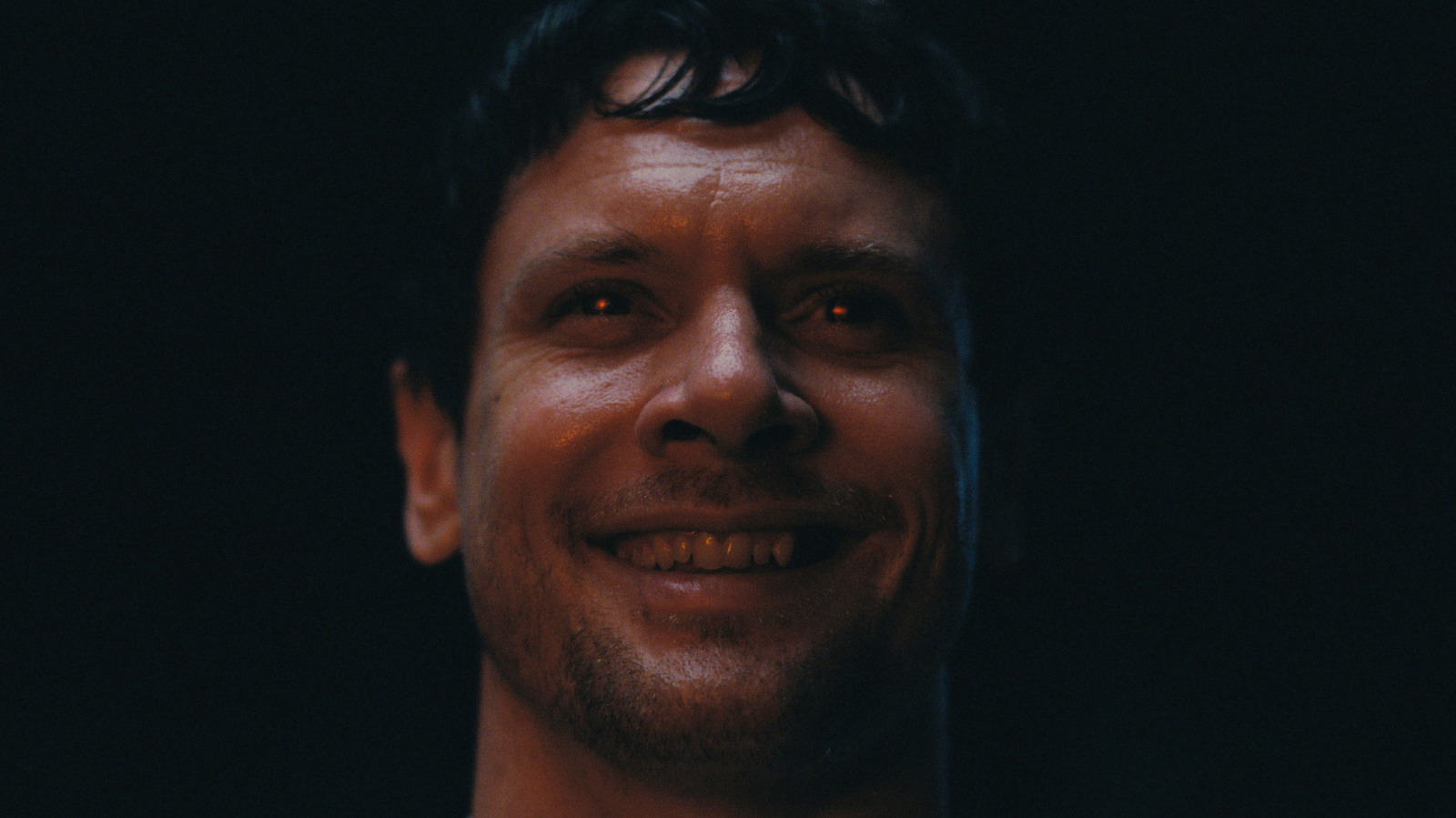

“As a culture, we’re not supposed to tell stories. We’re not supposed to make movies,” says Navy SEAL turned filmmaker Ray Mendoza when asked about portraying combat onscreen. But for his new film, Warfare, Mendoza and co-director Alex Garland recreated a personal story from Mendoza’s military time onscreen.

Warfare (out now via A24) is a retelling of a day during the Battle of Ramadi in the Iraq War that saw Mendoza’s platoon attempt to evacuate two members of their team after they were severely wounded in an IED explosion. The film is told in real-time, a stripped-down moment-by-moment rendering with minimal filmmaking flourishes.

“All the departments [on set] have a very similar structure to the military,” says Mendoza. “[It’s] multiple departments, working in concert with each other, to achieve one objective or vision.” After appearing on screen in Act of Valor, the 2012 film that used active duty SEALs as actors, Mendoza began a career as a military and technical advisor on Hollywood productions that ranged from Mark Wahlberg movie Lone Survivor to the Amazon series The Terminal List. Mendoza first met Garland while working on Civil War, the director’s dystopic drama that takes place during a second American civil war. Garland, impressed with Mendoza’s inherent filmmaking ability, approached him about making his feature debut on a reconstruction of a roughly movie-length story from his own life as a SEAL.

Mendoza and Garland talk to The Hollywood Reporter about the intention and portraying real-life combat onscreen.

How did you two come together?

ALEX GARLAND We met in pre-production on Civil War. Very quickly, Ray was making suggestions that were super helpful and made the film better. On set, I got to see Ray work with actors, which was interesting to watch the way they responded to him and the way he spoke to them. I could see him in effect, directing. Then, in post-production, I was cutting together a particular sequence in the White House towards the end of the film that Ray choreographed expertly. I was seeing things within it that I felt were surprising and interesting — textual details, rhythm and authenticity — and I contacted Ray and said, “‘”Do you want to make a film together, a 90 to 100 minutes forensic reconstruction of a real event that you know?”

Why was a forensic reconstruction as a film something you were interested in?

GARLAND I’ve been working in film for a long time. I was aware that fiction stories can be very good at talking about true things, but also wondering what the role of non-fiction was within film. It exists a lot in literature. You go into a bookshop and get lots of first-hand accounts, but film has a really complex relationship with non-fiction, and actually with just war in general. I think it’s because a book can be written for free, while film involves millions of dollars, sometimes 10s, and sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars. There’s pressures that get in the way of pure authenticity because sometimes things need to be amped up in order to get a return on the investment. That’s an overly simplistic way of saying it, but it’s sort of true. This was an exercise. If you take this [real-life event] and you work against that instinct, what does it produce? It’s an act of faith. In another way, it’s not an act of faith, because if you or anybody else were to sit down with Ray, and he was to open up and tell you in the straightforward, honest way that Ray speaks about something real that he had encountered, I guarantee you would be transfixed.

Ray, what was the driving force behind telling this specific story?

RAY MENDOZA Elliot [Miller, the SEAL severely wounded during the events seen in Warfare], the guy that Cosmo Jarvis plays, when he woke up had lots of questions. Big questions like “Why?” and “‘”What happened?” Later on, as he started getting more curious, questions like “What color were things?” No matter how many maps we drew and how many times we wrote it out, I think it’s made it more confusing because he lacks that core memory. When I first started in the movie industry, I was like, “Man, maybe one day I could do a recreation for him.” I thought I’d just save enough money and do a 30-minute recreation for him. I had pitched it a few times to see what the feedback would be. But, as expected, they wanted to change stuff. I wasn’t going to compromise from keeping it honest and true, because it was going to be the memory that was going to be given [to Elliot]. I didn’t want him to have a lie in his head.

As a veteran and former Navy SEAL, how do you feel about how Hollywood has portrayed combat onscreen?

MENDOZA Some of them do a really good job. I think they have a target audience, and I understand that the veteran and military community is the smaller percentage of the masses. So, for me, [I do not] expect a director to cater towards a smaller percentage. There are messages they want to convey, and some of it’s good, but it doesn’t get all the way across the goal line, though it is entertaining. I wouldn’t use, a lot of war movies, as an example, for me to be like, “Hey, my loved one, watch this scene. That’s how I felt.” Nobody’s gonna do that with those movies. I am not gonna use it as a way to bridge the gap for people to understand what war is like. It may be an entertaining story and a good movie, and it feels heroic and someone’s gonna want to join the military — I think it does a great job of doing that. But it’s not an accurate portrayal of what combat is.

What did the writing process look like?

MENDOZA [Writing] was probably more like a therapy session, to be honest. Obviously, it was very factual, and he had a lot of questions. And if [directing] doesn’t work out, he should be a therapist because of his ability to listen. I received more validation that way than I have with the 20 therapists that I’ve seen over 20 years. It’s just right over their head, and that’s frustrating. I was fearful [thinking], “What if he doesn’t understand or get it? This could be a very frustrating and painful process.” It was a relief to feel heard and understood, and then that being conveyed on paper.

How did casting work on a project like this?

GARLAND We had a prerequisite, which was that we had to accurately represent the age of people. We had a very, very tight shooting schedule, five weeks, and it would be physically demanding, not just in terms of carrying heavy bits of equipment — a machine gun is a really heavy bit of equipment — but also maintaining energy over a long day and then doing it again the next day. In the end, we also needed an experience component. The shooting schedule did not allow for long conversations about motivation on set. It had to be people who were kind of in control of their craft.

MENDOZA Alex did most of the talking. I had a few questions here and there, but I just like to watch and observe. I can, for the most part, have a good idea of what someone’s going to be willing to do. I just needed to know how far I was going to be able to push each guy and their willingness to do that, because they were going to represent my friends.

What has been the reaction from the people in your platoon?

MENDOZA Elliot was extremely grateful. It was a gift we all gave him. He has two kids who are asking questions now, and he can’t speak, and I think this is a great visual medium to explain what happened to their dad. I asked each guy, “Hey, man, how do you feel about how you were represented? How do you feel?” They were just like, “That’s as close as we’re gonna get it.”

About The Author

Discover more from imd369

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.