Theodore Warkentin, a leading world expert on HIT, recently visited Vermont and delivered a talk on emerging concepts in HIT. During his talk, he lamented that it takes ten years for a new idea to make it into Harrison’s textbook of internal medicine. Within the next day, I read several of his articles, as well as newer HIT literature, and updated the IBCC section on HIT accordingly. Below are six pearls from this update.

[#1] HIT risk is 10 times higher with unfractionated heparin than with enoxaparin

- This isn’t anything particularly new, but it comes up repeatedly in reviews on HIT, and it’s worth emphasizing.

- Unfractionated heparin molecules are much longer than unfractionated heparin, so they are more likely to form immunogenic complexes with PF4 (platelet factor 4) that cause HIT.

- Enoxaparin is preferable to unfractionated heparin for DVT prophylaxis (if the GFR is >30 ml/min). Advantages of enoxaparin include a 10-fold lower risk of HIT, possibly greater efficacy, and fewer injections (which reduces patient discomfort & RN workload).

- 🙏 Please use enoxaparin for DVT prophylaxis when possible.

- In terms of therapeutic anticoagulation, there are many situations where therapeutic enoxaparin is preferable to an unfractionated heparin infusion (e.g., DVT/PE patients without risk factors for bleeding or the need for a procedure).

- The selection between unfractionated heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin is discussed here.

[#2] Risk stratification with the HEP score

- The primary risk-stratification tool for HIT is the 4T score. The 4T score is a pretty good tool. It’s well-validated. It has nicely well-defined post-test probabilities of having HIT. In short, the 4T score isn’t going to be replaced by the HEP score (nor, in my opinion, should it).

- The 4T score can be difficult to apply. In the IBCC, there is a section that walks you through calculating the 4T score with useful pointers.

- Recently, the HEP score was validated and shown in one study to outperform the 4T score among critically ill patients. (30463915) The recently published British Society of Hematology guidelines indicate that the 4T score or HEP score may be used. (38153164) So the HEP score is now validated and guideline-recommended.

- Where does the HEP score fit into risk stratification for HIT? I think we should still start with a 4T score.

- If the 4T score is 1-3, this basically excludes HITT.

- If the 4T score is 6-8, there is a substantial risk of HITT (~50%).

- If the 4T score is 4-5, this is ambiguous (~10% risk of HITT). Applying the HEP score as a tie-breaker might be reasonable.

- We’ll likely hear more about the HEP score over time to determine exactly how it should be used.

- MDCalc has a nice HEP score calculator (although it still hasn’t incorporated newer evidence supporting the HEP score).

[#3] What to do with an intermediate 4T score in a patient without thrombosis??

- Perhaps the most common conundrum regarding HIT in the ICU is how to manage a patient with an intermediate 4T score (4-5) who doesn’t have clinical signs of thrombosis.

- Guidelines generally recommend empiric anticoagulation with a non-heparin anticoagulant while awaiting HIT test results. However, only ~10% of patients with a 4T score of 4-5 will actually have HIT. For the remaining 90% of patients who don’t have HIT, placing them on anticoagulation may cause needless hemorrhages (especially since they’re already thrombocytopenic!).

- I asked Dr. Warkentin about this conundrum, and he agreed that it’s a problem. He suggested that in many cases, more careful assessment of the 4T score in patients without thrombosis would show that the score is actually 1-3 (and not 4-5).

- My current thoughts on this situation are listed below. I would be interested in hearing from others about their approaches.

- [1] Carefully consider the risk of HIT. Consider both the 4T score and the HEP score (discussed above).

- [2] Carefully consider the bleeding risk (risk assessment & scoring is discussed here).

- [3] Consider the D-dimer level. In HIT, the D-dimer level is usually dramatically elevated (e.g., >2000-4000 FEU or >1000-2000 DDU). (14961154, 40358013) If the patient’s D-dimer level is dramatically elevated, this supports the presence of HIT and/or DIC, which makes anticoagulation more reasonable. Alternatively, if the D-dimer level isn’t markedly elevated, this may cast some doubt on the diagnosis of HIT.

- [4] Thromboelastography might be theoretically helpful in this context because HIT appears to be associated with a hypercoagulable pattern, whereas a hypocoagulable pattern may argue against HIT and potentially signal an increased risk from anticoagulation. (18056152, 17632008) However, evidence regarding thromboelastography in HIT is scarce.

[#4] Choice of non-heparin anticoagulant

- Dr. Warkentin is a critic of the use of direct thrombin inhibitors (e.g., argatroban) for several reasons:

- Evidence used to obtain FDA approval for arbatroban was weak (based on historical control data).

- Titration of argatroban infusions based on PTT is fraught with hazards (there are numerous causes of PTT elevation, such as DIC, which can make it seem like the patient is anticoagulated when in fact they are not).

- Inhibition of thrombin may reduce protein C activation, potentially promoting thrombosis. (37959386)

- Dr. Warkentin is a proponent of Xa inhibitors (fondaparinux or apixaban). These agents have the advantages of more reliable pharmacokinetics, which allows for more reliable anticoagulant efficacy. The main drawback is that both agents have a long half-life, which can be problematic if bleeding occurs or a procedure is required.

- ASH guidelines make no recommendation about which anticoagulant to use; they just list all the non-heparin anticoagulants alphabetically. This might make it seem like argatroban is the best, but it simply starts with the letter A.

[#5] Autoimmune HIT

- Over the last several years, several HIT-like disorders have been unearthed (figure above).

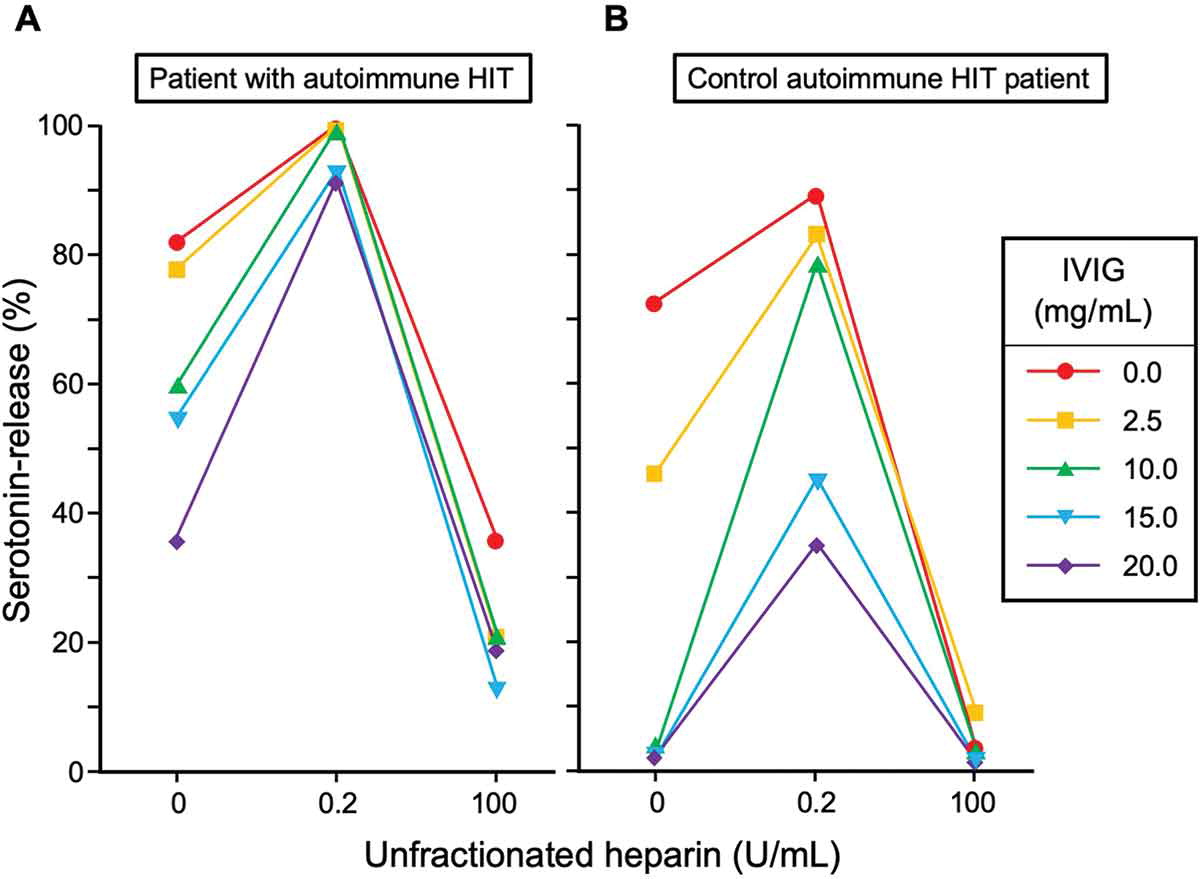

- From a practical standpoint, the most important of these is autoimmune HIT (most of the others are very rare). Autoimmune HIT is similar to classic HIT, except that the antibody is able to stimulate platelet activation in the absence of heparin (figure below). Heparin independence means that hypercoagulation will persist after heparin has been discontinued.

- Autoimmune HIT is notable for being more severe and harder to treat than classic HIT. Autoimmune HIT often causes overt DIC (with platelets <20,000), which can make the diagnosis of HIT a bit harder.

- (Further discussion of the diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune HIT is here).

[#6] IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin)

- IVIG can compete with HIT antibodies, blocking their ability to bind to Fc-receptors on platelets.

- IVIG blocks thrombosis stimulated by HIT antibodies both in vitro and also ex vivo (if a patient with HIT is given IVIG, their plasma loses its ability to stimulate platelets in a serotonin-release assay).

- There are no RCTs on this (largely impossible given the disease’s rarity), but accumulating case reports and expert opinion indicate that IVIG is a useful and highly effective therapy for HIT.

- Indications for IVIG are currently unclear, but might include the following:

- Inability to give anticoagulant (e.g., due to hemorrhage).

- Suspected autoimmune HIT (e.g., unusually severe, persistent HIT).

- Failure of other therapies (e.g., persistently low platelets and persistently elevated D-dimer despite heparin discontinuation and use of a non-heparin anticoagulant). (28622439, 39644042, 38153164, 31274032)

Bonus: research that sorely needs to be done (could someone please do this?)

- HIT appears to induce a hypercoagulable pattern on thromboelastography (TEG); however, limited research has been conducted on this topic. (e.g., 17632008)

- TEG is widely available and may be performed rapidly. Theoretically, this could be utilized as a rapid screening test for HIT.

- Heparinase and exogenous heparin are widely available laboratory reagents. A series of three TEG reactions could be utilized to screen for HIT:

- #1: TEG (aka “native TEG” performed without altering the patient’s blood).

- #2: Heparinase TEG (TEG after the addition of heparinase, which removes any exogenous/endogenous heparins).

- #3: TEG performed on blood after the addition of 0.2 U/ml heparin.

- Theoretically, HIT could be revealed by paradoxical reactions to heparin in this series of TEG reactions (e.g., removal of heparin decreases coagulability, or the addition of exogenous heparin increases coagulability).

That’s all for now. More information:

- IBCC chapter on HIT

- Key review articles by Dr. Warkentin (all open-access):

Latest posts by Josh Farkas (see all)