December 03, 2025

1 min watch

Key takeaways:

- Cognitive errors like confirmation bias can lead to diagnostic inaccuracy in rheumatology.

- Misdiagnosis of complex conditions is common in rheumatology.

CHICAGO — Cognitive errors, which can sometimes stem from “data overload,” can lead to misdiagnoses of complex rheumatic and autoimmune diseases, according to two presentations at ACR Convergence 2025.

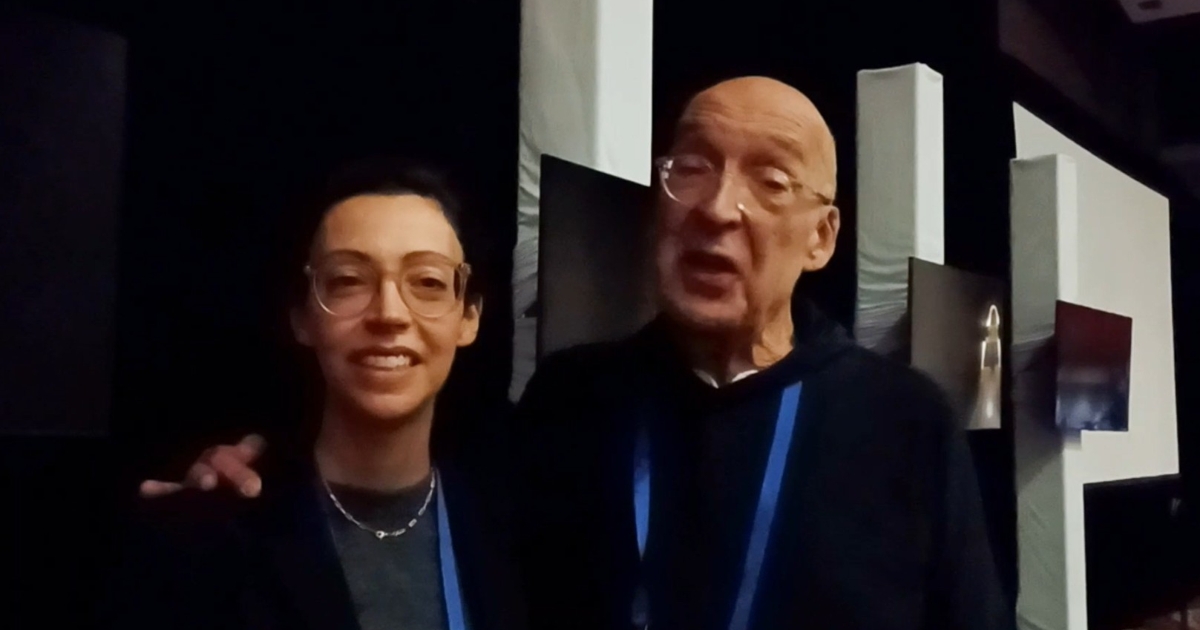

“Why should rheumatologists be concerned about diagnostic error of non-rheumatic diseases? This is a question that everyone has a visceral feeling about,” said Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, professor of medicine at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, RJ Fasenmyer chair of clinical immunology at the Cleveland Clinic, and chief medical editor of Healio Rheumatology. “It can have cataclysmic consequences.”

“Cognitive errors in clinical reason potentially leading to diagnostic inaccuracies are our greatest threat,” said Cassandra Calabrese, DO.

There are multiple reasons why diagnostic uncertainty is so common among rheumatic and autoimmune diseases, according to Calabrese. Although physicians in other specialties can work from guidelines, recommendations and diagnostic criteria that apply to all or most patients, rheumatologists do not have that luxury, he said.

“We have many classification criteria that we have created through the school of hard knocks,” Calabrese said. “Many patients do not meet these criteria.”

Another issue is that many conditions under the rheumatology umbrella are multi-systemic.

“No one is an expert in all systems,” Calabrese said.

These gaps in knowledge about specific organ and bodily symptoms can lead to misdiagnoses, according to Calabrese. Conversely, for rheumatologists who attempt to grasp all of the systems involved in a particular patient’s presentation, “data overload” can cause diagnostic uncertainty, he said.

All of these factors can lead to cognitive error, which Calabrese said may be the biggest issue for many rheumatologists who misdiagnose a patient.

“It is analytical and systematic,” he said, describing the heuristics of diagnoses. “It is not enough just to have the facts. The facts have to agree with our own reasoning.”

Rheumatologists are often forced to create a hypothesis based on the data from the various systems impacted in any given patient, and then use pattern recognition to determine which diagnosis is most appropriate. However, if the data have been gathered ineffectively — an incorrect blood test or a misreading of ultrasound or imaging results, for example — the entire diagnostic process can be thrown off.

“It must include meta-cognitive awareness and reflection,” Calabrese said.

Ultimately, he said, rheumatologists should have one skill when making a diagnosis: “tolerance of uncertainty.”

In the next presentation of the same session, Cassandra Calabrese, DO, assistant professor in the departments of rheumatic and immunologic disease and infectious disease at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, expanded on these ideas surrounding diagnostic uncertainty.

“Cognitive errors can lead to premature closure,” she said, adding that “confirmation bias” can lead rheumatologists to make an incorrect diagnosis based on the flawed data. “Avoid premature closure.”

Rheumatologists should be aware of two critical “heuristics, or mental shortcuts” often used in diagnosing complex conditions, she said. One is Occam’s razor, which states that the simplest explanation is probably correct.

Conversely, Hickam’s dictum is often more appropriate in the rheumatology setting, according to Cassandra Calabrese.

“A patient can have as many diseases as he damn well pleases,” she said, repeating the dictum.

However, even when a rheumatologist remembers both rules, the result is not always a correct diagnosis.

“These heuristics can go well or they can go poorly,” she said.

Meanwhile, so-called “anchoring bias” is another potential pitfall rheumatologists should avoid when making diagnoses, according to Cassandra Calabrese.

She described a patient with symptomatology consistent with polymyalgia rheumatica, and so she assumed that was the case, since those conditions often go together.

“My colleague handed me this diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica, but it was not polymyalgia rheumatica,” she said. “Taking time to gather data is critical.”

Ultimately, both Leonard and Cassandra Calabrese delivered the same message for rheumatologists to consider as they take what they learned at ACR back to their practices.

“Cognitive errors in clinical reason potentially leading to diagnostic inaccuracies are our greatest threat,” Cassandra Calabrese said.

For more information:

Cassandra Calabrese, DO, can be reached at calabrc@ccf.org.

Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, can be reached at calabrl@ccf.org.