will increase the rate of dementia diagnosis, is being conducted at UCSF and at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute.

Eligible participants were aged 65 years and older and did not have a dementia diagnosis or dementia medications. Researchers used eRADAR to screen EHRs for patients who were “high risk” based on approximately 30 variables.

“Demographic variables include things like age and sex. It includes some chronic health conditions and diagnoses like diabetes and heart failure. It includes some vital signs like underweight and some medications,” Barnes said.

Health care utilization variables such as primary care and ED visits are among the variables as well, she continued.

Patients with eRADAR scores in the highest 15% to 20%, indicating greatest risk, were contacted first via mail and followed by phone calls. At the primary-care level, patients were randomized to receive an invitation for a “brain health” assessment via in-person visit, video or phone or receive usual care.

The primary outcome for the study is the rate of dementia diagnosis after 12 months, with secondary outcomes related to qualitative assessments of the study on those involved.

A baseline brain health visit was conducted either by phone or video conference and led by a licensed clinician. Patients were encouraged to have a care partner along for the assessment.

Deborah E. Barnes

Issues related to memory or thinking, along with analysis of daily living activities, potential depression symptoms and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), were examined. At UCSF, the intervention was offered in English, Spanish, Cantonese and Mandarin, with English only at Kaiser.

Following the session, a patient summary and recommendations for treatment were provided, with a clinical note passed onto the primary care provider. Those with suspected dementia were encouraged to follow up with their PCP within a month, after which the PCP would order testing to make a diagnosis.

Interventionists then monitored patient charts for 4 months. In case of a lack of follow-up, researchers called patients as a reminder, and if no new diagnosis was made, additional resources were offered.

A post-visit survey additionally assessed the patient’s acceptance of the treatment and satisfaction with the intervention.

At UCSF, 1,271 individuals were split on a 1:1 basis between the intervention arm (n = 683) and standard care arm (n = 588), while among the 3,417 participants at Kaiser, 1,715 were given the intervention and 1,702 placed in standard care.

According to results, at UCSF, 637 individuals received study outreach, 222 (35%) agreed to a visit and 197 (31%) completed the visits. At Kaiser, the figures were 1,706 who received outreach, 554 (32%) who agreed to a visit and 505 (29%) who completed visits.

“They didn’t answer their phone. Maybe they weren’t reading their mail,” Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD, senior investigator, physician and affiliate associate professor at Kaiser, said during the presentation. “Some just weren’t interested.”

Patients who completed visits had a mean age of 83.4 years at KPWA and 83.6 years at UCSF; were 57% female at KPWA and 52% female at UCSF; and 88% white at KPWA and 61% white at UCSF.

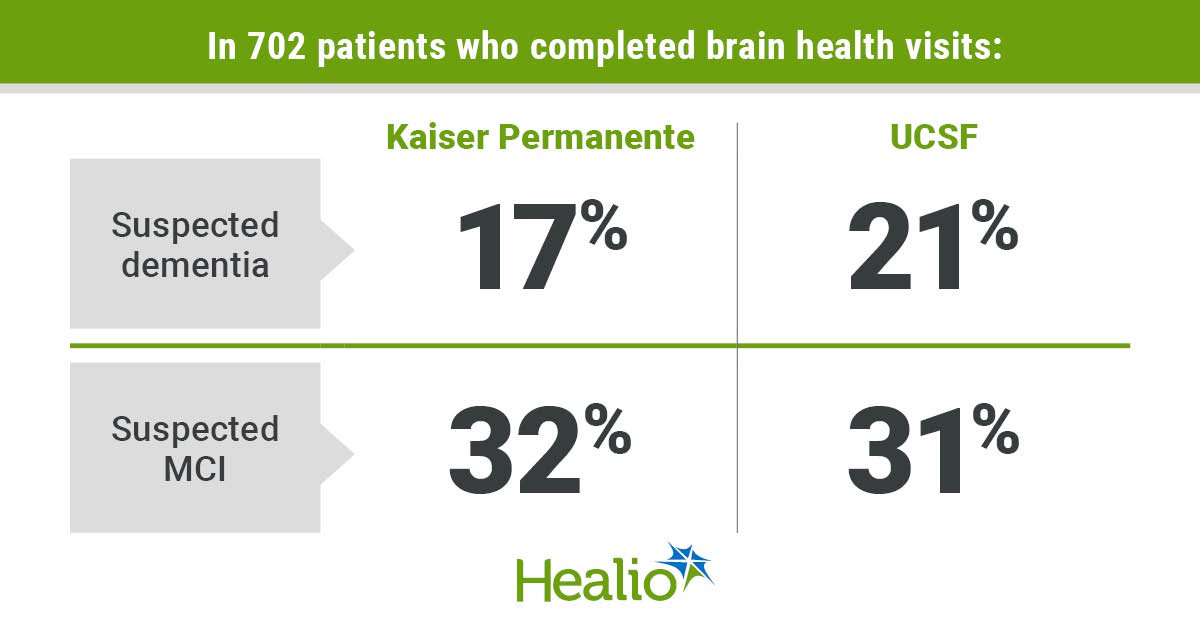

Regarding the outcomes of the brain health visits, 21% of the 197 at UCSF and 17% of the 505 at Kaiser were suspected dementia cases, while 31% at the former location and 32% at the latter showed evidence of mild cognitive impairment.

Among those who completed the study visits at UCSF, 50% did so by video and 57% had a care partner present; at Kaiser, 74% were conducted in person and 72% had a care partner included.

In the patient satisfaction survey, participants were asked if they found the visit helpful, if they found the interventionist put them at ease and if they felt comfortable talking about brain health. For UCSF enrollees, agreement was approximately 90% to 96% for all three questions and at Kaiser it was roughly 91% to 98%.

“This is a population who now is able to get enhanced care. They might have easier access to new disease-modifying therapies,” said Dublin,. “We think eRADAR shows a lot of promise for maybe identifying people who could get early intervention, maybe a behavioral intervention.”

Such interventions would emphasize physical activity or new pharmacologic treatments, Dublin continued.

Among the reasons researchers found for lack of participation were time and logistic challenges, cultural stigma, and more pressing health concerns and conditions in an aging population, particularly in those aged 90 years and older.

Data further showed that at UCSF, a significantly higher proportion of non-Hispanic white English-speaking participants completed their visit compared with English-speaking Asian, Black and Hispanic participants. In addition, a higher percentage of non-English-speaking Asian participants completed their visits vs. Hispanic participants.

At Kaiser, non-Hispanic white enrollees had the highest completion rates, with lower rates found in Hispanic, Black and Asian patients.

“It’s really important that we keep pursuing research and develop new strategies to support participation among communities of color and people whose preferred language is not English,” Dublin added.

For more information:

Deborah E. Barnes, PhD, MPH, can be reached at: psychiatry@healio.com.

Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD, can be reached at psychiatry@healio.com.