When the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) released the

latest findings from its nationwide India Diabetes (ICMR-INDIAB) survey,

the results painted a sobering picture of how India eats and why the

country is witnessing a surge in diabetes, obesity, and metabolic

disorders.

The study, which analysed, the diets of over 18,000 adults across all regions of India, found that

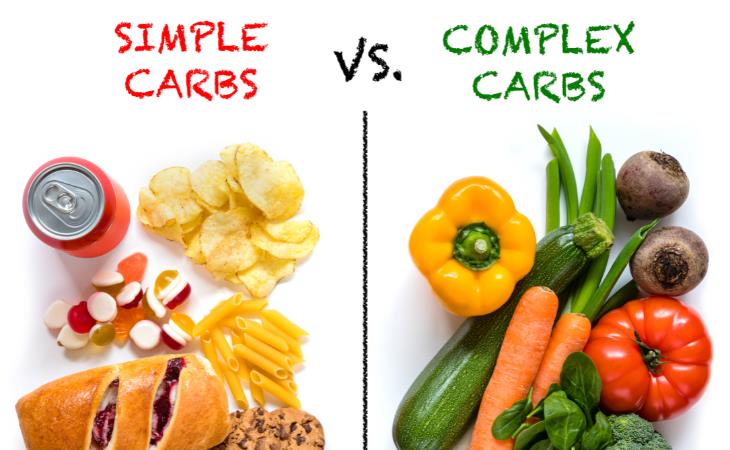

more than 62% of daily calories in the average Indian diet come from

low-quality carbohydrates such as white rice, milled wheat, and added

sugars.

Combined with high saturated fat intake and low protein consumption,

this dietary imbalance has become a potent recipe for disease.

Those with the highest carbohydrate consumption were found to have a

30% higher risk of developing newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, 20%

higher risk of prediabetes, and a 22% higher risk of general obesity

compared to those consuming the least carbohydrates.

But the most

striking finding is this: even replacing white rice with whole wheat or

millet flours did not lower the risk of diabetes or abdominal obesity.

What

researchers want to stress is that reducing total carbohydrate

quantity, not merely switching grains, is what really matters.

KEY HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE ICMR-INDIAB DIETARY STUDY

- 62.3% of total energy in Indian diets comes from low-quality carbohydrates (refined cereals and sugars).

- High-carb diets increase risk of type 2 diabetes by up to 30%, prediabetes by 20%, and obesity by 22%.

- Replacing refined carbs with milled whole grains (wheat or millet flour) offered no benefit.

- Substituting

5% of carb calories with protein (from dairy, pulses, eggs, or fish)

significantly reduced diabetes and prediabetes risk. - Protein

intake in India is low — only 12% of total energy — with most coming

from plant sources, and very little from dairy or animal protein.

‘REDUCE TOTAL CARBS, NOT JUST CHANGE THE GRAIN’

“Two big messages emerge from this study,” Dr. Sudha Vasudevan,

Senior Scientist and Head of the Department of Foods, Nutrition and

Dietetics Research at the Madras Diabetes Research Foundation tells

IndiaToday.in. “First, irrespective of the grain type, total

carbohydrates need to reduce. Second, replacing white rice with milled

whole grains like wheat or millet flour offers no benefit.”

The

reason, she explains, lies in the food matrix. “Whole grains must be

consumed intact. Once they are milled into fine flours, their glycemic

index increases, making the body’s response similar to that of refined

white rice. Milling breaks down the grain structure, causing blood sugar

to spike faster,” she adds.

This insight challenges the long-held assumption that switching from

polished rice to “whole wheat” automatically improves diet quality.

In

India, most “whole grains” are consumed as finely milled atta or ragi

flour not as intact grains like brown rice or whole millets, reducing

their health advantage.

THE PROTEIN GAP: INDIA NEEDS TO REBALANCE ITS PLATE

The study highlights that protein intake across India remains low,

averaging only 12% of daily calories, well below the global

recommendation of 15–20%. Most of this comes from plant sources, with

minimal intake of dairy, eggs, and fish.

Dr. R.M. Anjana, Managing

Director of Dr. Mohan’s Diabetes Specialities Centre and President of

the Madras Diabetes Research Foundation and lead author of the study,

says that a small but strategic dietary tweak can have a significant

impact on metabolic health.

“Replacing carbohydrate calories with

protein calories doesn’t mean eating red meat. It means increasing

plant, dairy, egg, and fish proteins, all of which are rich in

micronutrients and dietary fibre, and have lower glycemic indices,” she

explains.

The isocaloric substitution modelling in the study, which showed that

replacing just 5% of carb calories with protein reduced diabetes and

prediabetes risk, demonstrates that even small changes in dietary

composition can lead to measurable benefits.

“Foods like pulses, legumes, and dairy help lower the overall

glycemic load of meals. They also increase satiety, which means people

eat less frequently and are less prone to overeating refined foods,” Dr.

Anjana tells IndiaToday.in.

DESIGNING A HEALTHIER INDIAN PLATE

The ICMR findings call for a rethinking of what an “ideal Indian meal” should look like.

“The goal is not to eliminate staples but to rebalance the plate,” says Dr. Vasudevan.

For

instance, if a South Indian plate typically has four idlis, reduce it

to three and add one more bowl of sambar or dhal. For a North Indian

meal with two aloo parathas, cut down to one and increase the portions

of curd and dal fry, she says.

This principle: reducing cereal

portion size while increasing protein-rich accompaniments can be applied

to most traditional diets across regions without changing their

cultural essence.

“Every region’s plate, whether rice-based in the

South or wheat-based in the North, can follow this model: fewer refined

carbohydrates, and more pulses, legumes, milk, eggs, or fish,” she

notes.

A ONE-INDIA FOOD STRATEGY WITH REGIONAL SENSITIVITY

India’s diverse culinary map makes any “national food plate” a challenge. However, the nutritional problem is surprisingly uniform.

“Whether it’s rice, wheat, or millets, all are high in carbohydrates,” says Dr. Vasudevan. “So the big picture message is the same — reduce cereal quantity and increase protein foods. All regions can benefit from this guidance.”

Still, regional adaptations matter. Northeastern states, for example, have the highest protein intakes (up to 13.6% of energy, mostly from fish and red meat), while northern and eastern states rely more heavily on dairy or plant protein.

A national dietary framework, therefore, should retain cultural diversity while promoting common nutritional goals: fewer carbohydrates, moderate fat, and more protein.

THE AFFORDABILITY AND ACCESS CHALLENGE

Shifting diets, however, cannot be achieved without addressing the economic and food-access barriers. Pulses and dairy products, though nutritionally beneficial, are not equally affordable or available across states.

“Affordability plays a big role in food choices,” says Dr. Anjana. “That’s why the study does not suggest an overhaul of diets but small, feasible tweaks — such as reducing cereal portions and increasing protein foods like pulses and dairy.”

She emphasizes that policy-level support is critical. “Public

distribution systems could subsidize pulses and healthier oils instead

of only low-quality carbohydrates like white rice. This would help both

urban and rural populations make healthier choices without increasing

their food budget,” she suggests.

AVOIDING UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

One

concern with encouraging protein substitution is whether it might

inadvertently increase saturated fat intake, particularly from dairy, or

create cost or environmental pressures.

Dr. Vasudevan addresses

this directly: “The study recommends moderation. The focus is on plant

and low-fat dairy proteins, not red meat or full-fat dairy. Pulses and

legumes, for example, are both cost-effective and environmentally

sustainable sources of protein.”

India’s policy framework, she

says, should promote “right nutrition investments” that align health,

affordability, and sustainability — a strategy that benefits both

individual health and national disease burden.

CHANGING HABITS, ONE PLATE AT A TIME

Despite

the data, the biggest challenge may be behavioural. Cutting down on

rice or rotis, deeply tied to comfort and culture, is easier said than

done.

“The plate will still contain our familiar foods,” says Dr.

Anjana reassuringly. “We’re not asking people to abandon cultural

dishes. The key is portion balance — slightly reducing cereal quantity

and proportionately increasing protein choices like dal, curd, eggs, or

fish.”

Higher protein meals, she adds, “keep you full longer, prevent blood

sugar spikes, and reduce frequent hunger — which refined carbs tend to

trigger.”

As India confronts a growing epidemic of lifestyle

diseases, the message from the study is clear: it’s not just what we

eat, but how much and how balanced our plates are.