I’m writing a letter to the editor in response to a recent article in the Journal of Hospital Medicine. I’m posting it here rather than submitting it to the journal to avoid burying it behind a paywall (and because I have the attention span of an intensivist hopped up on lots of coffee).

First, I would like to congratulate the authors on writing a thought-provoking article that does a good job of pointing out the very scant evidentiary basis behind the issue of torsade due to ondansetron.

A critical point was discussed in the article and bears repetition here. Ondansetron causes the greatest prolongation of QT when provided as a rapid intravenous push, causing serum levels to spike transiently. Strategies to mitigate this might include administering a slow infusion over 10 minutes or an oral disintegrating tablet (ODT).

The authors state in the article that “The medical literature includes only two documented cases of TdP associated with ondansetron administration: one patient had a history of cardiomyopathy and received 36 mg of intravenous ondansetron over 24h, and the second patient presented with severe hypokalemia after 12mg of intravenous ondansetron.” I don’t believe that this is accurate. A cursory literature review discloses at least five cases. (31428390, 37085406, 29259513, 35012656) Some of these involved using low doses of ondansetron (4 mg). While I agree with the authors that reported cases of ondansetron-induced torsades are rare, there are more than two reported cases and torsades may potentially occur at commonly utilized doses.

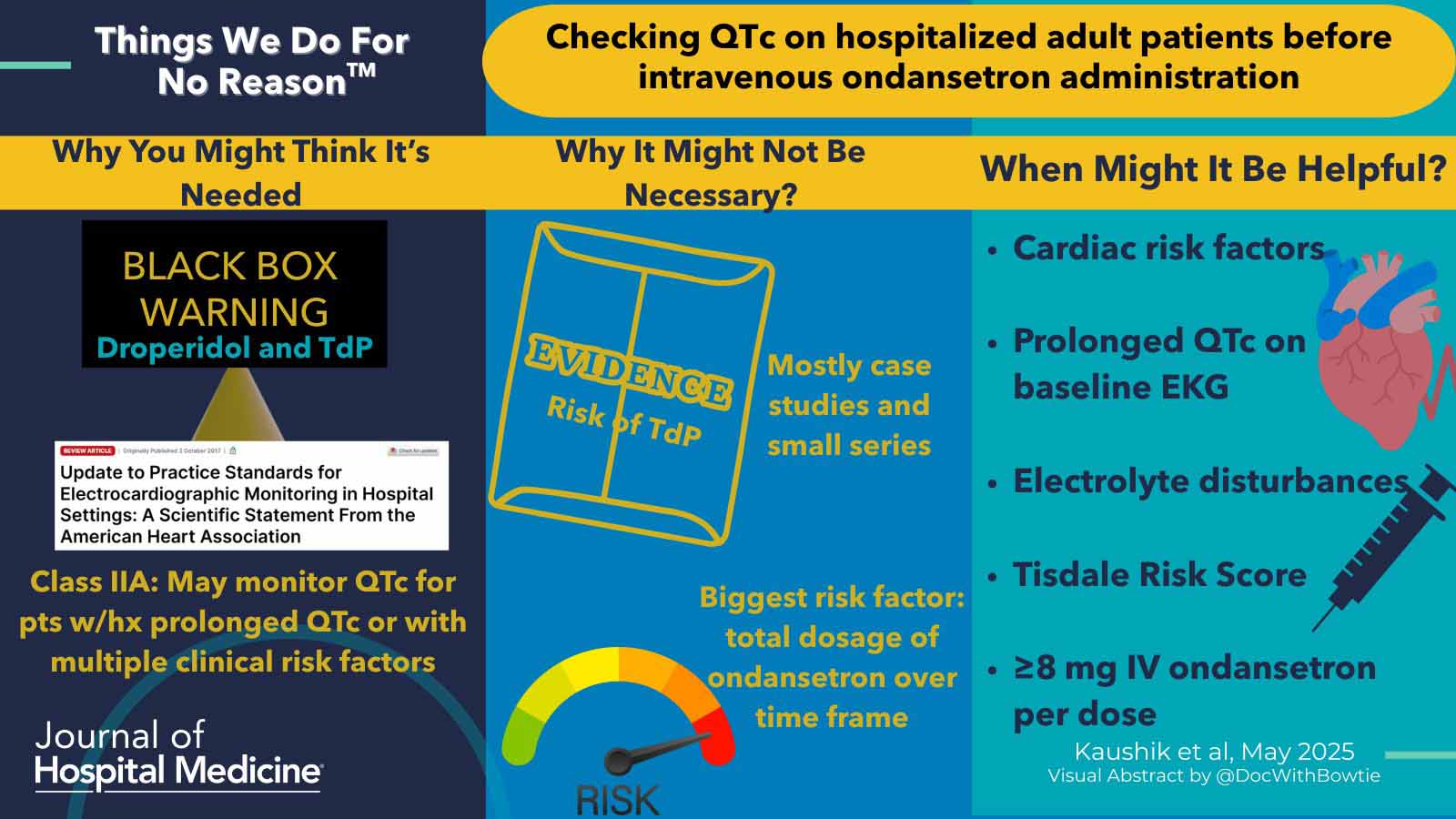

The authors seem to propose using a Tidsdale risk score for QT prolongation to obviate the need for an initial ECG prior to the administration of ondansetron. Specifically, the article states: “Hospitalists need not order an initial and subsequent ECGs when administering standard doses of intravenous ondansetron for patients without significant risk factors for QTc prolongation. To assess risk factors and stratify risk of QTc prolongation, hospitalists should apply the Tisdale score to guide clinical management for adult patients.” However, the Tisdale score requires an admission QTc measurement (figure below). Since the Tisdale score is based on an admission QTc measurement, it cannot be used to obviate the need for an initial ECG (the Tisdale score may be used to avoid the need for serial repeat ECGs during the patient’s hospital stay).

Ultimately, where does this leave us in terms of utilizing ondansetron safely and sensibly? Given the very sparse evidentiary basis, making any strong recommendations is impossible. However, here are some parting thoughts that I have on the topic:

- I would argue that any adult sick enough to be admitted to the hospital should get an admission ECG. This is useful for evaluating for myocardial ischemia (which can itself cause nausea/vomiting!) and as a baseline tracing. By the time a hospitalist or intensivist has been called to admit the patient, there should already be an initial ECG in the chart.

- The Tisdale Risk Score seems like a reasonable tool for minimizing the need for serial repeat ECGs during a patient’s hospitalization.

- For any patients on telemetry, electronic calipers can be used to calculate the QTc interval (example below). This technology is increasingly incorporated into the electronic medical record in a fashion that may allow it to be performed immediately and at zero cost. For patients on telemetry, measuring the QTc with electronic calipers is faster and more accurate than computing a Tisdale Risk score.

- Torsade de pointes due to ondansetron is incredibly rare. Therefore, any thoughtful approach to this is probably fine – in fact, it’s probably way above the average standard of care. The problem occurs when folks aren’t considering this at all.

- Sublingual ondansetron is probably safer than IV ondansetron because it achieves a lower peak serum level. Available RCTs suggest that 8 mg sublingual ondansetron has similar efficacy compared to 4 mg IV ondansetron (although these studies have real limitations). Sublingual ondansetron has a slower onset, which may make it less desirable for severe nausea. However, sublingual ondansetron may be a good option for mild nausea, since it is probably safer and cheaper than IV ondansetron.