September 03, 2025

5 min read

Key takeaways:

- Medical and long-term care will cost U.S. residents $232 billion in 2025.

- Informal care by family and other partners costs $233 billion.

- Loss in quality of life for caregivers costs $6 billion.

When patients are diagnosed with dementia, medical costs increase by thousands of dollars, while families lose thousands as they shift to caregiving, according to a panel discussion at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“We want to improve understanding of who bears the cost,” Julie M. Zissimopoulos, PhD, co-director of the aging and cognition program, Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, University of Southern California, said during the presentation.

Data were derived from Zissimopoulos J, et al. U.S. cost of dementia. Presented at Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. July 27-31, 2025. Toronto.

The Alzheimer’s Association and USC Schaeffer partnered to develop the U.S. Cost of Dementia Model, which estimates $781 billion in total costs for dementia in the United States in 2025.

Julie M. Zissimopoulos

These costs include $232 billion (30%) for medical and long-term care, $233 billion for the care provided by family and friends (30%), $8 billion (1%) in the forgone earnings of care partners, and $6 billion in loss of quality of life (1%) for these partners.

“A large part of the project is to increase the infrastructure to support research capacity for addressing these costs,” Zissimopoulos said.

Costs around diagnosis

The U.S. Cost of Dementia Model specifically examined costs due to dementia, including hospitalization, during the year of diagnosis.

“In general, people with dementia are sicker and older and thus have higher medical expenses,” Johanna Thunell, PhD, research scientist, USC Schaeffer Center, said during the panel discussion.

Medical costs begin increasing for patients with Alzheimer’s in the months leading up to their diagnosis and remain higher afterward, with approximately 50% of their Medicare costs due to hospitalizations.

However, Thunell said, these costs may be due to a variety of reasons beyond AD, which may have been diagnosed during these hospitalizations.

Johanna Thunell

Researchers used a sample of Medicare Fee for Service claims for 43,781 patients diagnosed with dementia during an inpatient visit in 2017 and compared them with claims for 1,697,723 patients with inpatient visits but no dementia.

“We used models that control for demographics and a broad set of comorbid conditions,” Thunell said, noting that 70% of the top primary discharge diagnoses such as sepsis, acute kidney failure and pneumonia were the same for both groups.

“This overlap indicates that persons with dementia are not necessarily going into the hospital with vastly different medical concerns, and they’re not dementia-specific,” she said.

Annual medical costs for hospitalized patients with dementia were $37,463 higher than the annual medical costs for those who were hospitalized without dementia. When adjusted for demographics, this difference increased to $38,208.

“But it’s essentially the same,” Thunell said.

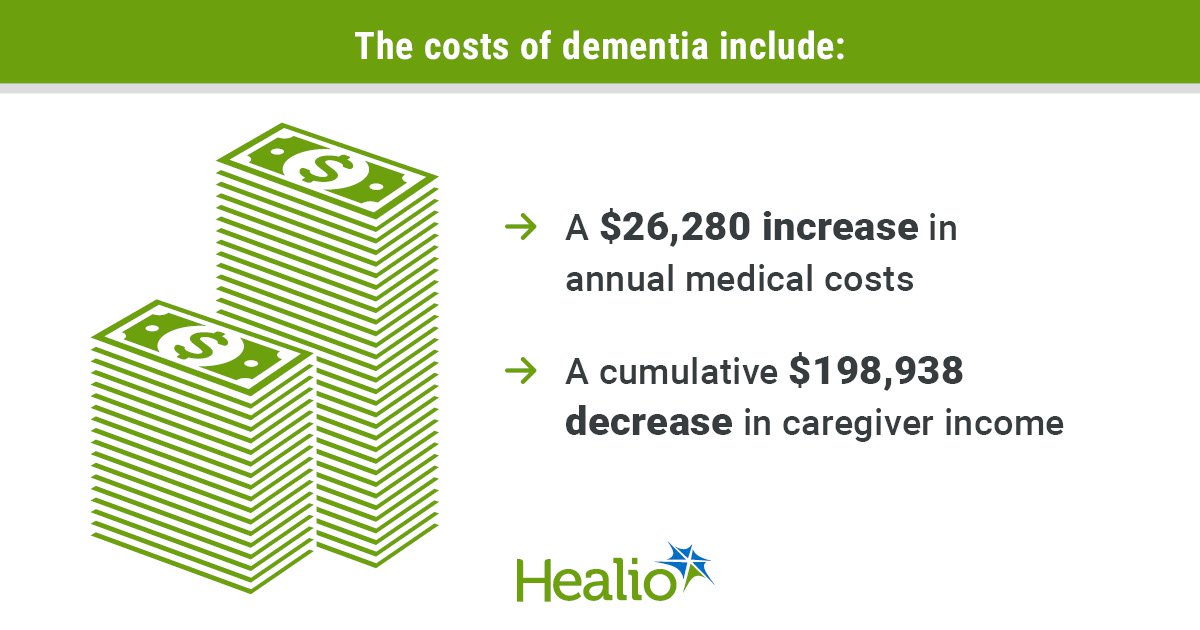

When adjusted by the presence of 30 comorbidities, the difference was $28,296. Adjustment for fixed effects decreased the difference to $26,280.

Thunell said there are several possible explanations for these differences, such as longer hospital stays for patients with dementia due to uncertainty over where they should be discharged to, while patients who do not have dementia may have a plan in place.

“They may have complications associated with mismanaged chronic conditions that lead to longer stays or delayed treatment,” Thunell said. “Perhaps additional testing is being conducted in order to get that dementia diagnosis.”

Timely diagnosis in primary care or outpatient settings could mitigate these costs, she continued, as teams identify care partners and promote care planning.

“Where does this person go when they get discharged? Who’s going to take care of them?” she said. “Who’s going to help take care of them when they’re in the hospital and their loved ones are not able to care for them? Who’s going to advocate for them?”

This planning would ensure better care for chronic conditions as well, she said.

“If we know a person has diabetes, and we know that they have dementia, we are going to be able to help them manage the diabetes and perhaps prevent these hospitalizations or prevent costlier versions of these hospitalizations,” Thunell said.

Post-acute care remains higher as well, she said.

“They maybe have longer skilled nursing,” Thunell said. “Maybe they’re paying for home health. They have caregiver needs. These are all going to feed into costs that we’re not necessarily going to measure in Medicare claims data.”

The next step is to consider the drivers behind these spikes in costs during the year that dementia is diagnosed.

“There’s much more work to do,” she said.

Costs for caregivers

“As the prevalence of dementia grows, more and more families are stepping into the caregiver role,” Mandy Manying Cui, a first-year PhD student at USC Schaeffer, said during the presentation.

The U.S. Cost of Dementia Model estimated that 6 million dementia caregivers in the United States provide 31 weekly hours of care, compared with 14 hours for caregivers of patients without dementia.

“Being a dementia caregiver is not only physically and emotionally demanding, but it also involves a significant time commitment,” she said.

Mandy Manying Cui

As caregiving hours have decreased over the past decade for other diseases, caregiving hours for dementia have increased by approximately 45%, she said. Also, 62% of dementia caregivers have served in these roles for 4 or more years, compared with 38% of caregivers for other diseases. In 2025, dementia caregivers will provide 6.8 billion hours of care, valued at $233 billion, she added.

“More than half of this unpaid care is shouldered by middled-aged adults,” Cui said. “The levels of commitments required to care for loved ones with dementia often come with great tradeoffs, especially financial ones. Many families lose income streams.”

Percentages of caregivers who reduce their work include 27% of dementia caregivers and 18% of non-dementia caregivers. Also, 40% leave the workforce permanently after exiting temporarily, with 20% returning for part-time hours or less.

These disruptions lead to long-term financial insecurity, Cui said.

“And given that dementia is a progressive disease, caregiving demands only intensify over time as the symptoms worsen,” she said.

The U.S. Cost of Dementia Model based a simulation on adults aged 51 to 55 years with at least one living parent or parent-in-law, representing approximately 18 million adults in the United States who mostly work full-time with an average income of $89,433. This model estimated 20% to have a parent with dementia (mean age = 75.8 years).

Adults with a parent with dementia would spend 8.07 years providing care and 9.4 years working, including 7.11 years of full-time work, earning $541,549. Adults who would not need to care for a parent with dementia would work for 11.43 years, including 7.86 years full-time, earning $740,487.

“Dementia caregivers on average lose about $198,938 in cumulative earnings,” Cui said.

These findings indicate why policies that reduce the economic tolls on caregivers are necessary, she continued, in addition to showing how this modeling could be used to answer research questions and produce nationally representative estimates.

“Building on our current models and our future research will continue to quantify other important aspects of dementia caregiving, such as Social Security benefits,” Cui said. “We can help to advocate for futures where dementia caregiving burdens are better quantified and understood and dementia caregivers are better supported.”

References:

- Cui MM. Long-term economic impact of dementia caregiving. Presented at Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. July 27-31, 2025. Toronto.

- Neumann LTV. Voices from the community: New insights into the costs of dementia from persons with lived experience, public health leaders, and health care providers. Presented at Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. July 27-31, 2025. Toronto.

For more information:

Mandy Manying Cui can be reached at manying@usc.edu. Johanna Thunell, PhD, can be reached at jthunell@usc.edu.