Authors: Derick Sanchez, MD (EM Resident Physician, ACMC – Oak Lawn, IL); Michael Cirone, MD (Associate Program Director, ACMC – Oak Lawn; Clinical Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, University of Illinois – Chicago) (@mcironeMD) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Yale University, CT); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 62-year-old male with a past medical history of osteoarthritis presents to the ED with bilateral lower extremity weakness. He states that for the last few months, he has had an increasingly difficult time climbing stairs. He notes progressively worsening neck pain and stiffness for the past year. This morning, his wife urged him to come in because she noticed he was having trouble holding a cup of coffee in his hand.

Vital Signs

HR: 83

BP: 114/68

RR: 16

O2: 98% on room air

Temp: 37C

General: Appears mildly uncomfortable. Sitting upright in a cart

HEENT: Pupils equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation, extra-ocular movements intact.

Cardiac: Regular rate and rhythm

Pulmonary: Clear to auscultation bilaterally

Abdominal: Soft, non-distended, non-tender

MSK: Midline neck tenderness at the level of C5 without step-offs, visible discomfort with range of motion of the neck

Neuro: Cranial Nerve (CN) 2-12 intact, weakness with bilateral hand grip, 5/5 strength bilateral upper extremity flexion and extension, 4/5 strength in hips bilaterally, 5/5 strength with knee and ankle flexion and extension. Sensation intact to light touch throughout. Bilateral knee hyperreflexia. Upgoing Babinski.

Labs unremarkable, including ESR and CRP.

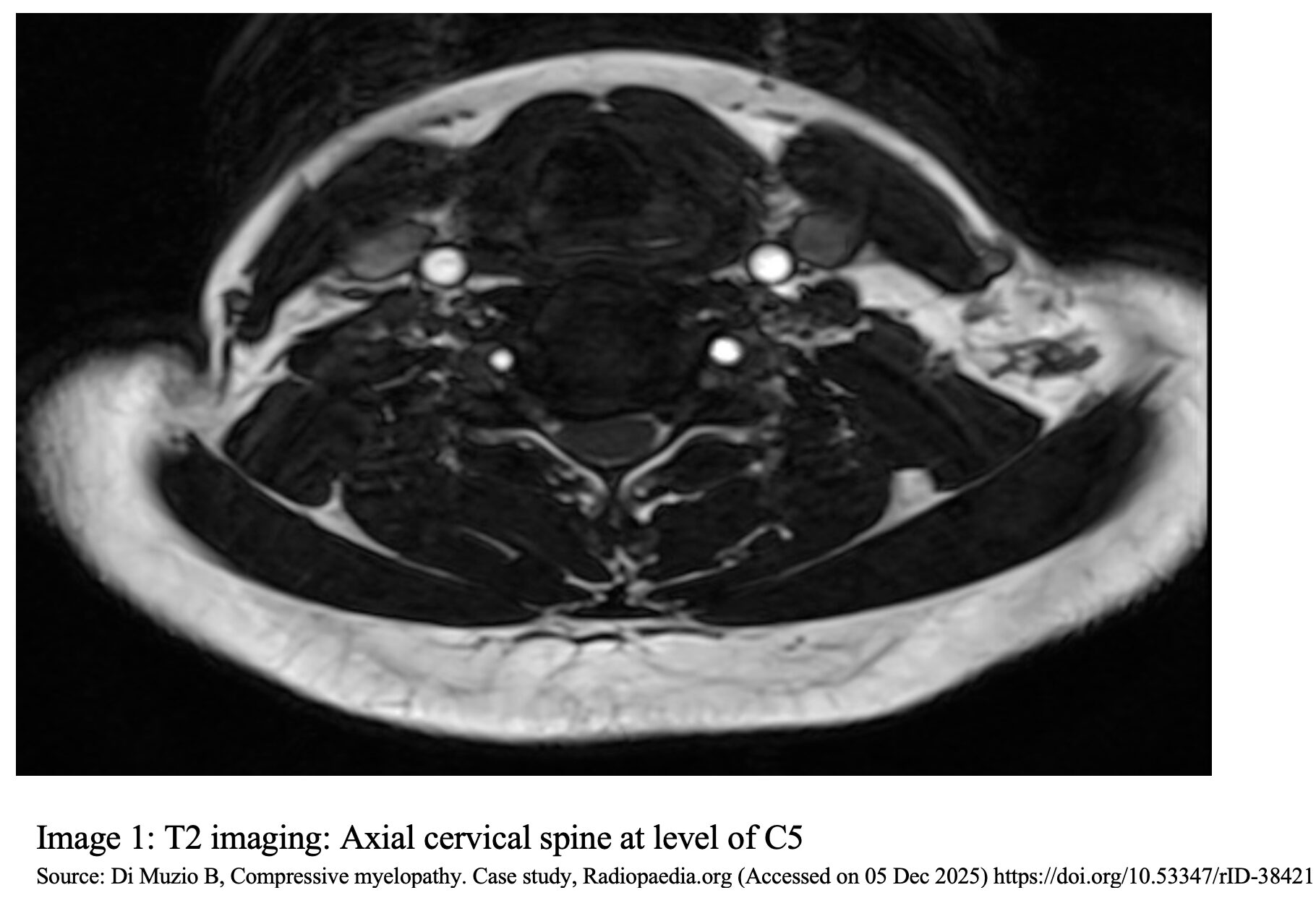

MRI Cervical spine: T2 imaging at the level of C5 with a hypo-intense signal surrounding the cord and flattening of the central cord, giving a kidney bean appearance (image 1)

Question: What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Cervical Myelopathy

Background

- Cervical myelopathy is defined as compression of the spinal cord in the cervical spine, causing neurologic symptoms.1-3

- Most commonly caused by degenerative disease or spondylolysis.

- Can also be caused by trauma or congenital abnormalities.3

- When caused by degenerative disease, it is a progressive condition with symptoms that can range from mild neck pain to more severe neurologic deficits.

Etiology

- When degenerative, the process of chronic and progressive compression of the spinal cord leads to inflammation, ischemia, and clinical findings consistent with cervical myelopathy.1,3,4

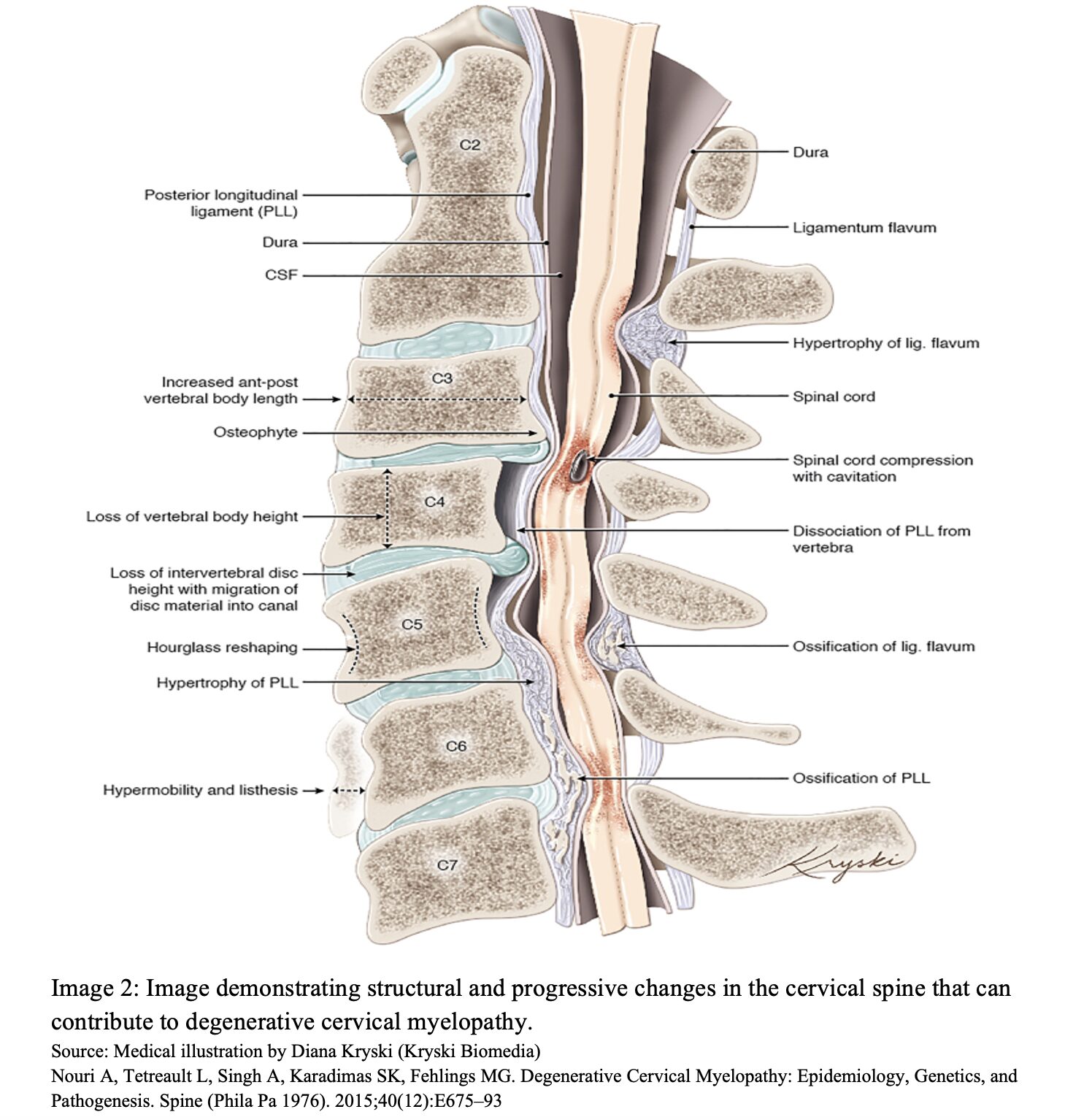

- Cervical spine pathology that can cause cervical myelopathy (image 2): 2,5

- Hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament

- Hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum

- Ossification of the ligamentum flavum

- Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament

- Osteophytes of the cervical vertebra

- Cervical disk herniation

- Ligamentous hypertrophy is caused by fibrosis, which accumulates over years of repetitive mechanical stress.6

- Symptoms usually occur in the lower extremities due to the peripheral location of the lower extremity nerve fibers.2,7

- Congenital anomalies include a narrow spinal canal, a wide spinal cord, or a combination of the two (cord-canal mismatch).8

- Traumatic injury can cause a fracture or misalignment of the cervical spine that can cause cord compression.

- Trauma can also cause acute worsening of existing disease, leading to an abrupt onset of more severe symptoms.

Epidemiology

- Degenerative cervical myelopathy is the most common form of non-traumatic progressive spinal cord compression and need for cervical spine surgery worldwide.1,8

- The majority of patients present in their late 50s to early 60s.2,9

- More common in men compared to women, with a distribution of 3:1.2

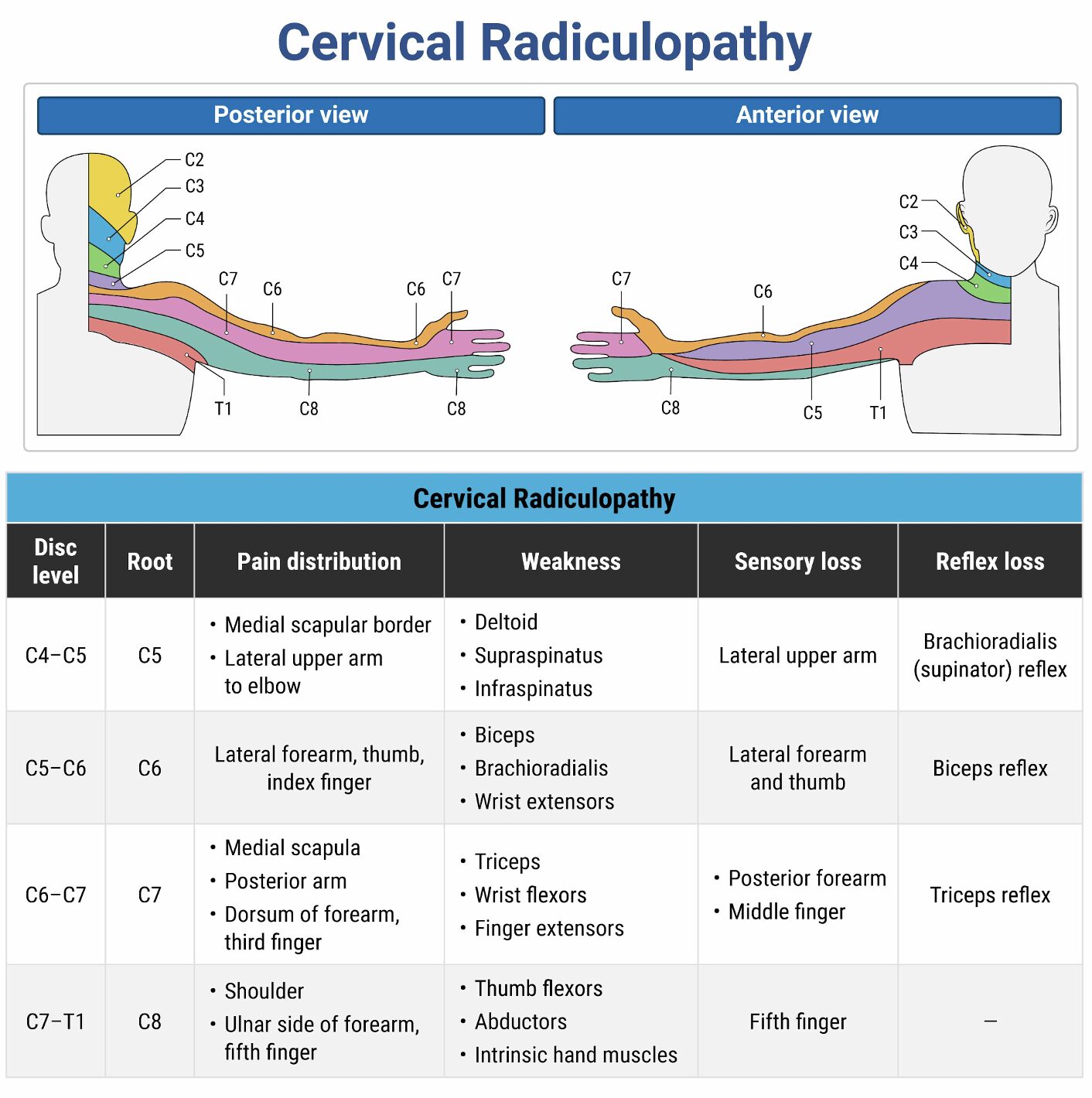

- C5-C6 is the most common site (35.1%) of cervical cord compression, followed by the two surrounding segments (C4-C5 and C6-C7).10,11

Evaluation

- Mild symptoms may include neck pain or stiffness.

- Pain with radiation in the upper extremities or shoulders.

- More advanced symptoms may include gait instability, ascending paresthesia, or weakness in the proximal lower extremities.12

- Bowel or bladder dysfunction can occur in more severe disease.

- Hand weakness and loss of dexterity are hallmark symptoms of cervical spinal cord compression.2,12

- Due to compression and injury of the spinal cord, upper motor neuron lesions are usually present.

- Disease in the upper cervical spine usually causes more generalized symptoms in the upper and lower extremities, such as gait and balance issues, and upper motor neuron signs. Further down the cervical spine, symptoms become more specific to the spinal level of disease, typically causing numbness, weakness, or hyperreflexia.12

- 79% of patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy will have at least one of the below clinical signs. That increases to 95% of patients with MRI spinal cord signal abnormalities.13

- Clinical Signs present in moderate to severe disease:2,8

- Hoffman sign

- Opposition of the thumb and flexion of the index finger with flicking of the middle finger.

- Inverted brachioradialis reflex

- Flexion of the wrist and digits with tapping of the styloid process of the radius.

- Lhermitte’s phenomenon

- Shooting electrical sensation down the spine with flexion of the neck.

- Hyperreflexia

- Proprioceptive loss

- Decreased hand dexterity or hand weakness

- Clonus

- Babinski Sign

- Upward fanning of the toes with upward stroke of the bottom of the foot.

- This along with sustained clonus is a late finding.

- Hoffman sign

Imaging

- MRI with and without contrast is the gold standard for assessing compression of the spinal cord (image 3).1,10

- MRI with neck in a neutral position has a sensitivity of 81.4% and specificity 88.3%. Increased sensitivity and specificity when MRI done with neck in extension.14,15

- Lack of full circumferential hyper-intensity on T2-weighted surrounding the cord can suggest some degree of stenosis from disruption of spinal fluid.10

- Deformity of the spinal cord can appear as a “kidney bean” with flattening of one side.

- Hypo-intense signaling within the cord on T1-weighted imaging suggests a greater degree of cord injury, advanced disease, and a poorer prognosis.1

- CT imaging of the cervical spine can give a detailed view of misalignments or bony abnormalities but is not sensitive for spinal cord involvement.10

- Patients with contraindications to MRIs may undergo a CT myelography with spinal contrast; however, it is not preferred or commonly done due to invasiveness and risk.1

- Plain radiographs in AP and lateral views can evaluate for gross bony characteristics such as disc height, cervical spine alignment, and osteophytes, but are not diagnostic for myelopathy.

- Often, young or asymptomatic patients can exhibit imaging suggestive of cervical degeneration on X-ray and CT; thus, clinical correlation is important.10

Disposition

- Consult spinal surgery (neurosurgery or orthopedics).

- Findings that usually prompt emergent imaging and admission:

- Severe or rapidly worsening neurological deficits

- Onset of symptoms following recent trauma

- Urinary or bowel retention or incontinence

- Gait disturbances or loss of balance

- Frequent falls with concern for safety to return home16

- Many patients with mild symptoms do not need imaging in the emergency department and can be discharged with outpatient imaging and spine specialist (neurosurgery or orthopedic surgery) referral.

Treatment

- For mild to moderate symptoms, treatment can be conservative and determined outpatient; however, many patients experience little improvement and progress to requiring surgical management at some point.1

- Non-surgical options:

- Physical therapy and exercise therapy

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories

- Cervical traction

- Orthotic immobilization

- 20-60% of patients treated non-operatively with mild to moderate symptoms will progress to more severe disease within 3-6 months.17

- Surgical consideration is strongly recommended in patients with moderate (and, at times, mild disease) given the likelihood of progression.17

- Patients should be counseled on recognition of progression of symptoms and avoidance of hazardous activities, such as activities or occupations requiring repeated neck movement or that put the patient at risk for physical injury, that could lead to acute progression of myelopathy.18

- Definitive management usually consists of surgery to stabilize, decompress, or fuse the cervical spine.

Pearls

- MRI is the gold standard imaging modality, but CT can identify contributory or suggestive findings.

- A focused physical exam looking for upper motor neuron lesions can assist in making a diagnosis.

- Early neurosurgical or orthopedic consult or follow-up should be encouraged, as patients treated more aggressively earlier have better outcomes.

Which one of the following physical examination findings suggests cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy rather than a musculoskeletal cause for a patient’s neck pain?

Which one of the following physical examination findings suggests cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy rather than a musculoskeletal cause for a patient’s neck pain?

A) Focal point tenderness near the cervical spine

B) Increased pain with shoulder abduction

C) Neck pain alone in response to the Spurling test

D) Shock-like paresthesias upon flexion of the neck

Correct answer: D

Shock-like paresthesias upon flexion of the neck (known as the Lhermitte sign) suggest cervical myelopathy, indicating spinal cord involvement. This symptom is a hallmark of central nervous system pathology and helps differentiate neurologic causes from musculoskeletal neck pain.

Neck pain is a frequent presenting symptom in the ED and a leading cause of chronic musculoskeletal disability in the United States. The etiologies are diverse, ranging from benign musculoskeletal strain to life-threatening spinal or infectious pathology.

The differential diagnosis of neck pain includes a wide array of conditions: traumatic injury, degenerative spine disease, muscular strain, facet joint arthritis, discitis, meningitis, spinal epidural abscess, spinal tumors, herniated intervertebral discs, epidural hematoma, and transverse myelitis. Among neurologic causes, cervical radiculopathy involves compression or irritation of the nerve root, whereas cervical myelopathy refers to dysfunction of the spinal cord itself. This distinction is clinically critical, as spinal cord lesions typically require urgent or emergent evaluation and intervention to prevent permanent neurologic deficits.

While many cases of neck pain are due to benign soft tissue strain or degenerative changes, certain red flags should prompt immediate consideration of more serious pathology. These include Lhermitte phenomenon, unilateral or bilateral hand weakness, gait instability, new bowel or bladder symptoms, fever, unexplained weight loss, known immunosuppression, history of malignancy, or intravenous drug use. The presence of these features necessitates prompt laboratory workup and advanced imaging.

While plain radiographs of the cervical spine may identify gross bony abnormalities or alignment issues in trauma, they are typically of limited use in nontraumatic presentations of cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. MRI is the preferred modality for evaluating the spinal cord, intervertebral discs, and soft tissues, and it is critical for identifying compressive lesions, inflammation, infection, or neoplasms. When infection is suspected, additional evaluation with complete blood count, inflammatory markers, and blood cultures may be warranted.

Focal point tenderness near the cervical spine (A) is more indicative of a localized musculoskeletal issue, such as a strain or facet joint irritation, not neurologic disease.

Increased pain with shoulder abduction (B) reflects musculoskeletal or rotator cuff pathology rather than cervical nerve root or spinal cord involvement.

Neck pain alone in response to the Spurling test (C) is nonspecific. A positive Spurling sign suggests radiculopathy only when it reproduces radiating arm symptoms, not just localized neck discomfort.

Further Reading

References

- Williams J, D’Amore P, Redlich N, Darlow M, Suwak P, Sarkovich S, Bhandutia AK. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Evaluation and Management. Orthop Clin North Am. 2022 Oct;53(4):509-521. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2022.05.007. Epub 2022 Sep 14. PMID: 36208893.

- Kane SF, Abadie KV, Willson A. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(12):740-750.

- Zhang AS, Myers C, McDonald CL, Alsoof D, Anderson G, Daniels AH. Cervical Myelopathy: Diagnosis, Contemporary Treatment, and Outcomes. Am J Med. 2022;135(4):435-443. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.11.007

- Theodore N. Degenerative Cervical Spondylosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):159-168. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2003558

- Nouri A, Tetreault L, Singh A, Karadimas SK, Fehlings MG. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Epidemiology, Genetics, and Pathogenesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(12):E675–93

- Sonam Vadera, Yuranga Weerakkody. Ligamentum flavum hypertrophy. Radiopaediaorg. Published online January 8, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-65416

- Fotakopoulos G, Georgakopoulou VE, Lempesis IG, et al. Pathophysiology of cervical myelopathy (Review). Biomed Rep. 2023;19(5):84. Published 2023 Sep 25. doi:10.3892/br.2023.1666

- Gibson J, Nouri A, Krueger B, et al. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: A Clinical Review. Yale J Biol Med. 2018;91(1):43-48. Published 2018 Mar 28.

- Milligan J, Ryan K, Fehlings M, Bauman C. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: Diagnosis and management in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65(9):619-624.

- Lannon M, Kachur E. Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Clinical Presentation, Assessment, and Natural History. J Clin Med. 2021;10(16):3626. Published 2021 Aug 17. doi:10.3390/jcm10163626

- Matsumoto M, Fujimura Y, Suzuki N, et al. MRI of cervical intervertebral discs in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):19-24. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.80b1.7929

- Theodore N. Degenerative Cervical Spondylosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):159-168. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2003558

- Rhee JM, Heflin JA, Hamasaki T, Freedman B. Prevalence of physical signs in cervical myelopathy: a prospective, controlled study. Spine. 2009;34(9):890-895. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819c944b

- Al-Ryalat NT, Saleh SA, Mahafza WS, Samara OA, Ryalat AT, Al-Hadidy AM. Myelopathy associated with age-related cervical disc herniation: a retrospective review of magnetic resonance images. Ann Saudi Med. 2017;37(2):130-137. doi:10.5144/0256-4947.2017.130

- Park WT, Min WK, Shin JH, et al. High reliability and accuracy of dynamic magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of cervical Spondylotic myelopathy: a multicenter study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1107. Published 2022 Dec 20. doi:10.1186/s12891-022-06097-9

- Lavelle WF, Bell GR. Cervical myelopathy: History and physical examination. Semin Spine Surg. 2007;19(1):6-11. doi:10.1053/j.semss.2006.11.004

- Karadimas SK, Erwin WM, Ely CG, Dettori JR, Fehlings MG. Pathophysiology and natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(22 Suppl 1):S21-S36. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a7f2c3

- Costa F, Anania CD, Agrillo U, et al. Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: From the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) to the Italian Neurosurgical Society (SINch) Recommendations. Neurospine. 2023;20(2):415-429. doi:10.14245/ns.2244996.498