August 01, 2025

3 min read

Key takeaways:

- Education level plus residence in the U.S. vs. Puerto Rico as a Puerto Rican individual impacts asthma mortality.

- Researchers observed findings that refute the Hispanic Mortality Paradox.

Age-specific and -standardized asthma mortality rates were greater among Puerto Rican individuals with lower education attainment living in the U.S. vs. in Puerto Rico, according to study data.

These results were published in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

Data were derived from Nazario S, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2025;doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2025.03.027.

“The findings of this study provide a comprehensive understanding of how education influences asthma mortality rates among different racial and ethnic groups, including [Puerto Ricans],” Sylvette Nazario, MD, allergy & immunology program director at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus, and colleagues wrote.

Using 2011 to 2020 data from the National Center for Health Statistics, Nazario and colleagues evaluated Puerto Rican individuals split up based on if they lived in Puerto Rico or the U.S. to determine how asthma mortality differs between these individuals and how education impacts asthma mortality.

In addition to both sets of Puerto Rican individuals, this study collected mortality rates of Hispanic individuals in the U.S. minus Puerto Rican individuals, non-Hispanic Black individuals and non-Hispanic white individuals.

In terms of crude asthma mortality rates, researchers found a higher rate in Puerto Rico vs. the U.S. (24.32 per 100,000 vs. 10.97 per 100,000) in the assessed timeframe.

Switching to age-specific and -standardized asthma mortality rates, the greatest rate out of the five groups was 28.76 per 100,000 among non-Hispanic Black individuals, according to the study. Puerto Rican individuals living in the U.S. had the second highest rate at 25.42 per 100,000, and Puerto Rican individuals living in Puerto Rico had the third highest rate at 23.85 per 100,000. The remaining two groups had rates below 10 per 100,000.

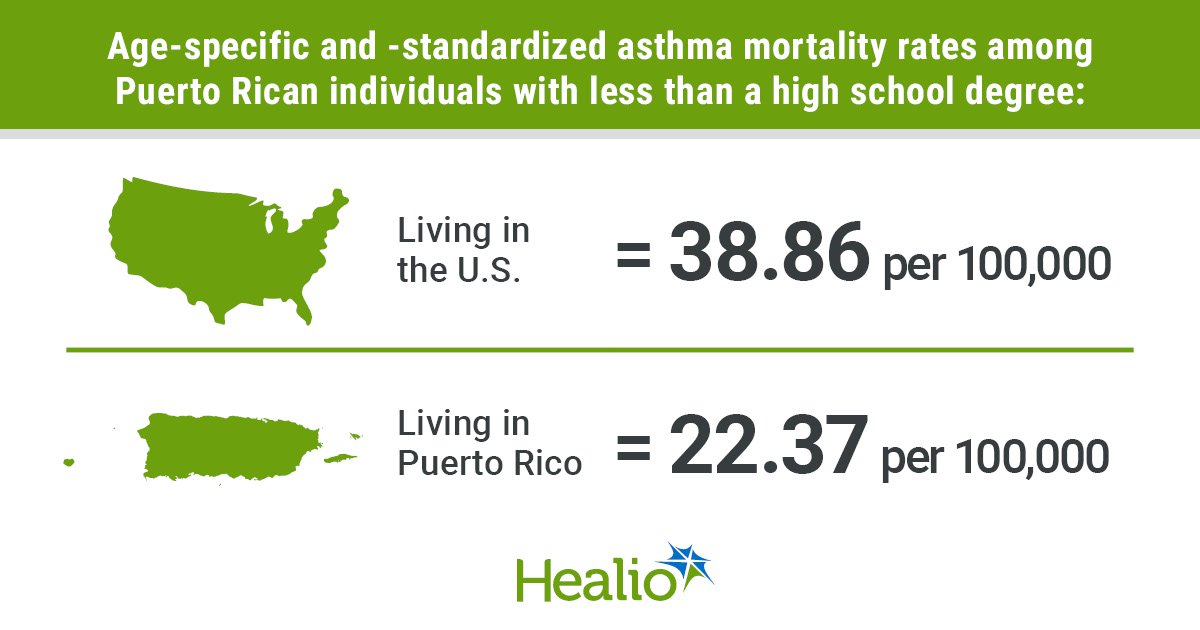

Researchers went on to adjust for education and observed significantly greater age-specific and -standardized asthma mortality rates among Puerto Rican individuals living in the U.S. vs. in Puerto Rico with less than a high school degree (38.86 per 100,000 vs. 22.37 per 100,000) and only a high school degree (46.3 per 100,000 vs. 15.45 per 100,000).

This outcome was also true when comparing Puerto Rican individuals living in the U.S. vs. non-Hispanic white individuals with less than a high school degree (38.86 per 100,000 vs. 12.58 per 100,000) and only a high school degree (46.3 per 100,000 vs. 12.55 per 100,000). With greater mortality rates observed among Puerto Rican individuals living in the U.S. vs. non-Hispanic white individuals, researchers contradicted the Hispanic Mortality Paradox, which suggests that mortality rates are smaller among Hispanic immigrants vs. non-Hispanic white individuals “despite facing lower socioeconomic conditions and worse environmental exposures.”

In each population, as educational attainment went up, most asthma age-specific and -standardized rates (ASRs) went down, according to the study. However, not all changes from one attainment level to another reached significance.

For example, in Puerto Rican individuals living in Puerto Rico, the change in ASR from less than a high school degree to a high school degree was significant (22.37 per 100,000 to 15.45 per 100,000), whereas the changes in ASR from less than a high school degree to a bachelor’s degree (12.47 per 100,000) and to a postgraduate degree (12.29 per 100,000) were not significant.

Notably, researchers highlighted that the change in ASR from less than a high school degree to a postgraduate degree in Puerto Rican individuals living in the U.S. was significant (38.86 per 100,000 to 8.39 per 100,000; 78.4% reduction), as was the change from less than a high school degree to a bachelor’s degree (38.86 per 100,000 to 18.65 per 100,000; 52% reduction).

“Education contributes to reducing ASR but impacts inconsistently [Puerto Rican] populations, suggesting that other factors are at play,” Nazario and colleagues wrote.

According to the study, wage improvement with education was slower among Puerto Rican individuals living in Puerto Rico than other populations.

Researchers also found several other characteristics that differed between Puerto Rican individuals living in Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican individuals living in the U.S., with all but one (home ownership) demonstrating unfavorable/less helpful outcomes among those living in Puerto Rico:

- median income ($18,660 vs. $36,558);

- proportion at poverty level (41.7% vs. 24.2%);

- proportion that speak English at home (4.8% vs. 35.9%);

- proportion above 65 years (15.2% vs. 6.6%);

- proportion with public insurance (57.7% vs. 41.5%); and

- proportion that owned a home (69.8% vs. 38.1%).

Building on the idea that more than education influences asthma mortality, the study reported that non-Hispanic white individuals with less than a high school degree had a similar ASR (12.58 per 100,000) to three populations with a postgraduate degree: non-Hispanic Black individuals (12.9 per 100,000), Puerto Ricans individuals living in the U.S. (8.39 per 100,000) and Puerto Rican individuals living in Puerto Rico (12.29 per 100,000).

“Increasing educational attainment is an equity goal,” Nazario and colleagues wrote.