August 04, 2025

3 min read

Key takeaways:

- More frequent HCV testing was cost-effective among people who inject drugs in both high- and low-transmission settings.

- Harm-reduction strategies, such as syringe services, also improved cost-effectiveness.

Testing for hepatitis C virus infection every 6 to 12 months — or even more frequently — among people who inject drugs could be a beneficial, cost-effective strategy, according to a study published in JAMA Health Forum.

Lin Zhu

“Offering HCV testing to people who inject drugs at least once a year may be a good option, and fostering engagement in HCV care among people who inject drugs by creating a non-stigmatizing and supportive health care environment would be helpful,” Lin Zhu, PhD, assistant professor in the department of public health sciences at University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, told Healio. “When feasible, implementing evidence-based strategies to reduce risk of reinfection among patients who inject drugs would enhance the health and economic benefits of HCV testing and treatment.”

Data derived from Zhu L, et al. JAMA Health Forum. 2025;doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2025.1870.

Transmission of HCV among people who inject drugs (PWID) is mostly through sharing of needles, syringes and other injection equipment, according to researchers.

Although the impact and cost-effectiveness of HCV treatment, testing and care has been widely studied, little is known about optimal testing frequency in this population.

“Chronic hepatitis C is a leading cause of liver cancer in the United States,” Zhu, who previously served as senior research engineer in the department of health policy at Stanford University, said. “The advent of highly efficacious and well-tolerated direct-acting antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virus has raised prospects for HCV elimination. However, progress toward this goal has been limited, especially among PWID, who account for the majority of both prevalent and incident cases.”

Zhu and colleagues used a dynamic, agent-based network simulation model of HCV transmission through shared injection equipment to determine the benefits and cost-effectiveness of various testing frequencies among PWID.

Their analyses included testing in a PWID setting with lower HCV transmission as well as a higher transmission one. They used data collected from November 2008 to August 2010, complemented by published results from the literature for the network simulation.

Changes in cumulative quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), health care costs over 60 years (in 2021 U.S. dollars) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), discounted at 3% annually, served as primary outcomes.

The simulated population included 1,552 PWID (median initial age, 32 years).

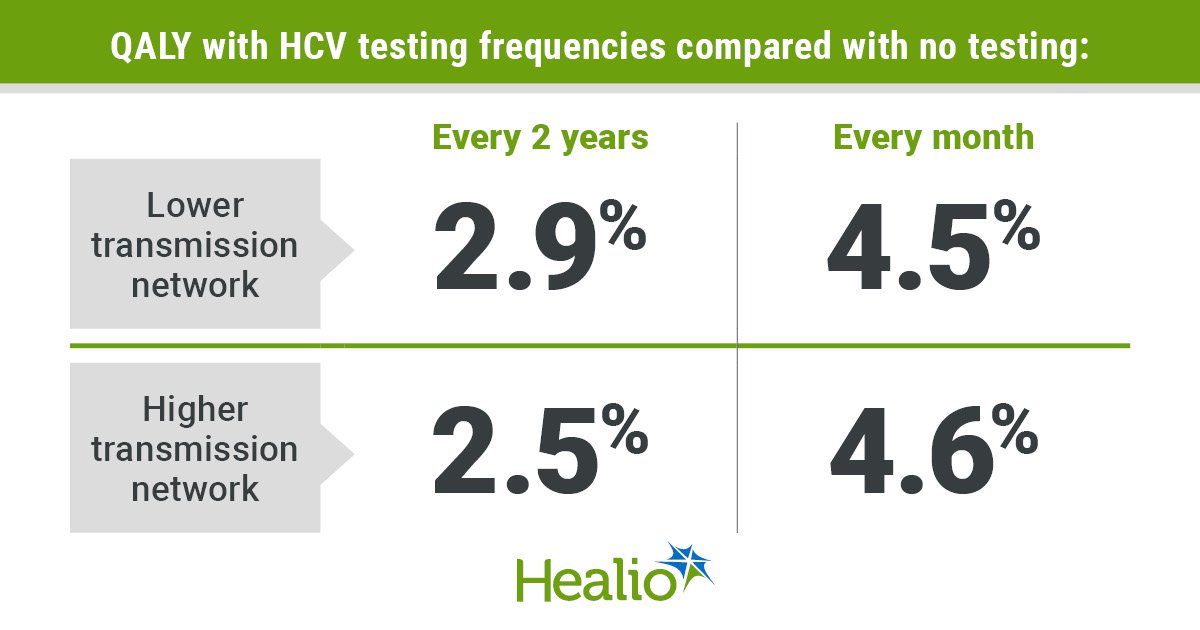

Results showed that increasing HCV testing frequency to between every 2 years and every month increased QALYS by 2.9% to 4.5% in the lower transmission network and by 2.5% to 4.6% in the higher transmission network, compared with no testing. Costs also increased by 0.5% and 2.3% when increasing the frequency of testing from every 2 years or once monthly compared to no testing.

In the lower transmission setting, ICERs were $6,000 per QALY for testing every year, $9,300 per QALY every 6 months, $24,200 per QALY every 3 months and $138,400 per QALY every month; testing every 2 years was weakly dominated by more frequent testing strategies.

In a higher transmission setting, ICERs were $14,000 per QALY for testing every 6 months, $30,100 per QALY every 3 months and $93,300 per QALY every month; testing every 2 years and testing every year were both weakly dominated.

“HCV testing among PWID every 6 or 12 months had incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of less than $15,000 per quality-adjusted life year gained compared with no testing, assuming a status quo continuum of care and no additional harm-reduction services,” Zhu said. “These ICERs would be regarded as indicating very high value for money compared with commonly used benchmarks suggesting that ICERs less than $100,000 to $150,000 per QALY are considered reasonable.

“In addition, increasing access to and utilization of HCV care among PWID and incorporating harm-reduction services, such as syringe services and medications for opioid use disorder, would further improve the cost-effectiveness of HCV testing and treatment,” she added.

The researchers acknowledged study limitations, including that monthly health care cost estimates for PWID were derived from a clinical trial setting and might be high for community-dwelling PWID, who may have lower health care access.

“This likely overestimated the total health care costs in all scenarios but disproportionately affected the scenarios with high frequencies of testing, since HCV testing and treatment would increase the average lifespan of PWID,” Zhu told Healio. “If monthly health care costs associated with drug use are lower, frequent HCV testing and treatment can be more attractive.

“Future studies providing such costs could help to improve cost-effectiveness analysis results,” she added.

For more information:

Lin Zhu, PhD, can be reached at l.zhu3@med.miami.edu.