September 08, 2025

4 min read

Key takeaways:

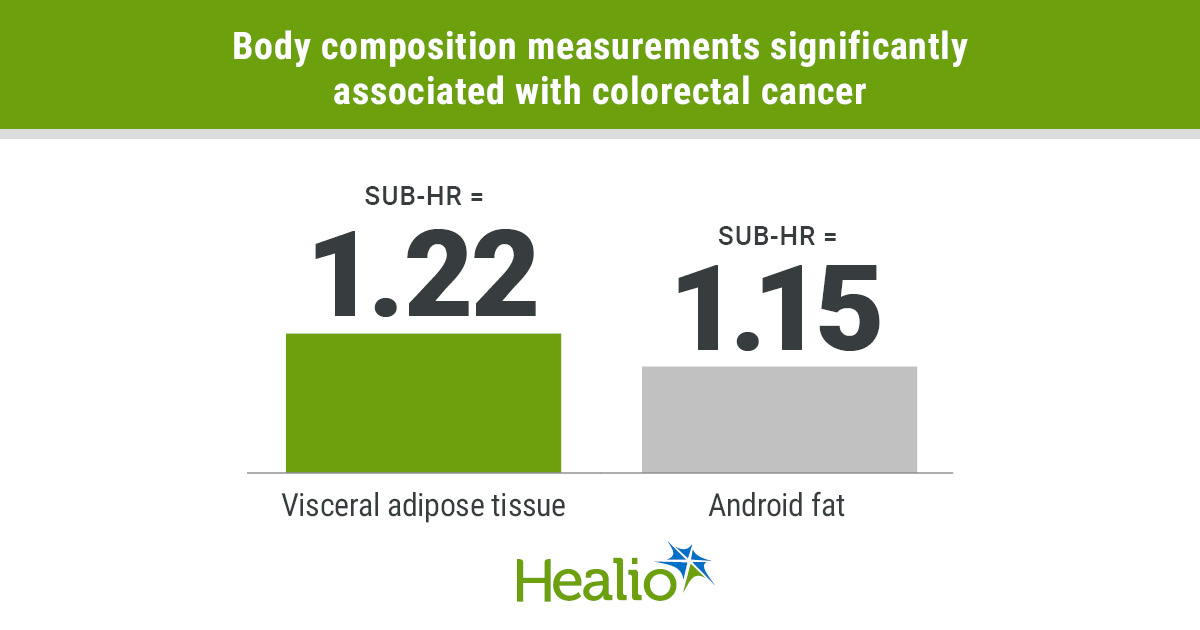

- Visceral adipose tissue and android fat had significant associations with risk for colorectal cancer.

- Body composition could be a better way to determine risk compared with BMI.

Body composition measurements may be better predictors of colorectal cancer incidence than BMI.

An evaluation of more than 9,000 postmenopausal women who had dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry-determined adiposity found those with higher visceral adipose tissue and android fat had greater risk for developing the malignancy. Those with increased subcutaneous adipose tissue, more closely related to BMI, did not.

Data derived from Ziller SG, et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2025;doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-25-0581.

Shelby G. Ziller

“Numerous studies have examined the relationship between anthropometrically defined obesity and colorectal cancer incidence, leading to its classification as an obesity-related cancer,” Shelby G. Ziller, MPH, biostatistician and PhD student in epidemiology at University of Arizona College of Public Health, told Healio. “However, this study offers a unique contribution to the understanding of body composition in adiposity and colorectal cancer in women.

“These distinctions may be crucial, as certain depots of fat are metabolically active and can contribute to inflammation, which is a hallmark of colorectal cancer. Our work emphasizes the importance of moving beyond proxy variables like BMI to incorporate measured and more accurate tissue-level variables in our understanding of colorectal cancer risk.”

‘We rely heavily on BMI’

Colorectal cancer incidence continues to rise in the U.S. The American Cancer Society, in its Cancer Statistics 2025 report, estimated there would be 154,270 new cases and 52,900 deaths from the malignancy, making it the fourth most common cancer with the third highest mortality.

Multiple studies over the past 20 years have linked colorectal cancer with obesity, and approximately 40% of people in the U.S. can be classified as obese based on BMI, according to study background.

However, BMI may not be the best measurement for certain populations.

Ziller and colleagues noted previous research that found patients with higher BMI had lower mortality than those with “normal” weight.

“In research, we heavily rely on BMI,” Ziller said. “It’s fine for getting a general idea of what’s going on in the public, but for more accurate and individualized care, it’s not good.”

The researchers hypothesized that certain fats may have a stronger relationship with colorectal cancer. They investigated this among postmenopausal women who underwent dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

Commonly used for diagnosing osteoporosis, DXA can now be used to measure subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue.

“These women who are postmenopausal are losing bone mass and starting to lose muscle mass as they get older, but they may stay same weight,” Ziller said. “You’ll get people who look normal weight but are not actually healthy.”

The Women’s Health Initiative enrolled more than 160,000 postmenopausal women into various clinical trials and observational studies between 1993 and 1998. A subset of those were enrolled in a DXA cohort. They received serial scans for 6 years.

Ziller and colleagues evaluated 9,950 participants (mean age, 63.3 years; standard deviation, 7.4; mean BMI, 28.2 kg/m²; standard deviation, 5.7) in the DXA cohort.

The association of DXA-measured adiposity and colorectal cancer incidence served as the primary endpoint. The link with colorectal cancer mortality served as the secondary endpoint.

‘Pretty big deal’

In all, 191 women developed first-incident colorectal cancer (mean age, 74.3 years; standard deviation, 8.5) and 88 women died of the disease after 27 years of follow up.

Among the fats measured, visceral adipose tissue (per 100 cm²) had a significant association with colorectal cancer incidence (sub-HR = 1.22; 95% CI, 1.01-1.48), as did android fat (sub-HR = 1.15; 95% CI, 1.01-1.31).

“Visceral adipose tissue is seen as a bad actor,” Ziller said. “It is related to several known causes of cancer, like chronic inflammation, metabolic disruption and immune disfunction. Seeing this area we know has problems is also associated with disease risk is a pretty big deal.”

Visceral adipose tissue is the fat that surrounds organs, particularly the abdomen, and android fat is found from the bottom of the last rib to the top of pelvis, Ziller said.

Conversely, subcutaneous adipose tissue did not have a significant association with colorectal cancer incidence.

Ziller and colleagues did not observe an association between any measured fats and colorectal cancer mortality.

They did acknowledge study limitations, including the small number of cases and deaths among the cohort.

‘More to the world than BMI’

A key step in future research involves a head-to-head comparison between high levels of visceral adipose tissue and BMI to determine which is the best predictor of colorectal cancer incidence.

Additionally, men and younger women also should be investigated, Ziller said.

These data could help identify which individuals are at greater risk.

“[Scans could be] part of screening possibilities when people are 45 and older, when they’re getting their colonoscopies,” Ziller said. “They should probably be getting their body composition measures assessed, as well.”

CT scans and MRI could be used to measure these fats, too, and are more common than DXA. However, they have drawbacks.

“A DXA scan is a lot less expensive than a CT, even out of pocket, and the radiation is considerably lower as well, which is why we think it is a good alternative,” Ziller said. “If you take an adiposity measurement from an MRI vs. DXA, there is actually a high correlation between them. It’s not a gold standard, but we think it is a good option if your concerns are going to be based on cost and radiation.”

Change likely will not happen, though, until insurance companies start accepting measures other than BMI.

“We have to show insurance companies that there is more to the world than BMI,” Ziller said. “Until insurance companies start moving on this, I don’t know how we’re going to continue. The only way we’re going to move the insurance companies is if more studies take measurements besides BMI.”

For more information:

Shelby G. Ziller, MPH, can be reached at sziller@arizona.edu.