October 06, 2025

3 min read

Key takeaways:

- More than half of people using semaglutide or tirzepatide reported reductions in appetite and food cravings.

- Adults who reported more intense sweet or salty tastes were more likely to have increased satiety.

Adults with obesity who reported more intense tastes while receiving semaglutide or tirzepatide had a higher likelihood for increased satiety and decreased appetite and food cravings, according to a presenter.

In a cross-sectional study presented at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes annual meeting and published in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, researchers surveyed adults with obesity who were using semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy, Novo Nordisk) or tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Eli Lilly) and asked about changes in their appetite, satiety and sensory perception after starting an incretin-based therapy. Researchers found some adults reported increased intensity of sweet and salty tastes, and increased intensity of both types of tastes were tied with greater odds for increased satiety. However, change in taste did not affect weight-related outcomes.

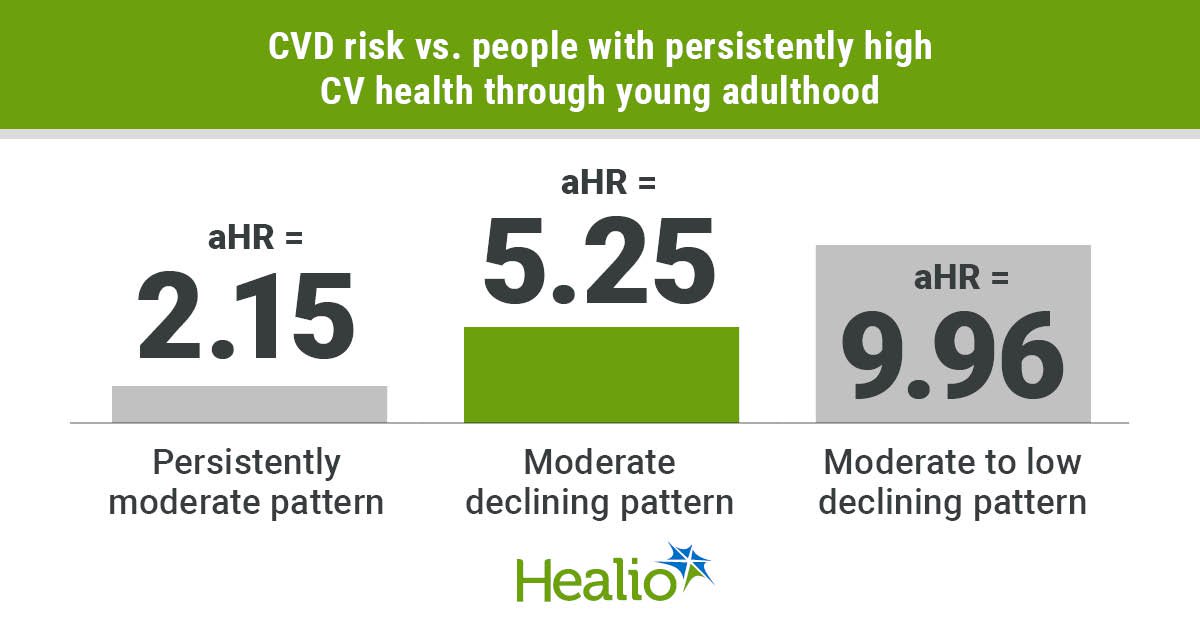

Infographic content were derived from Moser O. Abstract 803. Presented at: European Association for the Study of Diabetes Annual Meeting; Sept. 15-19, 2025; Vienna.

“This means that taste perception changes may serve as markers of appetite response rather than predictors of treatment success,” Othmar Moser, PhD, professor in the division of endocrinology and diabetology in the department of internal medicine at Medical University of Graz in Austria and in the division of exercise physiology and metabolism at the Institute for Sports Science at University of Bayreuth in Germany, told Healio. “The findings highlight the nuanced ways incretin therapies act beyond pure metabolic regulation.”

Othmar Moser

Researchers conducted a survey of 411 adults aged at least 18 years with obesity or overweight with at least one weight-related comorbidity who were receiving semaglutide or tirzepatide (median age, 39 years; 71.8% women). Demographics, lifestyle factors, self-reported medical history and anthropometric measures, and therapy information were collected. Participants provided answers to questions on eating behavior, appetite, satiety and sensory perception with Likert responses.

Of the participants, 217 were receiving Wegovy, 148 were receiving Ozempic and 46 were receiving Mounjaro.

Obesity drugs alter eating behaviors

More than half of participants said they had either a slight or large reduction in appetite with obesity therapy, including 54.4% of the Wegovy group, 62.1% of the Ozempic group and 56.5% of the Mounjaro group. Slight or strong reductions in food craving were reported by 66.8% of Wegovy users, 64.2% of those using Ozempic and 63% of the Mounjaro group. Increased satiety was reported by 66.8% of adults using Wegovy, 58.8% of the Ozempic group and 63.1% of adults using Mounjaro.

A greater sweet taste intensity was reported by 19.4% of the Wegovy group, 21.6% of the Ozempic group and 21.7% of the Mounjaro group. Salty taste increased in intensity for 26.7% of participants receiving Wegovy, 16.2% of those using Ozempic and 15.2% of the Mounjaro group. There were no significant differences for any of the appetite, satiety or taste questions between the three medications.

“GLP-1 and GIP receptors are present in taste buds, the brainstem and higher brain regions that process taste and reward,” Moser said of the mechanisms behind the taste changes. “Activating these pathways may heighten taste intensity and alter how food cues are valued, dampening hedonic drive. The therapies may also modulate gut-brain signaling, changing how sweetness and saltiness are encoded during digestion. Together, these mechanisms create a recalibration of taste and appetite regulation. Thus, incretin therapy influences not just metabolism but also sensory and reward pathways.”

Taste changes tied to satiety, appetite

In multivariable analysis, adults who reported increased intensity for sweet taste had higher odds of increased satiety (adjusted OR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.14-4.57), decreased appetite (aOR = 1.67; 95% CI, 1.04-3.25) and reduced food cravings (aOR = 1.85; 95% CI, 1.06-3.29). Increased intensity in salty taste was tied to a higher likelihood for increased satiety (aOR = 2.17; 95% CI, 1.16-5.17).

Self-reported changes in taste were not tied to changes in BMI.

Moser said more research is needed that utilizes objective taste and smell testing in addition to patient-reported outcomes, as well as assesses taste both before and after initiation of obesity treatment.

“Neuroimaging and molecular work could reveal how incretins act on central and peripheral chemosensory pathways,” Moser added. “It will also be critical to link these sensory shifts to real-world eating patterns and long-term outcomes.”

Moser said researchers could also try to identify which patients experience the greatest benefits related to taste in hopes of personalizing therapy in the future.

For more information:

Othmar Moser, PhD, can be reached at othmar.moser@uni-graz.at or on LinkedIn @OthmarMoser.