August 20, 2025

2 min read

Key takeaways:

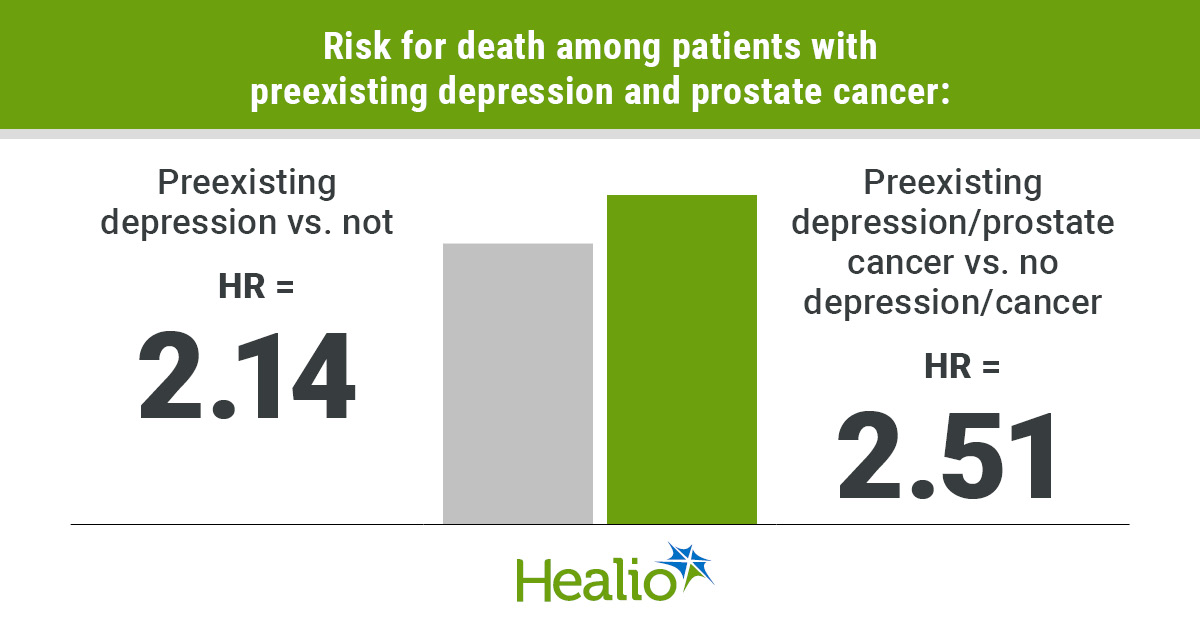

- Men who have depression before prostate cancer diagnosis may have significantly greater risk for death than those who do not.

- OS curves suggest long-term survival impact of preexisting depression.

Preexisting depression may have a significant impact on survival for men with prostate cancer.

A long-term cohort study found patients with preexisting depression had more than twice the risk for death as those without depression, and they had a mortality risk 2.5 times greater than individuals who did not have cancer or depression.

Data derived from Zhang L, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.23143.

Preexisting depression has a “role in exacerbating disease progression and worsening survival,” Lei Zhang, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Uniformed Services University, and colleagues wrote.

Conflicting data

More than 310,000 men are projected to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in the U.S. in 2025, making it the second most common malignancy in the country, according to American Cancer Society’s Cancer Statistics 2025 report.

Approximately one in six patients with prostate cancer also have “major depression.” That rate is roughly twice as high as that of the general population, according to study background.

“Studies suggest a bidirectional association between depression and prostate cancer,” researchers wrote. “Preexisting depression accelerates cancer progression. A prostate cancer diagnosis may also trigger new-onset depression due to psychological trauma and uncertainty about prognosis, which may reduce quality of life and survival through mechanisms such as dysregulated inflammatory responses, hormonal imbalances and impaired immune function.”

Studies investigating preexisting depression and survival for patients with prostate cancer have produced mixed results.

One showed men who had depression 2 years before their diagnosis had worse outcomes over a 4-year period, but another did not find any association.

Zhang and colleagues investigated using the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, which began enrollment in 1993 and had about 25 years of follow-up.

They included 38,169 participants, of whom 205 had prostate cancer and preexisting depression (mean age, 61 years; standard deviation, 5 years), 2,096 with just prostate cancer (mean age, 61 years; standard deviation, 5 years) and 35,868 control patients without cancer or preexisting depression (mean age, 61 years; standard deviation, 4 years).

OS served as the primary endpoint.

Significant increase

Among patients with prostate cancer, those who had preexisting depression had significantly worse OS than those who did not (HR = 2.14; 95% CI, 1.34-3.42).

Men with prostate cancer and preexisting depression also had significantly worse OS compared with those in the control group (HR = 2.51; 95% CI, 1.63-3.87).

Survival curves in both analyses began separating more than 20 years after trial enrollment, suggesting long-term impact.

“This finding should be interpreted cautiously due to the primary limitation of unmeasured confounding factors, such as treatment and disease severity,” researchers wrote. “Our findings may help physicians and patients better understand the role of depression in prostate cancer survival, supporting further studies to explore appropriate interventions for this population.”