August 26, 2025

5 min read

Key takeaways:

- Genetic testing can be accomplished for most patients with gastrointestinal cancer prior to starting chemotherapy.

- Patients with genetic variants have fewer hospitalizations with reduced dosage.

Genetic testing prior to starting standard chemotherapy for gastrointestinal cancer could substantially reduce toxicities for patients with drug-gene interactions.

A prospective investigation found health care providers could get most screening results prior to initiating treatment, and patients who have variants in dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPYD) or UDP glucuronosyltransferase family 1 member A1 (UGT1A1) genes could avoid hospitalizations or ED visits.

Data were derived from Tuteja S, et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2025;doi:10.1200/PO-25-00086.

Sony Tuteja

“Start testing now,” Sony Tuteja, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FAHA, FCCP, director of pharmacogenomics in the Penn Medicine Center for Genomic Medicine and research assistant professor of translational medicine and human genetics at University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, told Healio.

“We know that there are at least six to eight variants that have high impact. If you don’t test, you’re essentially giving an overdose to your patients [with these variants], and this is totally preventable.”

‘Don’t need to do it’

Gastrointestinal malignancies such as colorectal cancer and pancreatic cancer are commonly treated with fluoropyrimidine antimetabolites and/or irinotecan, according to study background.

However, patients with DPYD or UGT1A1 variants can experience serious adverse events related to these treatments.

In 2018, researchers published results of a study in The Lancet Oncology that included more than 1,100 individuals and found those with DPYD variants had a significantly greater risk for “severe toxicity” to fluoropyrimidines than those without the variant (39% vs. 23%; P = .0013).

Studies also have shown dose reductions could limit those toxicities, which prompted the European Medicines Agency to begin recommending DPYD testing in 2020.

The European Society of Medical Oncology also added it to its guidelines.

“This didn’t really happen in the U.S. until recently,” Tuteja said. “We did a qualitative study initially to understand what the barriers were to do this in the U.S. We interviewed 25 oncology specialists at Penn, both oncologists and oncology pharmacists, and the No. 1 thing they said was NCCN does not endorse this. It’s not in the guidelines, so we don’t need to do it.

“It was not until February 2025 that NCCN updated its gastrointestinal cancer guidelines to say you should consider it,” she added. “They don’t say you must do it.”

Oncologists also told Tuteja and colleagues that testing would take too long, results would be difficult to locate in the electronic health record and there would be low prevalence of variants.

Their responses prompted Penn to address these issues and investigate the feasibility of testing.

Practice changes

Tuteja and colleagues spent a year and a half creating infrastructure for screening.

First, they looked at testing time.

“[Originally], we were sending our results to a third-party vendor in Salt Lake City. It took 3 or 4 weeks to come back, and that’s not acceptable in clinical care,” Tuteja said. “We worked with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia to create a test that could be returned in 7 to 10 days.”

They included more variants, as well.

“This test we were sending back in 2019 had only three variants and those only found in patients of European ancestry,” Tuteja said. “We don’t want to widen the health disparities by not checking all the variants that are relevant.”

They also worked with IT to modify the EHR so genetic test results would be housed in a special precision medicine tab.

“Then we created a clinical decision support alert so that when a patient had a variant that was important, and [the clinician] went to prescribe the medication, they would get an alert that said this patient is an intermediate metabolizer and perform a 50% dose reduction for these drugs,” Tuteja said.

Lastly, researchers focused on education.

“Maybe one of the variants is very rare, but if you take the eight to 10 that are clinically actionable, 5% to 8% of the population will have one of those, so it’s not as rare as you’d think,” Tuteja said. “I think the clinicians were not aware of all this information.”

After that, researchers prospectively screened 225 patients with gastrointestinal cancer (mean age, 60.7 years; standard deviation, 12.2; 54% men; 74% white) for DPYD and UGT1A1 variants, and compared that data with 229 samples (mean age, 59.4 years; standard deviation, 11.9; 53% men; 80% white) from a biobank cohort that did not undergo testing.

The number of results received prior to start of chemotherapy served as the primary endpoint. Toxicity causing hospitalization or ED visits served as a secondary endpoint.

‘Testing has dramatically improved’

The median turnaround time for screening results was 10 days (interquartile range, 9-13).

In all, 57.4% of patients had results before beginning chemotherapy.

Urban sites had significantly faster turnaround time than suburban ones (10 days vs. 13 days, P < .01).

Tuteja said results likely can be obtained quicker today than at the time of the study.

“Now, they’re returning results in 5 to 10 days,” she said. “Even if your own institution doesn’t have a molecular testing lab, you can find a commercial vendor that can do this rapidly with a test that has all the important variants. Access to testing has dramatically improved.”

In the prospective cohort, eight of 11 patients with a DPYD variant received fluoropyrimidine, and eight of 39 UGT1A1 poor metabolizers were treated with irinotecan.

Of those 16 patients with a drug-gene interaction, 69% had results prior to chemotherapy and all of them received recommended dose reductions.

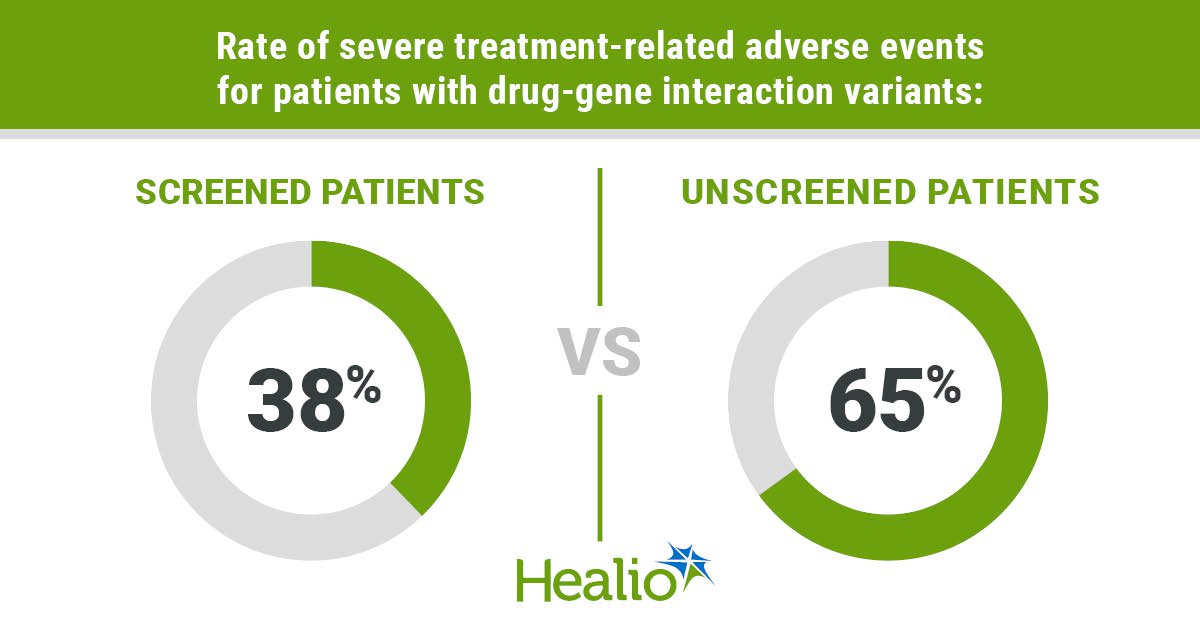

Compared with biobank samples, patients in the prospective cohort with a drug-gene interaction had a numerically lower rate of severe treatment-related adverse events (38% vs. 65%) and treatment discontinuation (31% vs. 47%), as well as significantly lower rate of treatment modifications (38% vs. 76%, P = .028).

“We weren’t powered to show a significant reduction in events,” Tuteja said. “If we had tested more patients, we probably would have seen a significant difference.”

Researchers acknowledged study limitations, including lack of data on toxicity grades, and clinicians not waiting for screening results before starting chemotherapy.

Best drugs, best doses

Anil Kapoor, MD, was diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer in January 2023.

Kapoor, a urologist and head of transplants at St. Joseph’s Healthcare in Ontario, received DPYD and UGT1A1 testing and the results came back negative.

He died a month later due to adverse events from treatment with 5-FU.

“He ended up having another variant that is not common in European populations,” Tuteja said. “He was of South Asian descent.”

Cases like Kapoor’s highlight the need for more research into other potential variants, particularly those that might impact individuals who do not identify as white.

“This is a very large gene,” Tuteja said. “There are over a thousand variants already known. Some of them don’t have any impact on the gene function, and some of them have a dramatic impact.”

This should not stop the use of current testing, though.

“Don’t let perfect be the enemy of the good,” Tuteja said. “Let’s take what we know and test those variants. As more things are uncovered, then we can look into that.”

Tuteja emphasized that NCCN guidelines and FDA box warnings would have the greatest impact on testing uptake.

Going forward, Tuteja and colleagues plan to provide real-world data on tumor outcomes with reduced chemotherapy dosage to promote guideline changes.

Future research could transform care in the next decade — and not just regarding chemotherapy treatments.

“I think we’ll be sequencing, not this gene, but all genes related to drug response so that we can tailor medications,” Tuteja said. “If it’s a patient with cancer, it’ll be for their chemotherapy and also supportive care medications they get during treatment — pain medications and depression medications. I think we will be sequencing genes related to multiple medication classes so that patients get the best drugs and the best doses for them.”

References:

For more information:

Sony Tuteja, PharmD, MS, BCPS, FAHA, FCCP, can be reached at sony.tuteja@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.